|

|

Water

Detected on Dwarf Planet Ceres

This is an artist’s impression of the dwarf planet Ceres. Image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech. NASA Press Release Scientists

using the Herschel space

observatory have made the first

definitive detection of water

vapor on the largest and roundest

object in the asteroid belt, dwarf

planet Ceres.

"This is the first time water vapor has been unequivocally detected on Ceres or any other object in the asteroid belt and provides proof that Ceres has an icy surface and an atmosphere," said Michael Küppers of ESA in Spain, lead author of a paper in the journal Nature.  An

artist's concept of Ceres with

vaporous jets in the asteroid

belt. Courtesy NASA

Herschel is a European Space

Agency (ESA) mission with

important NASA contributions.

Data from the infrared

observatory suggest that

plumes of water vapor shoot up

from Ceres when portions of

its icy surface warm slightly.

The results come at the right time for NASA's Dawn mission, which is on its way to Ceres now after spending more than a year orbiting the large asteroid Vesta. Dawn is scheduled to arrive at Ceres in the spring of 2015, where it will take the closest look ever at its surface. "We've got a spacecraft on the way to Ceres, so we don't have to wait long before getting more context on this intriguing result, right from the source itself," said Carol Raymond, the deputy principal investigator for Dawn at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Dawn will map the geology and chemistry of the surface in high resolution, revealing the processes that drive the outgassing activity." For the last century, Ceres was known as the largest asteroid in our solar system. But in 2006, the International Astronomical Union, the governing organization responsible for naming planetary objects, reclassified Ceres as a dwarf planet because of its large size. It is roughly 590 miles (950 kilometers) in diameter. When it first was spotted in 1801, astronomers thought it was a planet orbiting between Mars and Jupiter. Later, other cosmic bodies with similar orbits were found, marking the discovery of our solar system's main belt of asteroids. Scientists believe Ceres contains rock in its interior with a thick mantle of ice that, if melted, would amount to more fresh water than is present on all of Earth. The materials making up Ceres likely date from the first few million years of our solar system's existence and accumulated before the planets formed.  Water

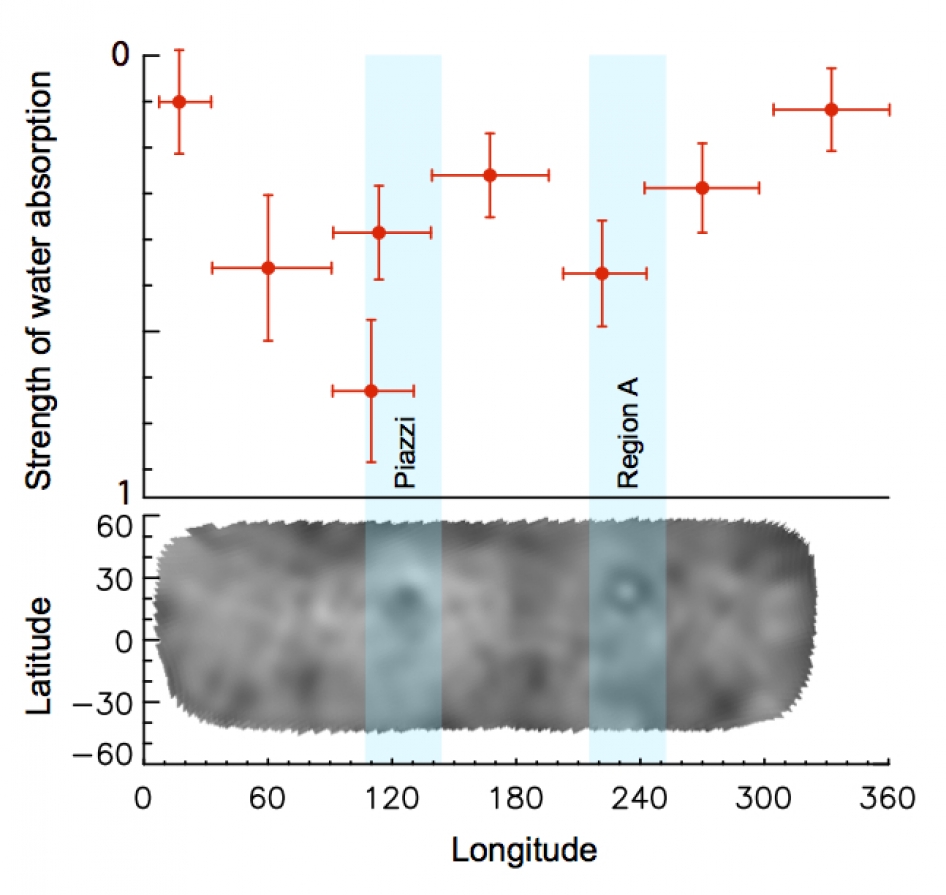

detection on Ceres

This graph shows variability in the intensity

of the water absorption signal detected at

Ceres by the Herschel space observatory on

March 6, 2013. The most intense readings

correspond to two dark regions on the surface

known as Piazzi and Region A, identified in

the ground-based image of Ceres by the W.M.

Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii. The two

data points at 110 degrees longitude were

taken in a time interval of about 9 hours --

equal to the Ceres rotation period -- showing

that variability in the water vapor production

is possible even over short periods.

Herschel is a European Space Agency mission, with science instruments provided by consortia of European institutes and with important participation by NASA. While the observatory stopped making science observations in April 2013, after running out of liquid coolant, as expected, scientists continue to analyze its data. NASA's Herschel Project Office is based at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. JPL contributed mission-enabling technology for two of Herschel's three science instruments. The NASA Herschel Science Center, part of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, supports the United States astronomical community. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. Image credit: Adapted from Küppers et al. Courtesy NASA Until

now, ice had been theorized to

exist on Ceres but had not been

detected conclusively. It took

Herschel's far-infrared vision to

see, finally, a clear spectral

signature of the water vapor. But

Herschel did not see water vapor

every time it looked. While the

telescope spied water vapor four

different times, on one occasion

there was no signature.

Here is what scientists think is happening: when Ceres swings through the part of its orbit that is closer to the sun, a portion of its icy surface becomes warm enough to cause water vapor to escape in plumes at a rate of about 6 kilograms (13 pounds) per second. When Ceres is in the colder part of its orbit, no water escapes. The strength of the signal also varied over hours, weeks and months, because of the water vapor plumes rotating in and out of Herschel's views as the object spun on its axis. This enabled the scientists to localize the source of water to two darker spots on the surface of Ceres, previously seen by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based telescopes. The dark spots might be more likely to outgas because dark material warms faster than light material. When the Dawn spacecraft arrives at Ceres, it will be able to investigate these features. Credits: Production editor: Dr. Tony Phillips | Credit: Science@NASA More information: This

research is part of the

Measurements of 11 Asteroids and

Comets Using Herschel (MACH-11)

program, which used Herschel to

look at small bodies that have

been or will be visited by

spacecraft, including the targets

of NASA's previous Deep Impact

mission and upcoming Origins

Spectral Interpretation Resource

Identification Security Regolith

Explorer (OSIRIS-Rex). Laurence O'

Rourke of the European Space

Agency is the principal

investigator of the MACH-11

program.

Herschel is a European Space Agency mission, with science instruments provided by consortia of European institutes and with important participation by NASA. While the observatory stopped making science observations in April 2013, after running out of liquid coolant, as expected, scientists continue to analyze its data. NASA's Herschel Project Office is based at JPL. JPL contributed mission-enabling technology for two of Herschel's three science instruments. The NASA Herschel Science Center, part of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, supports the U.S. astronomical community. Dawn's mission is managed by JPL for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Dawn is a project of the directorate's Discovery Program, managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Ala. UCLA is responsible for overall Dawn mission science. Orbital Sciences Corp. in Dulles, Va., designed and built the spacecraft. The German Aerospace Center, the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, the Italian Space Agency and the Italian National Astrophysical Institute are international partners on the mission team. Caltech manages JPL for NASA. More information about Herschel is online at: http://www.esa.int/SPECIALS/herschel. More information about NASA's role in Herschel is available at: http://www.nasa.gov/herschel. For more information about NASA's Dawn mission, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/dawn. |

|

Ceres:

Asteroid or Planet?

Credit:

NASA, ESA, J. Parker (SwRI) et al.

Explanation:

Is Ceres an asteroid or a planet? Although a

trivial designation to some, the recent suggestion

by the Planet Definition Committee of the

International Astronomical Union would have Ceres

reclassified from asteroid to planet. A change in

taxonomy might lead to more notoriety for the

frequently overlooked world. Ceres, at about 1000

kilometers across, is the largest object in the

main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Under

the newly proposed criteria, Ceres would qualify

as a planet because it is nearly spherical and

sufficiently distant from other planets. Pictured

above is the best picture yet of Ceres, taken by

the Hubble Space Telescope as part of a series of

exposures ending in 2004 January. Currently,

NASA's Dawn mission is scheduled to launch in 2007

June to explore Ceres and Vesta, regardless of

their future designations.

Those who took this image and who have studied it , according to their study believe that :"Although very dark, the asteroid has a relatively brighter area of unknown composition" (more from hubblesite.org and APOD). Look very carefully at this image above. For what you see is quite important.Why ? Because, as you can see above this black and white image of Ceres is very pixelated, and this produces a number of both scientific investigative, and image problems that could lead to giving a incorrect scientific analysis of whatever it is in space exploration that is under study. In this specific case also applying to the dwarf planet Ceres. Secondly, the image above is at the point to where the onset of loosing digital information is seriously already effecting the image. Again , the loss of any such information leads to not having enough informative scientific data to conclude what may or may not be the truth about Ceres. On top of this information from the above aforementioned agencies in so many words state that the image at this stage, does not give enough data to study it completely and appropriately. Note to what is specifically said about :"the brighter area" it is of an :"unknown composition". The larger image was approximately doubled in size to show that a good scientific analysis cannot be derived from such an image. the very fact that the smaller image above shows better resolution and clarity proves this point. However, when it comes to even the most minimal stages of the ORIE technology being applied a much better image for study in black and white images present itself. This is seen in the next image below.  (Left and Middle images)- the are the best black and white images that current technology can produce.(Image Credit-(NASA / ESA)-(2004) Yet not much can be derived from either of these as far as through scientific investigation goes. (Right) is the image in which ORIE has been applied to. The dramatic difference can be clearly seen. A great amount of surface detail here can be seen. Plus, the two small white dots to the left of the ORIE image to the right, bring out so much detail in just a black and white image that thee two smaller white appearing dots, may be two satellites orbiting around Ceres. |

|

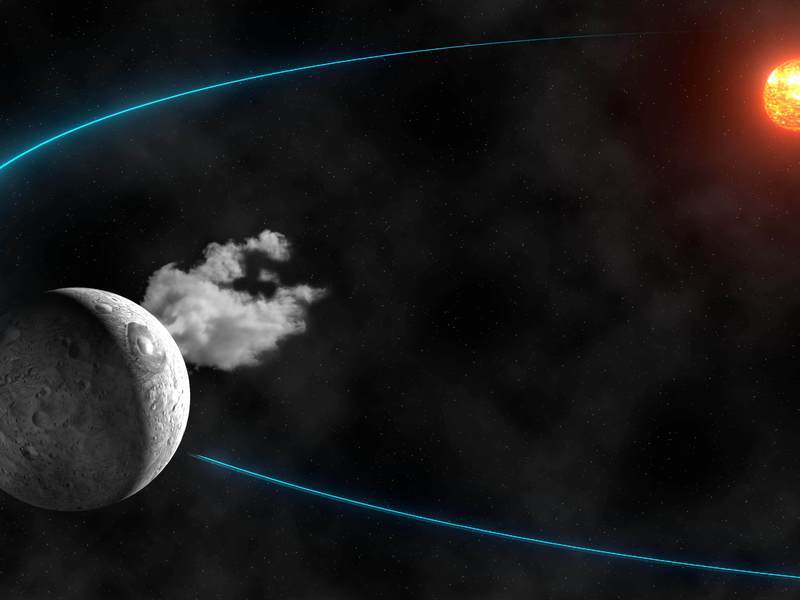

Ceres

Vents Water Vapor

Artist’s

rendition of the water vapor spewing from dwarf

planet Ceres,

which is shown in its orbit around the sun. (IMCCE-Observatoire de Paris/CNRS/Y.Gominet) Several other moon and planets in our solar system have shown us they are alive by spewing geysers of water and other materials into space while we had our eyes on the. Now we can add the Dwarf Planet Ceres to the collection Ceres, the largest asteroid in the solar system, lets off steam Twin jets on asteroid Ceres, which has a surface area roughly the same as India, release 21 tonnes of water vapour every hour Astronomers have spotted jets of steam coming from opposite sides of the largest asteroid in the solar system. The twin plumes of water vapour erupting from the space rock were noticed during a series of observations with the Herschel Space Telescope between October 2012 and March last year. Researchers said the steam was produced either by the warmth of the sun vaporising ice beneath the surface, or a form of volcanic activity that is forcing water out of the asteroid's warm interior. The scientists' calculations show that Ceres, technically a dwarf planet, releases around 21 tonnes of water vapour every hour from two dark patches on the surface. The amount is small for a ball of rock that measures 950km across and has roughly the same surface area as India. Ceres, the largest asteroid in the solar system, lets off steam Ian Sample, science correspondent theguardian.com, Thursday 23 January 2014 04.38 EST |

|

All material on these pages, unless otherwise noted, is © Pegasus Research Consortium 2001-2019 |

Webpages © 2001-2019 Pegasus Research Consortium |