|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

My Life in Forbidden Lhasa ...

|

|||||||||||||||||

| My Life in

Forbidden Lhasa

Published: May 2008 National Geographic Escaping from

internment in India

to the sacred capital of Tibet, an Austrian became

the Dalai Lama's trusted

tutor

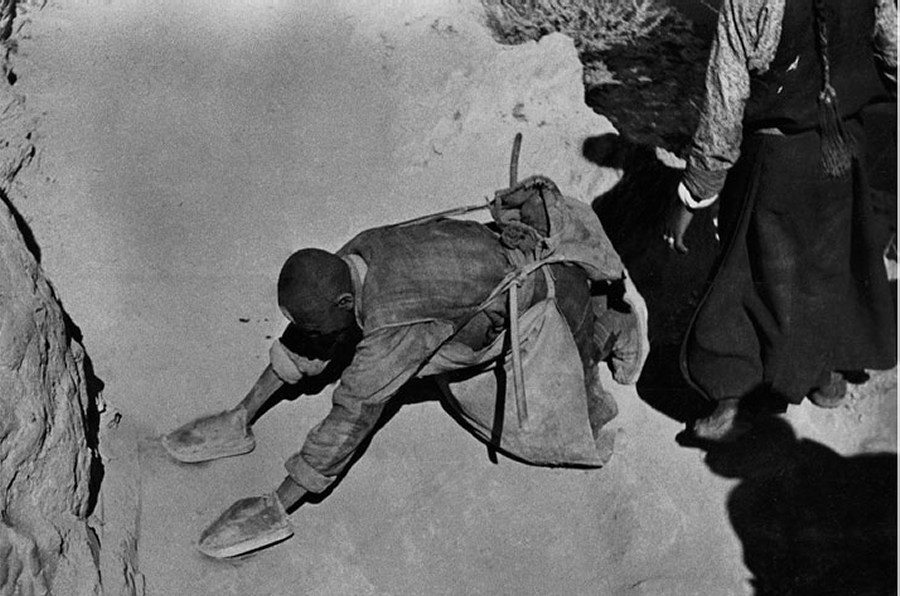

The rocky trail led into the broad valley of the Kyi River. Exhausted, our shoes in tatters and our feet bleeding and blistered, we rounded a little hill. Before us lay the Potala, winter palace of Tibet's Dalai Lama, its golden roofs ablaze in the January sun. Lhasa was only eight miles away! I felt a sudden compulsion to sink to my knees and offer a prayer of thanksgiving, even as did the Buddhist pilgrims who were our companions. It seemed impossible that we had reached safety, that our agony of cold and hunger and danger lay behind us. We had walked more than 1,500 miles across the most forbidding terrain in the world and had climbed 62 mountain passes, some as high as 20,000 feet. It is just as well, I have since felt, that no man can foretell the future. What would Peter Aufschnaiter and I have thought, when we left our native Austria in 1939 as members of the German Nanga Parbat Expedition, had we known we faced long imprisonment and a desperate escape into Tibet, where we were to roam fabled Lhasa with a color camera? War had trapped our expedition in Karachi. Enemy aliens, we were interned in a British prisoner-of-war camp in India. We mountaineers decided to attempt an escape over the towering Himalayas. I drew maps, studied Tibetan, hoarded money and medicines and other essentials. After several abortive breaks we reached freedom. Our comrades, appalled by the hardships, turned back, but Aufschnaiter and I had struggled and bluffed our way across Tibet's desolate Chang Tang, a wasteland that even the natives shun in winter (pages 6 and 10). We had subsisted on raw yak meat and yak-butter tea and dried meal. And now at last, after 21 months of wandering in which we had almost given up hope, the golden roofs of the Potala were in sight. Even now our troubles were not at an end. We were trespassers in Tibet, unwelcome foreigners in a land where every man is forbidden to assist a traveler who lacks written authority to pass. Our clothes were in rags, our appearance unkempt and forbidding. We had no baggage animals and no money to hire them. Surely the gates of the holy city would be closed to us. We decided on one last desperate gamble. At Shingdongka, the last village between us and Lhasa, we searched out the binpo, or local official. With as much authority as one can command in filthy sheepskins, we introduced ourselves as the advance guard of an important foreign emissary and demanded pack animals and an escort to Lhasa. Even now our troubles were not at an end. We were trespassers in Tibet, unwelcome foreigners in a land where every man is forbidden to assist a traveler who lacks written authority to pass. Our clothes were in rags, our appearance unkempt and forbidding. We had no baggage animals and no money to hire them. Surely the gates of the holy city would be closed to us. We decided on one last desperate gamble. At Shingdongka, the last village between us and Lhasa, we searched out the binpo, or local official. With as much authority as one can command in filthy sheepskins, we introduced ourselves as the advance guard of an important foreign emissary and demanded pack animals and an escort to Lhasa. Miraculously, the bonpo believed us. A donkey and driver were placed at our disposal. As in a dream, we walked the last few miles to Tibet's capital. The valley of the majestic Kyi River fanned before us like a great carpet. Tilled fields and marshes and parks bordered the flat plain that runs unbroken to a towering wall of naked, sloping mountains. In the crystal air of the Roof of the World the panorama seemed perfect beyond reality. The Potala's red and white facade loomed larger and larger. The 300-year-old palace crowns one of two jagged ridges which rise like sentinels from the valley floor. It wore an air of supernatural grandeur, as if it welled up in massive slabs of stone from the earth itself.

Gate Marks End of Flight We stood before the three giant chortens, or stupas, that bridge a gap between the Potala and neighboring Chagpori. A red-robed monk emerged from an archway in the central chorten. Here was the gateway to Lhasa, the end of the torturous road we had traveled. The monk turned aside, and Aufschnaiter and I looked at each other in anxiety. Where were the guards? I had visions of being thrown into a dungeon or, worse, turned back. To our amazement, only beggars stood vigil at Lhasa's gate. It was, we learned later, believed impossible for unauthorized travelers to reach the sacred portals. No sentinels were considered necessary. A wide street opened before us. Peddlers displayed a tempting assortment of delicacies, and the aroma nearly drove us mad. We had walked 25 miles that day without a bite to eat. But we had no money for food. Our last rupee must go to the donkey driver. Low, flat-topped houses built of stone and mud lined the streets. Prayer flags fluttered from every roof. It was dusk, and the warmth of the afternoon sun yielded to the bitter chill of Tibetan winter. We must find shelter, but Tibet has neither restaurants nor inns. Hesitantly we approached a house. A servant girl's face froze in horror. We retreated into the street, conscious of our fierce unTibetan beards and wretched clothes. At the next house another maid shouted abuse until we fled the courtyard. Our donkey driver was bewildered. He could not understand why the advance guards of an important foreign personage did not go where they were supposed to and stop wandering around. At the far side of town we reached a fashionable neighborhood and paused before a fine-looking establishment. We could go no farther; our weary limbs were through. We marched into the mansion's courtyard, paid off the donkey driver, and collapsed beside our scanty possessions. A maid fled, screaming as if pursued by demons. An incredible number of people crowded into the courtyard. Dogs barked, servants and family alike shouted. And every voice was crying: "Do not come! Do not come !" Aufschnaiter and I could not budge. Gingerly I pulled off the remains of my homemade yak-skin boots. My feet were covered with broken blisters, bleeding, hot, and raw. The throng stared, incredulous, at our torn feet. They forgot their fear of punishment for aiding a forbidden foreigner. A woman who had turned us away from her own home, then followed us in curiosity, offered yakbutter tea. The emulsion of rancid butter, boiled tea, salt, and soda tasted like nectar. Others brought tsampa, a parched barley flour that with tea forms Tibet's staple diet. "From where do you come?" someone asked. "From the Chang Tang."

Journey Astonishes Lhasans The word spread through the courtyard and into the street. The crowd was amazed that we spoke Tibetan, even more astonished that we had crossed the Chang Tang. The jostling group parted to admit an imposing Tibetan in red-wool cloak and violetsilk robe. "Tell me, please, who you are." He spoke in faultless English. At first he refused to believe there were only two of us. News of our progress through town had spread like wildfire. Officials had received so many reports of strangers stalking the streets that they had got the impression a minor invasion was under way. The nobleman said he would take us into his house if the Government would permit it. He went to the magistrate to ask authorization. An excited woman identified our benefactor as Thangme, the Master of Electricity. Permission was granted for our temporary shelter, and a servant led us to the nobleman's house. Thangme and his young wife greeted us warmly. Their five plump children gazed in wonder. The next day the Foreign Ministry sent word that we could stay with Thangme, under house arrest, until the Tibetan Regent returned from a distant retreat. The Regent, ruler of the nation until the 11-year-old Dalai Lama reached his majority, would decide our future. The Tibetans are, by nature, a generous and warmhearted people. Now that they could legally receive us, every luxury was heaped upon us. The Government sent us custom-made suits and shoes. The Thangmes crowded themselves to give us a pleasant bedroom of our own. The sweet incense of burning juniper poured from its iron stove. This was a great luxury, for Lhasa has no forests, and wood is borne from great distances by yaks. Even noble families customarily burn only yak dung.

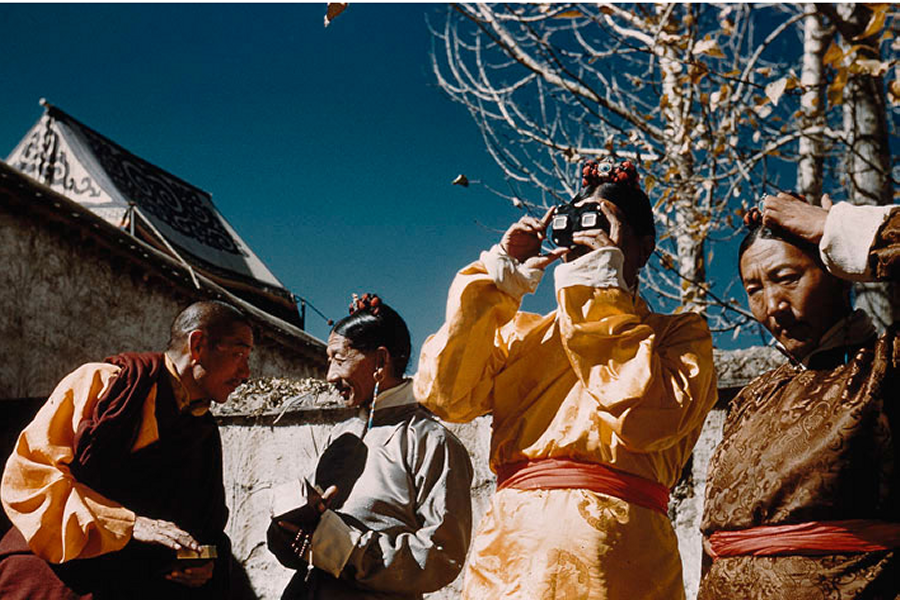

Strangers Become Social Lions We became the sensations of Lhasa. Aristocrats in fur-lined brocades and silks streamed to the Thangme home, bringing gifts. Everyone took great delight in our tale of how we had hoodwinked the Shingdongka official. The visit of George Tsarong, a Government official and the son of a former grand minister, set the house in an uproar. Tsarong was of higher rank than Thangme, and under Lhasa's rigid protocol would not ordinarily visit his home. The young aristocrat, however, proved a diverting guest. He had learned English in a British school in India, as had Thangme. Tsarong listened daily to news on a radio, powered by a wind-propelled generator, which he had put together himself. From him we learned of the events that followed World War II. Despite the end of hostilities, we were not anxious to return home. Yangchenla, Tsarong's wife, bubbled with laughter and questions. One of Lhasa's fairest women, she customarily dressed in a rainbow-striped apron and a triangular Lhasastyle headdress studded with turquoises, coral, amber, and seed pearls. She knew the use of rouge, lipstick, and powder. Other ranking nobles came to see the strangers and stayed deep into the night. Aufschnaiter and I worried lest we inconvenience our host and hostess, but they assured us they had never known such an exciting time. Our status as minor celebrities, however, did nothing to ease our worry over the future. The Regent had not yet returned to Lhasa, and until he made his decision we were living on borrowed time. Then, eight days after our inauspicious arrival, we were summoned to the home of the Dalai Lama's family. The impression we made, we felt, might influence the Regent's decision. We listened intently as the Thangmes instructed us how to behave. Generously they supplied us with white silk ceremonial scarves to present to the "Great Mother" and "Great Father." Tibetans of all ranks exchange these scarves, called khatas, in the manner of calling cards. At the door of the family's three-story mansion, standing in a garden at the foot of the Potala, we found an eight-foot prayer wheel that is turned day and night by men hired for the job. We ascended to the second floor. The Gyayum Chemo, the Dalai Lama's mother, sat in queenly grace on a modest throne in a room vivid with frescoes and carved pillars. Stretching our arms full length, we offered the silken scarves. She smiled; then, unexpectedly, she shook our hands, a custom alien to Tibetans.

Mother of Three Living Gods The First Family proved as eager as the Thangmes' guests to hear of our crossing of the Chang Tang. The Dalai Lama's father, a tall, pig-tailed man with thinning hair, joined us for tea. Lobsang Samten, their 14-year-old monk son, set upon us with questions and made it perfectly clear that the Dalai Lama expected to hear from him a full account of our visit. Lobsang later became one of my best friends. The Great Mother has led a remarkable life. Until the recognition of her son as the incarnation of Chenrezi, Tibet's patron god, the family had been simple farmers in a mountainous border region of China's neighboring Tsinghai Province, where many Tibetans live. She attained almost regal status overnight. Yet she bore herself with the confident poise of a lady born. "It has been our privilege," she smiled, "to give three sons to the Church. Our eldest son, Tagtsel Rimpoche, was recognized long ago as an incarnation. Lobsang, here in the robes of a monk, is destined to a celibate life and service as a Government officer. Another boy is in school in China. Our fourth son was found to be the Esteemed King when he was two years old." A month later the Gyayum Chemo gave birth to a fifth son. He, too, was recognized as an incarnation. Unconsciously, the Great Mother minimized the existence of two daughters, both living in the family home. Despite their happy dominance of the household, women have no voice in Tibet's public affairs.

Ruler Has Many Names Tibetans, our hosts explained, never use the expression "Dalai Lama," Mongolian for "Wide Ocean." His subjects speak of the venerated ruler as Gyalpo Rimpoche, "Esteemed King." To his immediate family he is Kundun, "the Presence." Later, I also was allowed to use this familiar term. Our hostess indicated that our interview was ended. She presented each of us with a 100-sang note, the equivalent of about $5. "I have an order from the Kundun to help you in every way," she smiled. "Whatever you need, it is my wish that you tell me." Aufschnaiter and I strolled home in an exuberant mood. Servants bobbed behind us carrying gifts: sacks of tsampa meal, skin pouches bulging with yak butter, and luxurious Tibetan wool blankets. Soon after our visit, the Foreign Ministry sent word that we were free to roam in Lhasa. Immediately we learned the overpowering sounds, sights, and smells of the sacred city.* I explored shop after shop, a series of open cells in the thick walls of private homes. I never ceased to wonder at the variety of goods available in Lhasa bazaars: brick tea, silks, and brocades from China; American cosmetics and fountain pens; aluminum and copper ware, luxurious furs, Swiss watches, yak meat and butter, and ornaments of the dark Tibetan gold that is still scratched from the earth with gazelle horns. At dusk each evening I found everyone promenading around the Barkhor, a main street that encircles Tibet's holiest cathedral, the Tsug Lag Khang. I passed flirts and pilgrims, smelled sacred incense and barley beer. Laughter echoed with the cathedral's perpetual chorus of drumbeats, oboes, and deepthroated prayers.

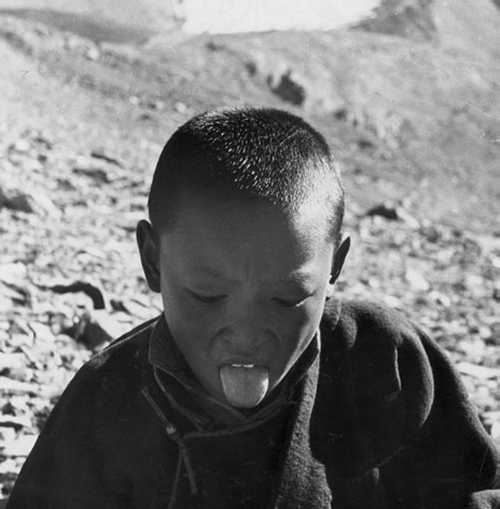

Monk Offers Support The fascination of our daily explorations could not erase the uncertainty of our position. First, we needed permission to remain in Lhasa. If that was granted, we would still face the necessity of earning a living. And then, one day on the street, a servant in a scarlet-fringed hat stopped us. He stuck out his tongue and hissed, that most surprising Tibetan gesture of respect, and announced that his master wanted to see us. The Triinyi Chemo, one of the monk secretaries who supervise Tibet's priesthood, questioned us about our education. Aufschnaiter's experience as an agricultural engineer seemed to impress him. "I would like to see you stay," he said. "We in Tibet could use men like you. Unhappily, everyone does not share my opinion. I will speak for you. But do not be hopeful." Despite the warning, his promise of support heightened our hopes. A monk patron would be most helpful to our appeal, because the allpowerful Tibetan priesthood normally resists foreign intrusions. Next day, Aufschnaiter and I made formal calls on the four members of the Kashag, or grand cabinet. These dignitaries are responsible only to the Dalai Lama and the Regent. Entitled Shapes, they manage the secular affairs of the country (page 28). We told them of our willingness to work for the Government and urged them to support our plea for asylum. While we waited for the Regent, spring breathed upon Lhasa. The Hair of Buddha, a venerable weeping willow at the cathedral's gate, turned golden green. Tender shoots spread an emerald haze along the Kyi River. With spring came the dust storms. Everyone rushed for home when the cloud rolled up the valley. The Potala disappeared in the swirls of prying, suffocating powder. Tsarong Shape, one of the dominant figures in 20th-century Tibet, invited us to move into his own palatial home. This shrewd man had been a favorite of the preceding Dalai Lama (the 13th), a member of the Kashag, and commander in chief of the Tibetan Army. The Government gave him vast estates. He fell from favor, but clung to his wealth and rank. We knew him as Master of the Mint. We had been settled in our new residence only a week when we received an urgent message: "The Austrians must leave the country immediately. Such is the decision of the Regent." The order was catastrophic. Not only did it condemn us to further wanderings, but the sciatica which I had developed on our long marches in 30-below-zero weather had grown worse. At times I could hardly move. We composed a long appeal for postponement. The reply came immediately in the form of an army lieutenant and three soldiers. The officer had orders to escort us to India, he announced, and we must be ready to leave the next day. In desperation, Aufschnaiter insisted that the Government ask the British Legation's medical officer to examine me. Reluctantly the authorities agreed. The British physician promptly certified that I could not possibly travel. He gave me injections, but I found more comfort in an exercise prescribed by a lama: rolling a stick beneath my bare feet.

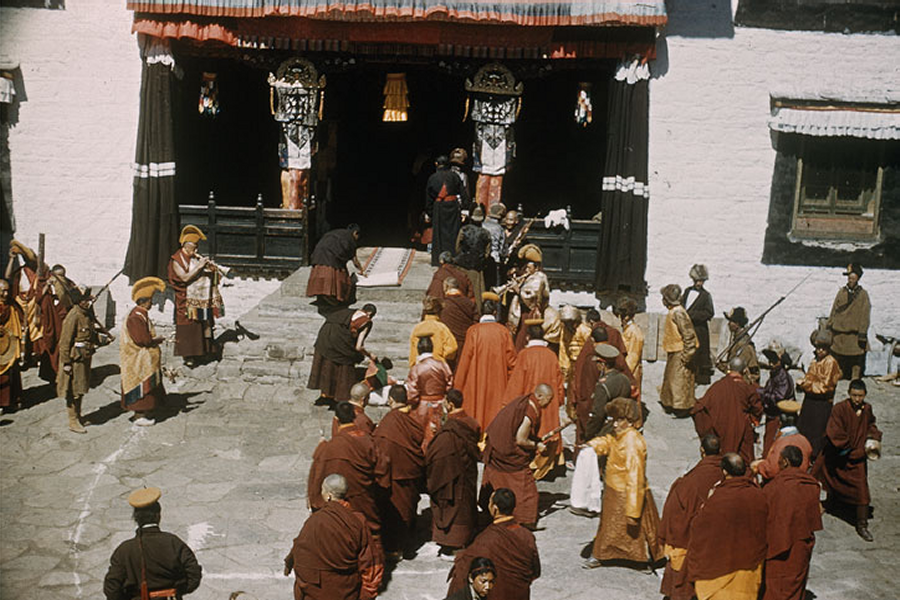

Religious Frenzy Sweeps Lhasa For a time we heard no more about expulsion. Fortunately for us, the officials had more important things to occupy their attention. March had come, and with it the greatest of Tibetan celebrations, the New Year Festival. Tibet's New Year started with a roar. An avalanche of 20,000 red-robed monks streamed into the holy city, doubling its population. The cacophony of prayers, drums, and cymbals echoed night and day. I dragged myself to the roof of Tsarong's mansion and watched the city whip itself into a religious frenzy. Work stopped. Offices were closed. Men and women appeared in their newest silks and brocades. Cabinet ministers and tradesmen, nobles and peasants, all prayed and danced and sang. Crowds shuffled clockwise along holy walks girding the Potala, the cathedral, and city. An accident marred the advent of "Fire Dog Year." A colossal flagpole fell in the Barkhor, killing three monks and injuring several others. Tibetans paled when they spoke of the evil omen. To them it augured distress, earthquakes, perhaps a devastating war. During the 21-day "Great Prayer," the civil government retired. Stern monk proctors from neighboring monasteries ruled Lhasa with an iron hand. The Dob-Dobs, brawny monk policemen who blacken their faces and pad their shoulders to make themselves more terrifying, swaggered about the city.

Intricate Sculptures in Butter The celebration reached its climax at the Butter Festival on the New Year's 15th day. Tsarong warned us not to venture into the unruly, hustling crowds. He stationed us with Mrs. Tsarong in one of his houses on the Barkhor. After sundown, monks towed towering sculptures of yak butter, pigmented with dark and vibrant dyes, into the Barkhor. Throngs gathered to admire the grinning caricatures of gods, the elaborate flower patterns, and intricate filigree work, fixed to pyramidal wooden stands 30 feet high. Mrs. Tsarong explained that months of work go into the displays. Each monastery maintains a workshop where its own artists shape the cold-hardened butter. The Government awards a prize to the best entry. The gallery of art stood ready. As we watched, hundreds of butter lamps and gas lanterns flickered in the darkness, conjuring a semblance of life into the effigies. Suddenly we heard trumpet blasts and the deep rumble of drums. The Dalai Lama stepped from the cathedral. He looked straight ahead, his almond-shaped face inscrutable beneath a peaked yellow-silk cap. For the first time I looked upon the god-king, the 14th incarnation of Tibet's patron god, Chenrezi. The 11-year-old boy gazed down upon thousands of bowed heads. To them he was a living god. The grave little King paced slowly along the array of grotesque images. Abbots supported him, their hands beneath his arms. The highest officials of the State followed. It was an electrifying tableau. The Dalai Lama withdrew into the cathedral. At once a religious madness seemed to seize the throngs. All night long we heard cries, weeping, and laughter, punctuated by the hoarse shouts of Dob-Dobs. Next morning the butter images were gone from the Barkhor, melted down for use in lamps or magic potions. Theirs was a single night of splendor, as if to remind mankind that beauty is temporal. The festive season ended, and Lhasans settled into routine. Pilgrims marched back toward the thawing northern plains. Unexpectedly Aufschnaiter joined the ranks of the employed. The Government commissioned him to construct an irrigation channel. I helped measure the course, but could not work because of my plaguing sciatica.

Fountain Fascinates Tibetans Idle days in Tsarong's sunny garden gave me an idea. I designed and supervised the building of a fountain. Tsarong was delighted. No one had ever erected a fountain in Lhasa, and his guests never tired of watching the sparkling jet. I found another way to occupy my time. Several noblemen engaged me to give lessons in mathematics and English to their sons. Lhasa maintained only one school for the nobility, a Government institution where the boys were taught accounting and manners. One day the High Chamberlain called me to the Potala. He invited me to landscape the gardens of the Tsedrung, a special monastic order that staffs the Dalai Lama's entourage. If I produced picturesque results, he hinted, I might be asked to rearrange the Dalai Lama's private garden. I was just beginning the work when a Foreign Ministry official sent my hopes tumbling. "Henrig-la," he said, with obvious distress," the English doctor has certified that you are well enough to travel. The Government says you must leave at once." What would happen, we asked, if my sciatica returned? What if I collapsed on the road? Above all, who would finish the irrigation channel and the Tsedrung's gardening? The appeal was taken under advisement. I do not know what happened, but no one ever said another word about expelling us from Lhasa. Summer arrived, as usual, on the eighth day of the third Tibetan month. Fortunately the day was hot. The Government's lay officials trooped to the Potala, peeled off their furlined robes and fur hats, and handed them to servants. Then they put on light summer silks and summer hats, drank ceremonial tea, and returned home. If sleet had been falling, they would have performed the same ritual. In Tibet; seasons change according to the inconstant lunar calendar. And so does rigidly prescribed dress. Aufschnaiter and I pleaded our case to the Foreign Ministry. We had learned the art of Oriental diplomacy-pretend to acquiesce, but use every stalling tactic.

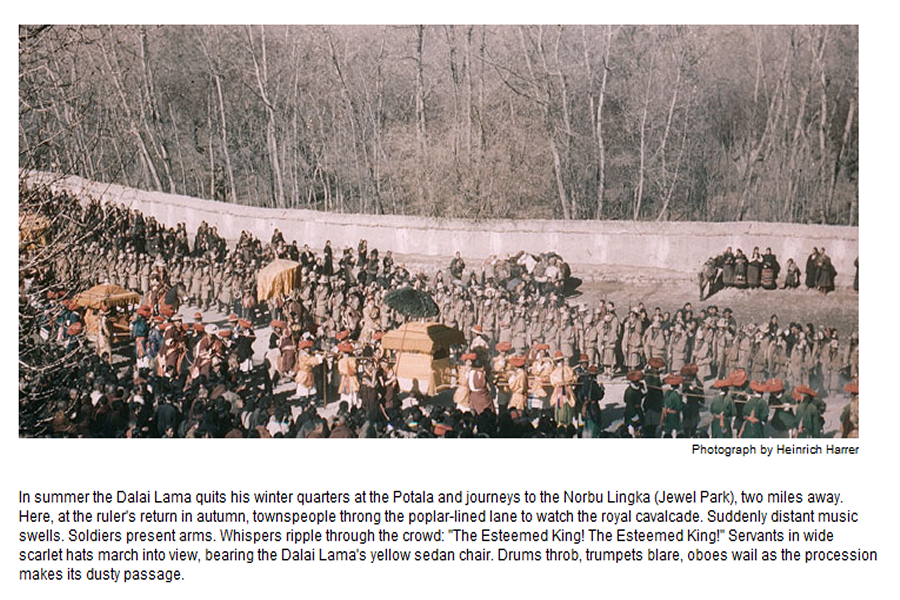

Trumpets Announce Migration A few days later I heard silver trumpets on the Potala roof. From monasteries in the valley came echoing blasts. The chorus proclaimed the Dalai Lama's annual migration from the Potala to his summer palace at the Norbu Lingka (Jewel Park). Townspeople hurried from every corner of Lhasa. When I reached the Western Gate, spectators stood six deep in the private lane between the Potala and the Jewel Park. Plumes of dust and incense heralded the cavalcade. An army of monk servants strutted by, carrying the Dalai Lama's silk-bound gear and favorite birds. There followed mounted musicians, baton-twirling drummers, cowled members of the ruler's monastic household, his giant bodyguards, and the commander in chief of the army. Then came the Living Buddha's yellow palanquin. It was borne at a swift, smooth pace by 36 colorfully robed servants in scarletfringed hats. Everyone of importance accompanied the venerated King to Norbu Lingka. The entire Government followed the palanquin in order of rank, riding horses with saddles of gold. It was an unforgettable spectacle, the profusion of gold and silks and jewels drenched in vivid sunshine under a cloudless sky. Lhasans Love Picnics Summer lay ripely upon Lhasa. Peach blossoms glazed the parks with pink. Blue and yellow poppies bloomed on the valley's hillsides. This was the picnic season, Lhasa's favorite time of the year. Entire families strolled from town each day to enjoy lazy pastimes on the riverbanks. Clicking dice games endlessly amused the men. At dusk, votive incense smoldered on the darkening shore. My swimming and diving fascinated the picnickers. Few Lhasans know how to swim, because the Kyi River is unpleasantly cold and treacherous. I suspected that I was invited on many excursions as a sort of vaudeville act. But my ability proved a blessing. I managed to save three persons from drowning, among them the 14-year-old son of Foreign Minister Surkhang. The episode led to an intimate friendship with the family. The Tibetans had by now accepted Aufschnaiter and me as citizens of Lhasa. We were consulted on every conceivable type of problem. Aufschnaiter completed the water channel, greatly increasing the irrigation potential in the plain bordering Lhasa. The Government then asked him to repair the creaking old electric plant which powered the mint near Lhasa. Coolies who brought the boxed parts from India 20 years earlier did not appreciate the delicate nature of their cargo. It was always suspected that some crates were rolled down the Himalayan slopes. True or not, the plant had never worked very well. An examination of the plant convinced Aufschnaiter that it could not be nursed to health. He proposed to harness the tumbling Kyi's water power. There was grave concern about the possible reaction of the river gods, but Aufschnaiter beguiled the Government into letting him undertake the project. I became, in effect, the information officer of the Government. A Foreign Ministry official sent me a radio receiving set. Each day I monitored English-language broadcasts from world capitals and transcribed any political news that I thought would interest Tibetan officials. At Christmas time I gave my first party to repay the extravagant hospitality of my friends. I shall always cherish the memory of their brotherhood. Christmas, of course, is meaningless in the holiest city of Lamaism, but my Tibetan comrades stood stoutly before an improvised Christmas tree and tried to sing "Silent Night." Now it was 1947—"Fire Pig Year." Aufschnaiter's name and mine appeared on the Dalai Lama's New Year reception list. We had heard that the young god-king took a keen interest in our activities and often watched us through binoculars. We shopped for the costliest silk scarves in Lhasa. On reception day we climbed the broad stone stairway to the Potala's main entrance in a procession of swarthy nomads, monks, and richly clad aristocrats.

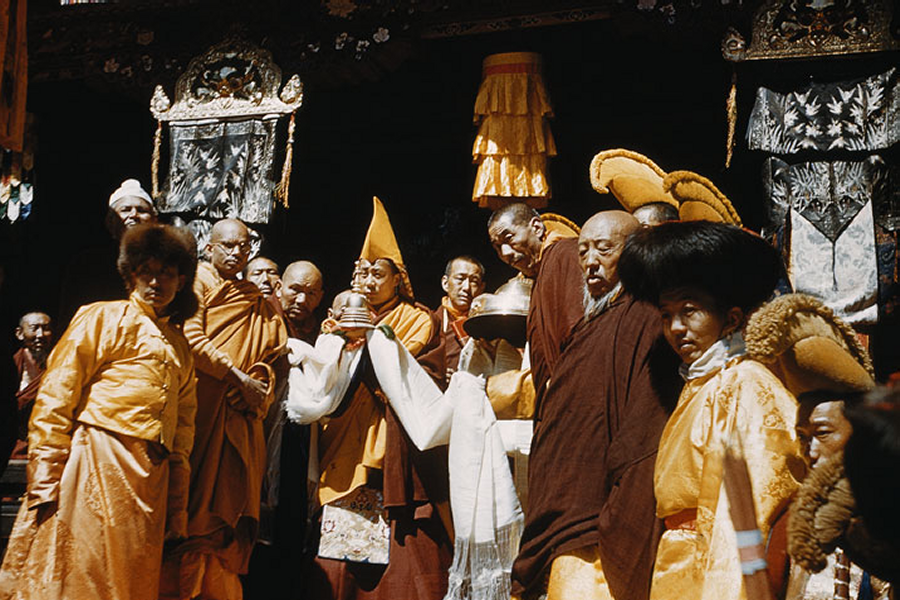

All Tibetans Eligible for Blessing Through the main portico, embellished with frescoes of grinning protective gods, the group entered into dark, winding passages. Finally we reached a small courtyard. Steep ladders led to a roof several stories higher. A crowd had already gathered, for any Tibetan citizen may receive the blessing of His Holiness at New Year. Step by step we pressed to the entrance of penthouse buildings with golden roofs. I stretched to glimpse the object of all Tibet's veneration, and saw him stretch to look at us! The young King sat cross-legged on a throne draped in rare brocade. Bags of money, rolls of glossy silk, and hundreds of ceremonial scarves mounted at its base. With grave preoccupation he tilted back and forth, bestowing his blessing on the pilgrims. They glided by, trembling, with heads bowed low and tongues stretched forth. When finally I stood before the throne, I could not resist a furtive upward glance. Our eyes met, and a quick smile animated the Dalai Lama's charming, finely chiseled face. I bowed to receive his blessing, an eager playful push that seemed to say, "Hello there! So you're the Westerner." An abbot steered Aufschnaiter and me into an obscure corner where we could watch the ritual. Many pilgrims had traveled hundreds of miles, some prostrating themselves foot by foot. Each brought a gift, if only a shabby scarf. An accountant recorded the more substantial gifts of money, destined to join the treasure that had been accumulating for centuries. Commoners Blessed with Tassel The Dalai Lama places his hands only on monks, Government officials, and esteemed visitors. He blesses other persons with a wave of a silken tassel. One woman outside his family merits the personal touch. She is the "Thunderbolt Sow," the only female incarnation, and thus the holiest woman in Tibet. When the ceremony ended, a monk handed us each a new 100-sang note and murmured, "A gift from the Treasured King." I still cherish the bill. Pilgrims are permitted to tour certain parts of the Potala. Impressive from the outside, it is a bitter disappointment within. Ageold gloom, dust, and the suffocating stench of rancid butter permeate every corner of its maze of passages and cells. The spillings of countless butter lamps make footing difficult. In contrast to the squalor, the remains of seven Dalai Lamas repose in golden stupas encrusted with dusty pearls, rubies, diamonds, turquoises, coral, and sapphires. A monk keeps vigil before each mausoleum, intoning prayers and thumping a drum. Once I asked a stonemason why Tibetans no longer raised buildings of the magnitude of the Potala. He assured me earnestly that gods created the Potala overnight long, long ago. "Who else could have erected a dwelling for a god?" he asked. "Who else would have had the strength and means to pile up mighty stone blocks on a mountain hundreds of feet high? No, the god who dwells there was the architect. And spirits created the Summit."

Potala Was Begun in 1641 The Potala, in fact, grew stone by stone with the sweat of many Tibetan brows. The fifth Dalai Lama started its construction in 1641 on the site of an old Tibetan citadel. Every subject was obliged to bring a stone block from a distant quarry. When the fifth incarnation died in 1680, the astute Regent suspected that laborers might continue their backbreaking journeys for a divinity, but not for him. He announced that the Dalai Lama was in seclusion and kept the ruler's death a secret until the Potala was completed nine years later. All of the Dalai Lamas are regarded as a single spirit occupying a succession of bodies. How is a new incarnation discovered? Kunsangtse Dzasa, then commander in chief of the Tibetan army, was one of the few witnesses to the recognition of the 14th Dalai Lama. One evening he told me the story: "When the 13th Dalai Lama became gravely ill in 1933, he gave vague hints about the place of his rebirth. After death, his body sat in state facing south. One morning the monks saw that his face had turned toward the rising sun. The State Oracle was called. When the gods had possessed his body, the oracle flung a khata toward the east. Vision of Home in Lake "The Regent journeyed to a holy lake whose waters reflect the future. In the mirrorlike surface he envisioned another lake. Beside the visionary body of water stood a peasant's home and a monastery with roofs of gold. The Regent hastened back to Lhasa. "The first search parties set out in 1937, carrying objects that the Great Thirteenth had used every day. They searched month after month. "My group journeyed to the Chinese Province of Tsinghai. You can imagine our excitement when we came to a monastery whose golden towers resembled those seen by the Regent. Beside it stood a humble house. We were convinced that we stood at the goal. "To conceal our intent, we changed clothing with our servants and entered the house. A little boy, about two years old, sprang up and ran to meet us. He clutched the soiled garb of a disguised priest and cried out, 'Sera lama, Sera lama!' We could hardly believe our eyes, for the priest did, in fact, come from the Sera Monastery. "Old and new objects were held before the boy. Without hesitation he chose the Great Thirteenth's favorite drum and walking cane. "On the child's body we found marks that the incarnation of Chenrezi should bearprominent ears, and moles on the upper part of the trunk. "Finally, in the summer of 1939, we returned with the Esteemed King and his family. All the people rejoiced because the embodiment had returned to the Summit. "During the next New Year Festival the Esteemed King was enthroned and given his new titles: the Holy One, the Glorious, the Mighty of Speech, the Enlightened Understanding, Absolute Wisdom, and the Wide Ocean."

Oracle Dances to Halt Rain The short monsoon season was heavier than usual during our second summer in Lhasa. The driving rains turned Lhasa's streets into a quagmire, the Kyi into a raging torrent. Soldiers routed me from bed one night. "Sir, the great Kyi threatens the summer palace of the Treasured King. You must come at once and hold the dikes." A horse was waiting. We splashed through muddy lanes to the levees. Our lanterns penetrated only a few feet in the murk, and there was little we could do but hope the dikes would stand until day. I searched the bazaars for jute sacks. These were filled with sand and turf. Then I set to work with 500 coolies and soldiers. At the same time, the weather oracle hastened from Gadong Monastery to perform elaborate dances on the riverbank. We both worked feverishly toward the same end. The dikes held. The rains stopped. The flood ebbed. Both the oracle and I received generous praise from the Dalai Lama. Having no knowledge of engineering principles, the Tibetans had built vertical dikes that gave before pressure. I was asked to erect a strong new barrier to withstand the summer floods. With Aufschnaiter's help, I began surveying in the spring of 1948 and shoveled the last spade of earth before the summer monsoon. The gently sloping dike, 1,800 feet long, diverted the river from its course alongside the summer palace to an uninhabited lowland. Dike Holds Back Flood When the first floodwaters spilled down the Kyi, the dike held like stone. We set out a grove of willows on land formerly inundated each year. Some 500 coolies and 1,000 soldiers were assigned to the project, the largest construction force ever assembled in Tibet. They were good fellows, noisy and happy-go-lucky, but it took three of them to man one shovel. There also were many slowdowns. Workers constantly brewed butter tea. Diggers took excruciating pains not to destroy a single living creature. There was a shriek of alarm every time a worker spied a worm or bug in newly turned earth. Work stopped while the tiny being was borne to safety. The Tibetans' religion teaches them that no life may be destroyed if death can be averted. The most devout went so far as to collect fish from ponds before winter's deep freeze and summer's drought. The fish were carried in pails to refuge in the Kyi. Life was full and busy. Aufschnaiter and I mapped Lhasa, making the first accurate survey with a theodolite and measuring tape. Friendly crowds gathered when we appeared with the equipment. Poor Aufschnaiter often found himself peering through the theodolite's telescope into a blurred Tibetan eye. We found it necessary to rise before dawn to get our work done. We started the survey with an antiquated theodolite belonging to Tsarong, but completed it with a fine new instrument sent to us by the National Geographic Society. The Government was already paying Aufschnaiter for his work in Lhasa. I, too, received a commission as a salaried official, fifth class, in 1948. My monthly salary amounted to about $120, worth three or four times as much in Lhasa as in the United States. We were asked to study the possibility of installing a modern drainage and electric system in the holy city. Neither of us had training in those engineering fields, but in Lhasa we were jacks of all trades. On one occasion we regilded idols in a temple. As a Government official in a city addicted to protocol, I felt that I should live in a home of my own. Foreign Minister Surkhang offered me one of his villas in a charming suburban garden. It was an unusual house and considered very modern because of its frontage of glass windows. I engaged a personal servant, Nyima. He was a husky, bright former soldier who insisted upon following me to homes of friends in the evening and waiting with pistol and sword to protect me on the way home. Nyima and I took care to tend the sacramentals at Surkhang's villa. He looked after the living-room altar, filling seven bowls of water for the gods daily. There were gay prayer flags and an incense burner on the roof. I stretched a radio antenna between two of the flags.

Visits to Provinces The Government occasionally lent me to nobles who wanted advice about improvements on their estates. Trips by horse and yak-hide boat into sparsely inhabited provinces opened new horizons for me in this lofty, remote country. Farming methods are entirely medieval. Farmers tear the stubborn soil with primitive wooden plows pulled by dzos. The dzo, a hybrid between the ox and yak, is gentler than the stubborn yak. In the provinces, Tibetans are inured to harsh, frugal lives. Daily food may consist of a bowl of tsampa kneaded with tea, a few strips of dried yak meat, and endless cups of greenish butter tea. But I have never known a people who laughed so much. Their casual attitude toward life finds its most startling expression in marriage. Most Tibetans have one mate, but any marital arrangement is tolerated. Brothers—or sisters—may wed the same partner to keep a family estate intact. Fortunately jealousy seldom stirs a Tibetan heart. Everywhere in the length and breadth of the starkly beautiful country there are monasteries. They perch like stone griffins' nests on the spurs of mountains and nestle halfhidden in green, sun-soaked valleys. "Every family is expected to give at least one son to the Church," a friend once told us. The vast majority of monks never rise above servility. Only a few become scholars. Winter froze a small tributary of the Kyi River. Lobsang and I found several pairs of ice skates in the city. Soon Lhasa youngsters were "walking on knives" with grim enthusiasm. The Dalai Lama, confined to his lonely rooms, heard about the skating parties on the Kyi. But the Chagpori Hill hid the rink from his binoculars' line of vision. Through Lobsang, the enterprising young King, who had become an ardent photographer, delivered a motion picture camera to me with instructions to film all the fun and festivals that he could not see. Through the camera's view finder I witnessed the medieval glory and daily life of his city. Lobsang searched me out one day and said, casually, "The Kundun has expressed the wish that you construct a cinema house at the Jewel Park. He is eager to see the films, and there is no projection room in the Summit or the summer palace." The command opened the gates of the Dalai Lama's sanctum, the Inner Garden, at Jewel Park. Assembling Lhasa's best craftsmen and soldiers, I converted a vacant building into a theater 60 feet long. The projection equipment was installed in the annex. The Dalai Lama thought the hum of modern machinery might annoy the old Regent, so we built a powerhouse some distance from the theater. The Government had provided a motor and generator, but I doubted whether the decrepit engine would last through the premiere. Tibet's trade delegation that visited the United States in 1948 had returned with a disassembled jeep among its souvenirs. The jeep was put together, given one trial run, then set to work in the Government mint near Lhasa. I suggested we commandeer the jeep as an auxiliary power unit, and the Dalai Lama quickly approved. When the jeep arrived at Jewel Park, a new dilemma arose. The gate in the Inner Garden's yellow wall was too narrow to let it pass. What should be done? Orthodox old monks shook their heads and agreed, "The wall cannot be touched. It has stood for many years, just as it was built in perfection by former Esteemed Kings." Defying tradition and the monks, the 14year-old Dalai Lama ordered the gate to be widened. And so it was. The episode presented a striking test of power. I had grown aware of the youth's independence of will and his intellect. He was worshiped as Tibet's greatest Living Buddha, but the Regent and abbots dominated him as a child. They did not favor construction of the theater. They knew that it would unmask an exciting new world to his eager, inquisitive mind. Spring, 1950, turned the Inner Garden into an enchanted oasis. The days grew warm, the grass green and thick. Peach and pear blossoms stirred amid tinkling bells. Strutting peacocks fanned their blue-green tails. An old gardener arranged fragrant flowers in the sun. Servants cleaned the many small houses in preparation for the Dalai Lama's arrival from the Potala. The cinema awaited its young manager when he moved in stately procession to the summer palace. As I focused the camera on his richly adorned palanquin, he peered through a curtained window—and smiled. ..

A Summons to the Palace After the cavalcade disappeared into Jewel Park, I rode back toward Lhasa. A panting bodyguard caught up with me, his red robe flapping like wings. "Kusho, Henrig-la! We have been looking for you everywhere. You are to return to the summer palace. They say you must hurry." "What now?" I thought. A mishap? Short circuit? Perhaps a fire? I galloped back to the Jewel Park. Lobsang appeared grinning at the entrance to the Inner Garden and handed me a ceremonial scarf. At the projection-booth door I came face to face with the Living Buddha. The Dalai Lama caught up my presentation scarf with his left hand and used his right to bless me with a spontaneous pat. "Henrig," he said, "you will teach me this language. We will start now." He learned quickly, noting the pronunciation of words in graceful Tibetan characters. He encountered one difficulty, the letter F, which is not used in Tibetan. At length he said, "It is my wish that you come tomorrow to the summer home of my family here in Jewel Park. I will send for you when I am free." Lost in thought, I walked through the silent garden. How remarkable, I thought, to find laughter, wit, and a compelling thirst for knowledge in a boy who grew up without playmates, committed to endless study of holy scriptures, surrounded by monks, cloistered in a gloomy palace. Although a god-king, he had received less personal attention than a poor peasant child. His brother Lobsang once described the Dalai Lama's daily routine: The boy gets up at dawn. He sleeps on an ordinary Tibetan bed-hard, wool-stuffed cushions. Servants bring butter tea, tsampa meal, soap, a small washbowl, and an American-made toothbrush. He prays until the 10-o'clock convocation of the Tsedrung, a special order of 175 monks who staff all clerical positions in the Government hierarchy. The Tsedrung reports to the Dalai Lama in a body each day. At 11 o'clock the Dalai Lama dines alone. At times his mother or Lobsang may call. He is free until 3 o'clock, when lessons begin. He studies until sundown, again eats alone, then goes to the Potala roof. His only diversion is scanning the gardens and streets with his binoculars. Massive silence envelops the Potala at night. The head treasurer locks and bolts all doors. A wraithlike watchman paces the empty corridors. Still alone, the Dalai Lama spends the evening reading or praying. Yet on his own initiative he adopted photography as a hobby and undertook to learn an alien language! Those hours in the Jewel Park's new cinema changed the course of my life in Lhasa. I was at the Dalai Lama's beck and call, and it was a sobering task to try to impart the knowledge and ways of my world to the godking of a country larger than England, France, and Germany combined. I worked hard to prepare for the daily lessons. In addition to absorbing English, geography, and mathematics, he asked questions of every nature. They ranged from Greenwich time to the composition of the atomic bomb. The pupil tried to convert me to Lamaism. The Dalai Lama confided that he was studying exercises to accomplish separation of the spirit from the body. When he felt absolutely sure of himself, he planned to send me on a mission to Gartok, in western Tibet, and direct my actions from the Potala. "Kundun," I said, smiling, "when you can do that, I shall become a Buddhist." ..

Bad Omens Upset Tibet The experiment never came to pass. The Chinese Communist tide surged across old Cathay, and the Nationalist Government withdrew to Formosa. Tibet feared invasion. Sinister omens left Lhasans pale and jittery. Tibetans said they had never heard of so many freak births among humans and animals, a certain sign that the gods were disturbed. On a hot summer day, water inexplicably dripped from a gargoyle on the cathedral in Lhasa. This was interpreted as a god's tears for their fate. A stone sphere fell from the tip of an obelisk commemorating a historic victory. Tibetans said they could not expect a more precise warning from the gods. Pilgrims limped into the holy city from distant provinces. Lhasans erected new prayer wheels and flags. Sacrificial fires flickered on mountain peaks. On August 15, 1950, I visited a friend's home in the evening. Guests encircled the gaming table. The dice rattled softly, but no one laughed or shouted "Tsack!" when he took his turn. Suddenly an earthquake shook the house. I counted 40 muffled detonations. That night an Indian newscaster reported titanic earthslides in Assam, but several weeks passed before Lhasa learned of the devastation in eastern Tibet. Country Prepares for Defense Lhasans were beside themselves with fright. It was rumored that the State Oracle was going through trance after trance in greatest secrecy and that all of his prophecies were discouraging. To arm itself for possible war, the land of lamas prepared both guns and amulets. Tibet is an intensely nationalistic country, and there was a surge of patriotic enthusiasm. A musician composed a new national anthem to replace "God Save the Queen," a tune imported from India many decades ago on the assumption that it was played everywhere on official occasions. Cries echoed in Lhasa: "Give the Dalai Lama the power!" The movement to shift control of Tibet's destiny from the old Regent caused the 15year-old Dalai Lama to pace the floor. He had not dreamed that he might be invested before his 18th birthday, and did not consider himself ready to fulfill his destiny as Tibet's absolute ruler. His fate was decided on October 7, 1950. Chinese Communist soldiers marched across the border. Grim-faced abbots and senior statesmen summoned all the major oracles.t The Dalai Lama witnessed violent scenes in the peaceful, autumn-tinted grounds of the Jewel Park. The State Oracle sat motionless, his head buried in his hands. Incense clouded and scented the air. There was a din: the hollow, rumbling rhythm of drumbeats and the thin whine of oboes. Now his face could be seen. The Oracle's features, in repose those of a handsome young man, grew rigid and waxen. Life seemed to be draining from his body. Then abruptly the Oracle jumped. He began to quiver, more and more violently, and hissing sounds escaped from his throat. Attendants heaved a towering 50-pound headdress into position. Despite its weight, his head tossed to and fro. Now he sprang up, his features twisted out of recognition. His face became purple and splotched. Sweat glistered on his brow. As the discordant music reached a furious pitch, he spun about on one leg, faster and faster, hammering a giant ring against his metal breastplate-until finally he threw himself at the Dalai Lama's feet and gasped, "Make him King!"

Other oracles uttered the same cry. The Dalai Lama had insisted on continuing his lessons. With his investment at hand, awaiting only an auspicious date, he had to bring his school days to a close. At our final meeting he expressed concern about Aufschnaiter's and my welfare. "It's best for you to leave Lhasa," he said. "You've worked hard and are due for a leave, anyway. Go now, Henrig. We'll meet again." I never saw the Dalai Lama again in the holy city. He returned to the Potala, where the Tsedrung kept him under heavy guard. The Government faced another momentous problem: Was he to remain in Lhasa or flee? The Oracle counseled flight. Sadly I said goodbye to Lhasa in November, 1950. Aufschnaiter decided to stay as long as possible. In a light yak-skin boat I floated down the Kyi River toward a rendezvous with my caravan. I gazed back at the great Potala, brooding and shadowed under a gray wintry sky. It receded farther and farther into the distance. At last I could see it no more. I lingered in southern Tibet, reluctant to leave the country that had sheltered me. Ruler Flees by Night Meanwhile, the Dalai Lama had been invested as ruler. Under cover of night he fled from Lhasa with an army of nobles, servants, and soldiers. Pious Tibetans hurried from far-off settlements to see him, for being in his presence gave incomparable blessing. They lined the entire trail from Lhasa to Chumbi Valley, 200 miles southwest, with parallel rows of pebbles to protect their harried King from evil spirits. I joined the caravan and rode with it to Chumbi, a sunny green oasis nestled between Bhutan and Sikkim. There I awaited some resolution of the crisis. In March, 1951, having concluded that I could not go back to Lhasa, I set forth for India. The Dalai Lama had received me several times at his monastic retreat, but there was no chance to say farewell. Riding south, followed by servants, luggage, and horses, I envisioned the changes that were to take place in Tibet, the roads to be carved in its face, the rumbling trucks that were to roll in Lhasa. I felt certain that the Dalai Lama would return to the holy city within a few months. He did so, still the nominal ruler but a deity without true secular power. I hoped that Tibet's patron god, through the extraordinary young man I had humbly tutored, would protect the land of lamas. There were no barriers, guards, or customs inspectors at Tibet's borders. As I stepped into Sikkim, I recalled an old prophecy that the 13th Dalai Lama would be the last of the line. And my 15-year-old friend, newly invested as the 14th Dalai Lama, had not enjoyed a day of independent, untroubled rule. But I also recall his hopeful words at our final lesson: "Go now, Henrig. We'll meet again." © 2009 National Geographic Society. All rights reserved. SOURCE: National Geographic |

|||||||||||||||||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |||||||||||||||||

|

|