Comte de Saint Germain, a.k.a. "The Professor"

THE MYSTERIOUS ROSICRUCIAN WHO WAS

THE FATHER OF THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC

Great Secret: Count St. Germain

by Raymond BernardThroughout his life, Francis Bacon's fondest hope was the, creation of a Utopia across the Atlantic, the realization of his "New Atlantis" in the form of a society of free men, governed by sages and scientists, in which his Freemasonic and Rosicrucian principles would govern the social, political and economic life of the new nation. It was for this reason why, as Lord Chancellor, he took such an active interest in the colonization of America, and why he sent his son to Virginia as one of the early colonists. For it was in America, through the pen of Thomas Paine and the writings of Thomas Jefferson, as well as through the revolutionary activities of his many Rosicrucian-Freemasonic followers, most prominent among whom were George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, that he hoped to create a new nation dedicated to his political philosophy.In his Secret Destiny of America, Manly Hall, Bacon's most understanding modern scholar, refers to the appearance in America, prior to the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, of a mysterious Rosicrucian philosopher, a strict vegetarian who ate only foods that grew above the ground, who was a friend and teacher of Franklin and Washington and who seemed to have played an important role in the founding of the new republic. Why most historians failed to mention him is a puzzle, for that he existed is a certainty.

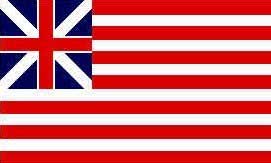

He was known as the "Professor." Together with Franklin and Washington, he was a member of the committee selected by the Continental Congress in 1775 to create a design for the American Flag. The design he made was accepted by the committee and given to Betsy Ross to execute into the first model.

A year later, on July 4, 1776, this mysterious stranger, whose name nobody knew, suddenly appeared in Independence Hall and delivered a stirring address to the fearful men there gathered, who were wondering whether they should risk their lives as traitors by affixing their names to the memorable document which Thomas Jefferson wrote and of whose ideals Francis Bacon, founder of Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism, was the true originator.

The flag unfurled at Cambridge, Mass. in 1775, which the Professor designed, symbolized the union of the colonies; it was called the Grand Union Flag, and its design was as follows: In the blue field of the upperleft-hand corner was the white diagonal cross of St. Andrews. Imposed on this was the Red Cross, which was given the name of St. George. The thirteen stripes, seven of red and six of white, alternating in the flag, represented the thirteen colonies. The flag was used for some time, but owing to its similarity with the British flag, which supposedly symbolized the unity of England and Scotland, considerable controversy arose over it. In order to overcome this objection, in 1776 it was decided to design another flag which would follow the spirit of the original design; and the inverted triangle over the upright triangle, generally known as the St. Andrew's Cross, a Masonic symbol of Kabbalistic origin and denoting that the originator of the flag was a Freemason and Rosicrucian, was preserved by using a six-pointed star, placed in irregular fashion on a blue back-ground in the form of a new constellation.

When General Johnson and Doctor Franklin visited Mrs. Elizabeth Ross, otherwise known as Betsy Ross, to get her cooperation in making the flag, the five-pointed star appealed to her as being more beautiful than the six-pointed star of the Professor's original design which the committee accepted. Hence, out of deference to her sense of beauty, the five-pointed stars were used instead, and thirteen of them were placed in a circle on a blue field with the standard seven red and six white stripes completing the flag.

This sample flag was made just before the Declaration of Independence, although the resolution endorsing it was not passed by the Continental Congress until July 14, 1777. A second time did this mysterious stranger, the "Professor," whose name and origin was unknown, pay a vital role in American history. This time it was at the signing of the Declaration' of Independence. It was on June 7, 1776, that Richard Henry Lee, a delegate from Virginia, offered in Congress the first resolution declaring that the United Colonies were, and of right ought. to be, free and independent states. Soon after Mr. Lee introduced his resolution, he was taken sick and returned to his home in Virginia, whereupon on June 11th, 1776, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert Livingston were appointed as a committee to prepare a formal Declaration of Independence.

On the first of July, 1776, the committee made its report to Congress. On the second of July, Lee's resolution was adopted in its original words. During the third of July, the formal Declaration of Independence was reported by the committee and debated with great enthusiasm. The discussion was resumed on the fourth, Jefferson having been elected as chairman of the committee.

On July 4th, there was great suspense throughout the nation. Many were adverse to severing the ties with the mother country; and many feared the vengeance of the king and his armies. Many battles had been fought already, but no decisive victory had been won by the rebel colonists. Each man in the Continental Congress realized as Patrick Henry did that it was either Liberty or Death. A rash move could mean death. After all, they were not free but subjects of a king who considered them as rebels and could punish them accordingly. They could be convicted for treason and put to death.

Just what connection did the mysterious stranger who designed the American flag and encouraged the signing of the Declaration of Independence have to Francis Bacon or Count Saint-Germain? Writing on this subject, Manly Hall says:

"Many times the question has been asked, Was Francis Bacon's vision of the "New Atlantis" a prophetic dream of the great civilization which was so soon to rise upon the soil of the New World? It cannot be doubted that the secret societies of. Europe conspired to establish upon the American continent 'a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.' Two incidents in the early history of the United States evidence the influence of that secret body, which has so long guided the destinies of peoples and religions. By them nations are created as vehicles for the promulgation of ideals, and while nations are true to these ideals they survive; when they vary from them, they vanish like the Atlantis of old which had ceased to 'know the gods.'"In his admirable little treatise, "Our Flag," Robert Allen Campbell revives the details of an obscure, but most important, episode of American history—the designing of the Colonial flag of 1775. The account involves a mysterious man concerning whom no information is available other than that he was on familiar terms with both General Washington and Dr. Benjamin Franklin. The following description of him is taken from Campbell's treatise:"Little seems to have been known concerning this old gentleman; and in the materials from which this account is compiled, his name is not even once mentioned, for he is uniformly spoken of or referred to as 'the Professor.' He was evidently far beyond his threescore and ten years; and he often referred to historical events of more than a century previous just as if he had been a living witness to their occurrence; still he was erect, vigorous and active—hale, hearty and clear-minded, as strong and energetic every way as in the prime of life. He was tall, of fine figure, perfectly easy, very dignified in his manners, being at once courteous, gracious and commanding. He was, for those times, and considering the customs of the Colonists, very peculiar in his method of living; for he ate no flesh, fowl or fish; he never used for food any 'green thing', any roots or anything unripe; he drank no liquor, wine or ale; but confined his diet to cereals and their products, fruits that were ripened on the stem in the sun, nuts, mild tea and the sweet of honey, sugar and molasses. [ Editor's note: The Comte de Saint Germain's same abstemious behavior regarding food was well documented in Europe.]"He was well educated, highly cultivated, of extensive as well as varied information, and very studious. He spent considerable of his time in the patient and persistent scanning of a number of very rare old books and ancient manuscripts which he seemed to be deciphering, translating or rewriting. These books, and manuscripts, together with his own writings, he never showed to anyone; and he did not even mention them in his conversations with the family, except in the most casual way; and he always locked them up carefully in a large, old-fashioned, cubically shaped, iron-bound, heavy oaken chest, whenever he left his room, even for his meals. He took long and frequent walks alone, sat on the brows of the neighboring hills, or mused in the midst of the green and flower-gemmed meadows. He was fairly liberal—but in no way lavish—in spending his money, with which he was well supplied. He was a quiet, though a very genial and very interesting member of the family; and he was seemingly at home upon any and every topic coming up in conversation. He was, in short, one whom everyone would notice and respect, whom few would feel well acquainted with, and whom no one would presume to question concerning himself—as to whence he came, why he tarried or whither he journeyed."

"By something more than a mere coincidence, the committee appointed by the Colonial Congress to design a flag accepted an invitation to be guests, while at Cambridge, of the family with which the Professor was staying. It was here that General Washington joined them for the purpose of deciding upon a fitting emblem. By the signs that passed between them, it was evident that General Washington and Doctor Franklin recognized the Professor, and by unanimous approval, he was invited to become an active member of the committee. During the proceedings which followed, the Professor was treated with the most profound respect and all his suggestions immediately acted upon. He submitted a pattern which he considered symbolically appropriate for the new flag, and this was unhesitatingly accepted by the six other members of the committee, who voted that the arrangement suggested by the Professor be forthwith adopted. After the episode of the flag, the Professor quickly vanished; and nothing further is known concerning him.

"Did General Washington and Doctor Franklin recognize the Professor as an emissary of the Mystery School which has so long controlled the political destinies of this planet? Benjamin Franklin was a philosopher and a Freemason—possibly a Rosicrucian initiate. He and the Marquis de Lafayette—also a man of mystery—constitute two of the important links in the chain of circumstance that culminated in the establishment of the original thirteen American colonies as a free and independent nation. Dr. Franklin's philosophic attainments are well attested in Poor Richard's Almanac, published by him for many years under the name of Richard Saunders. His interest in the cause of Freemasonry is also shown in his publication of Anderson's Constitutions of 'Freemasonry. "It was during the, evening of July 4, 1776, that the second of these mysterious episodes occurred. In the old State House in Philadelphia, a group of men were gathered for the momentous task of severing the tie between the old country and the new. It was a grave moment, and not a few of those present feared that their lives would be the forfeit for their audacity. In the midst of the debate a fierce voice rang out. The debaters stopped and turned to look upon the stranger. Who was this man who had suddenly appeared in their midst and had transfixed them with his oratory? They had never seen him before, none knew when he had entered; but his tall form and pale face filled them with awe. His voice ringing with a holy zeal, the stranger stirred them to their very souls. His closing words rang. through the building, 'God has given America to be free!' As the stranger sank into a chair exhausted, a wild enthusiasm burst forth. Name after name was placed upon the parchment: the Declaration of Independence was signed. But where was the man who had precipitated the accomplishment of this immortal task—who had lifted for a moment the veil from the eyes of the assemblage and revealed to them a part at least of the great purpose for which the, new nation was conceived? He had disappeared, nor was he ever seen or his identity established. This episode parallels others of a similar kind recorded by ancient historians attendant upon the founding of every new nation. Are they coincidence, or do they indicate that the divine wisdom of the ancient mysteries still is present in the world, serving mankind as it did of old?"

The End

For more on the esoteric history and founding of this nation:

The Mystical George Washington