|

|

||

|

Kitāb Sirr al-asrār (MS A 57) (The Secret of Secrets) ..

Kitāb Sirr

al-asrār

(MS A 57)

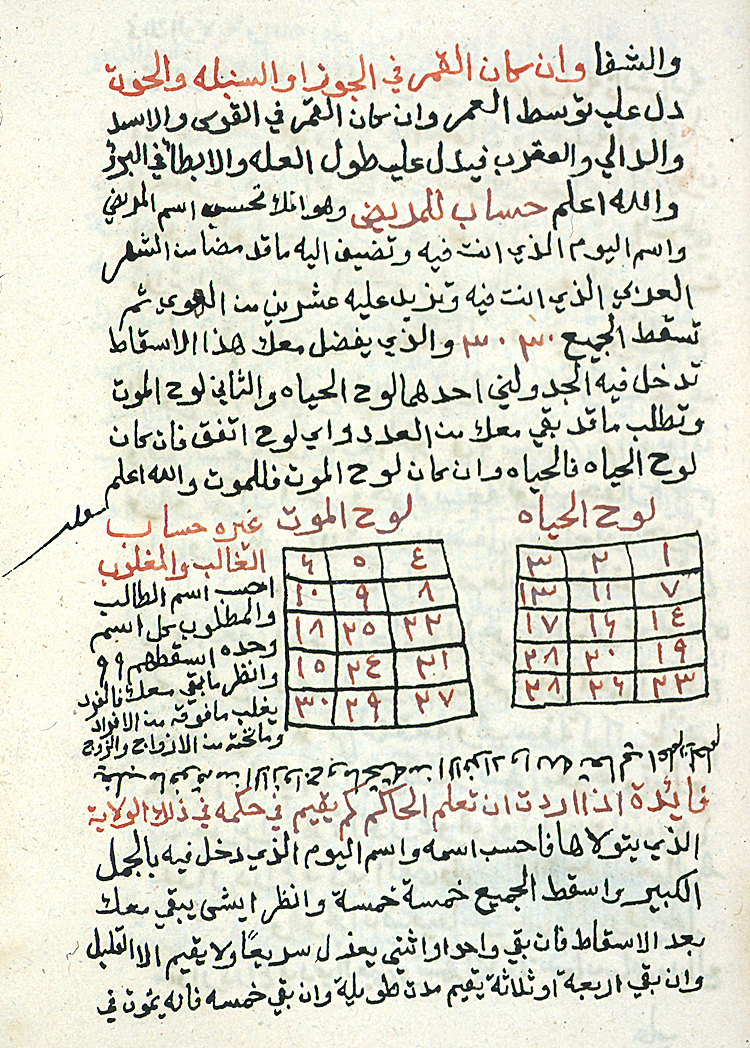

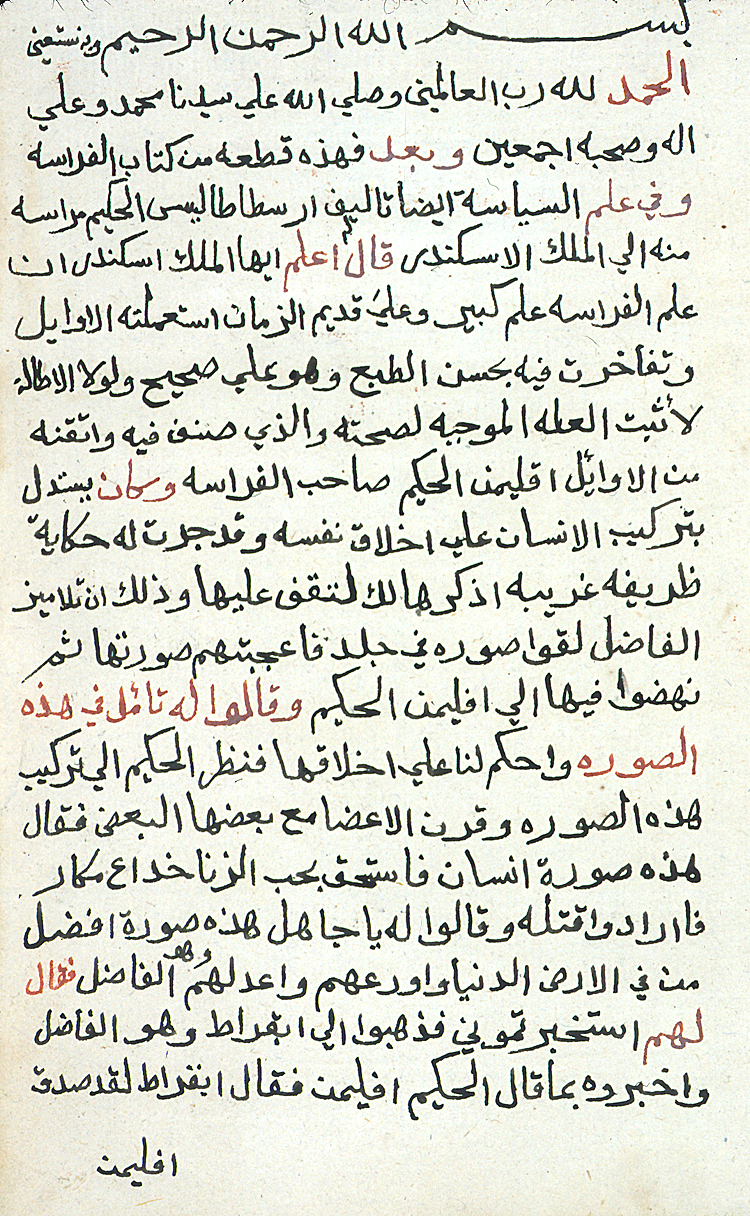

The origins of the treatise are uncertain. No Greek original exists, though there are claims in the Arabic treatise that it was translated from the Greek into Syriac and from Syriac into Arabic by a well-known 9th-century translator, Yahyá ibn Bitriq. It appears, however, that the treatise was actually composed in Arabic. We can with certainty say that the section on physiognomy was circulating in Arabic before AD 940, for there is a manuscript now in the British Library (OIOC, MS Or. 12070) copied in 941/330 by one Muḥammad ibn ‘Alī ibn Durustawayh of Isfahan which contains this particular fragment of the treatise, though it is not called Sirr al-asrār. It antedates all references to the Sirr al-asrār (Secret of Secrets) and is earlier than all other known manuscript copies. It is likely that the treatise now known as The Secret of Secrets gradually evolved over a long period through the accretion of material on a wide range of topics, including statecraft, ethics, physiognomy, astrology, alchemy, magic, and medicine. A Latin translation of the Secret of Secrets from the Arabic was made in the mid-12th century by Joannes Hispalensis (preserved in some 150 copies) and again in the first half of the 13th century by Philippus Tripolitanus (preserved in more than 350 copies). It was extremely influential in Europe, where it was known as the Secretum secretorum and formed the basis of subsequent translations into Czech, Croatian, German, Icelandic, English, Castilian, Catalan, Portuguese, French, and Italian. It was also translated from the Arabic into Hebrew and then into Russian. The Arabic treatise is preserved in two forms: a long version of 10 books and a short version of 7 or 8 books, preserved in a total of about fifty copies. The present manuscript represents one section from the long version. This portion is equivalent to the text found on p. 116, line 17, to p. 124, line, 3, of the edition of the 10-book version of Sirr al-asrār prepared by ‘Abd al Rahman Badawi, Al-Usul al-yunaniyah li-nazariyat al-siyasiyah fī al-islam (Dirasat islamiyah, 15), Cairo 1954. For further discussion of the pseudo-Aristotelian Sirr al-asrar, see: Grignaschi, M., 'L'Origine et les metamorphoses du "Sirr al-asrar"', Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge, vol. 43 (1976), pp. 7-112; Grignaschi, M., 'La Diffusion du "Secretum Secretorum" (Sirr al-asrar) dans l'Europe occidentale', Archives d'histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge, vol. 47 (1980), pp. 7-70; and Mahmoud Manzalaoui, 'The Pseudo-Aristotelian Kitāb Sirr al-asrār: Facts and Problems', Oriens, vol. 23-24, 1974, pp. 146-257. The treatise Kitāb Sirr al-asrār attributed to Aristotle is distinctly different from a treatise on physiognomy with the title Kitāb fi al-firāsah attributed to Aristotle and said to have been translated into Arabic in the 9th century by Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq. For the latter treatise, see Antonella Ghersetti, 'Il Kitab Arsitatalis al-faylasuf fi l-firasa' nella traduzione di Hunayn b Ishaq [Quaderni di Studi Arabi. Studi e testi, 4] (Venice: Herder Editrice,1999). For other copies of Kitāb Sirr al-asrār, see Mahmoud Manzalaoui, 'The Pseudo-Aristotelian Kitāb Sirr al-asrār: Facts and Problems', Oriens, vol. 23-24, 1974, pp. 146-257. SOURCE: Islamic Medical Documents |

||

|

(The Secret of Secrets) Secretum

secretorum is a

medieval treatise also known as

Secret of Secrets, or The Book

of the Secret of Secrets, or in Arabic Kitab

sirr al-asrar,

or the Book of the science of government: on the

good ordering of statecraft.

It is a mid-12th century Latin translation of a 10th

century Arabic encyclopedic

treatise on a wide range of topics including

statecraft, ethics, physiognomy,

astrology, alchemy, magic, and medicine. It was

influential in Europe during

the High Middle Ages.

Origin The origins of the treatise are uncertain. No Greek original exists, though there are claims in the Arabic treatise that it was translated from the Greek into Syriac and from Syriac into Arabic by a well-known 9th century translator, Yahya ibn al-Bitriq. It appears, however, that the treatise was actually composed originally in Arabic. As for its date of origin, we cannot say with certainty whether the section on physiognomy was circulating in Arabic before AD 940: A manuscript now in the British Library (OIOC, MS Or. 12070) supposed to have been copied in 941 by one Muhammad ibn ‘Ali ibn Durustawayh of Isfahan which contains a physiognomy similar to the one in the Sirr al-asrar (Secret of Secrets) is probably a 20th century forgery. More safely, we may assume that a form of the text must have existed after the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-safa' were composed and before the time Ibn Juljul was writing, quite surely in the late 10th century AD. The Arabic version was translated into Persian (at least twice), Ottoman-Turkish (twice), Hebrew (and from Hebrew into Russian), Castilian and Latin. There are two Latin translations from the Arabic, the first one dating from around 1120 by John of Seville for the a Portuguese queen (preserved today in some 150 copies), the second one from circa 1232 by Philippus Tripolitanus (preserved in more than 350 copies), made in the Near East (Antiochia). It is this second Latin version that was translated into English by Robert Copland and printed in 1528. The Latin Secretum secretorum was eventually translated into Czech, Croatian, Dutch, German, Icelandic, English, Castilian, Catalan, Portuguese, French, Italian and Welsh. There is another book called "Kitab al-asrar" (Book of Secrets) on practical technical recipes, classification of mineral substances, description of the alchemical laboratory, etc. by Abu Bakr Muhammed ibn Zakariya al-Razi. A Latin translation appears in Europe as Liber secretorum. This is a completely separate book entirely and is a common source of confusion because of the same names and similar subject matter and time period. In addition it is distinctly different from a treatise on physiognomy with the title Kitab fi al-firasah attributed to Aristotle and said to have been translated into Arabic in the 9th century by Hunayn ibn Ishaq. The Secrets Secrets of Secrets takes the form of a pseudoepigraphical letter supposedly from Aristotle to Alexander the Great during his campaigns in Persia. The text ranged from ethical questions that faced a ruler to astrology and magical/medical properties of plants, gems, numbers, and a strange account of a unified science, of which only a person with the proper moral and intellectual background could discover. An enlarged version appearing in the 13th century includes some alchemical references and an early version of the tabula smaragdina (the Emerald Tablet). The Arabic treatise is preserved in two forms: a long version of 10 books and a short version of 7 or 8 books, preserved in a total of about fifty copies. Influences It was one of the most widely-read texts of the High Middle Ages. Medieval readers took the ascription to Aristotle as authentic and treated this work among Aristotle's genuine works. It was on the medieval "best-seller" list for hundreds of years. Scholarly attention waned around 1550 but lay interest has continued to this day in particular with devotés of the Occult. Scholars today see it as a window onto medieval intellectual life: it was used in a variety of scholarly contexts, and had some part to play in the scholarly controversies of the day. When Roger Bacon found the treatise he believed it was a path to discovery that would yield more divine revelation than a lifetime of study of Albertus or Aquinas. He spent his family's fortune on "secret books and various experiments, and on languages and instruments, and astronomical tables" but the materials that he sought were "difficult and most expensive, for which reason those who know the art ... are not able to operate and the books on that science are so secreted that a man can scarcely find them". Eventually Bacon accomplished little on his own experimentation, depending instead on first-hand accounts from others who had tried. In his quest to discover the secrets from others, he learned from travelers returning from China, of a substance called "blackpowder" and a device "a size as small as the human thumb" packed with this powder produced "a horrible noise" when set on fire. Secret of Secrets was influential in Tudor statecraft. References

|

||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | ||

|

|