|

|

|||

A Hail Cannon is a shock wave generator used to disrupt the formation of hailstones in the atmosphere in their growing phase. An explosive charge of acetylene gas and air is fired in the lower chamber of the machine. As the resulting energy passes through the neck and into the cone it develops into a force that becomes a shockwave. This shockwave, clearly audible as a large whistling sound, then travels at the speed of sound through the cloud formations above, disrupting the growth phase of the hailstones. The device is repeatedly fired every 4 seconds over the period when the storm is approaching and until it has passed through the area. What would otherwise have fallen as hail stones then falls as slush or rain. It is critical that the machine is running during the approach of the storm in order to affect the developing hail stone. These machines can not alter the form of an already developed solidified hailstone. While the history of Hail cannons date back into the 18th century, the modern Hail Cannon has been developed extensively over the last 30 years with most development in the last 10 years. The protected area for an individual machine is approximately a 500 meter radius with a lower level of effectiveness as distance from the device increases. Radar controlled systems are available to replace human operation of the unit which is particularly important in areas subject to hails storms at night. Criticism There is little scientific evidence of the effectiveness of these devices. For example, thunder is a much more powerful sonic wave, and is usually found in the same storm that generates hail, yet doesn't seem to disturb the growth of hailstones. Charles Knight, a cloud physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado says, "I don't find anyone in the scientific community who would validate hail cannons, but there are believers in all sorts of things. It would be very hard to prove they don't work, weather being as unpredictable as it is." Related Links:

|

|||

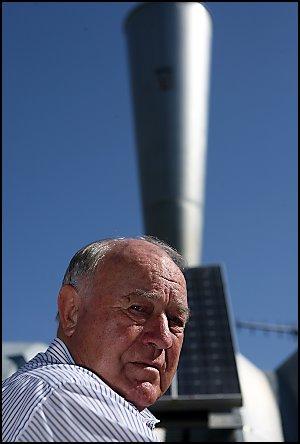

Farmer John Diepersloot has invested between $40,000 and $60,000 in each hail cannon he uses to protect his fruit. by Sasha Khokha

All Things Considered, March 28, 2007 It's spring, and in California's Central Valley, where most of the nation's peaches, plums and almonds grow, orchards are filled with brilliant blooms and tender baby fruit. But sometimes spring hailstorms can destroy that fruit — and farmers there are looking for ways to protect their crops. As Sasha Khokha of member station KQED reports, some of them are putting faith in a very loud device they hope will stop hail from falling out of the clouds. They are shooting booming cannons into the sky, in the hope that the sound waves will break up the ail and turn it into rain. Scientists say there is no way to prove if these cannons really work, but farmers say it is cheaper to try the cannons than to buy hail insurance. SOURCE: NPR |

|||

San Luis Valley split over whether they save crops,

halt rain

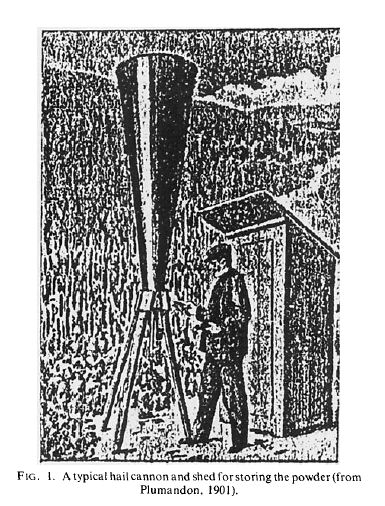

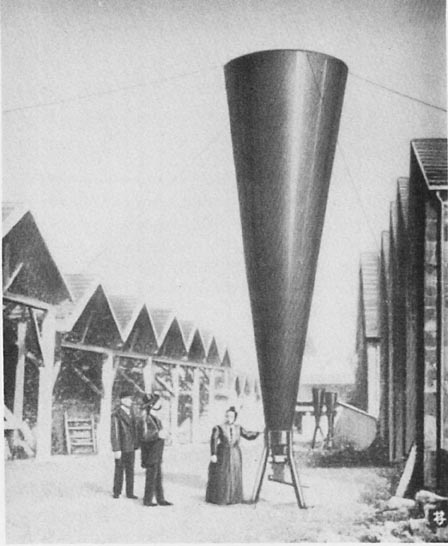

CENTER - Boom. Followed in four seconds by . . . here it comes now . . . boom. Followed in another four seconds by the whistle and thud of another . . . three thousand, four thousand . . . boom. The concussions signal the start of hail season in the San Luis Valley. The reverberations follow blasts from hail cannons deployed around vegetable fields. The theory is that the vibrations from shock waves aimed into approaching storms will disrupt the formation of hailstones that could devastate the crops. "For the last few years, the fields that got hailed on were the fields that were unprotected," said Amy Kunugi, general manager for Southern Colorado Farms. The commercial vegetable grower stirred up bitter feelings this year with its application to renew its state permit to continue operating eight hail cannons. Noise pollution across the vast emptiness of the southern Colorado valley is only one part of the complaint about the hail cannons. More seriously, in a season of worsening drought, ranchers downwind from Southern Colorado Farms believe that the grower's use of sonic cannons to zap potential hail clouds is depriving them of desperately needed rain. "When it affects the rest of us as much as we feel it affects us, that's just not right," said Darell Alexander, a rancher who lives 25 miles northeast of the cannons. "In a time of severe drought, the state should not be licensing a process that decreases precipitation," Alexander said. "I believe big money is talking here, and what little we have is affected." But the sound and the fury may signify nothing. The scientific establishment dismisses the effectiveness of hail cannons, saying that beaming sound waves some five miles into the clouds could not disrupt developing hailstones or steer a rain shower away. So, a two-sided dispute between the growers, who believe the cannons work to prevent hail, and some neighbors, who believe the cannons are denying them rain, becomes a three-sided argument, with scientists contending the hail cannons are just so much noise. In other words, good vibrations are not good science. After all, scientists contend, thunder, which is vastly louder than any sonic wave aimed from earth, would be rumbling in the same storm. The thunder would disturb the growth of hailstones more effectively than a sonic wave. "I don't find anyone in the scientific community who would validate hail cannons, but there are believers in all sorts of things," said Charles Knight, a cloud physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder. Still, he said, "It would be very hard to prove they don't work, weather being as unpredictable as it is." Less bang for the buck Southern Colorado Farms, a multimillion-dollar vegetable grower based in Center, has used hail cannons for more than a decade to protect lettuce, romaine and spinach that are shipped to processors for prepackaged salads. Each of the eight cannons covers a radius of about a third of a mile. The largest such installation in Colorado, the eight cannons provide a form of insurance, since affordable crop insurance is not available, that the 2,400 acres will not be lashed by hailstones and the $12 million crop destroyed. Still, Mike Jones, the grower's controller, acknowledged that the company doesn't have science on its side. "We admit there's no hard science to substantiate that they work, partly because no studies have been done on it," Jones said. "But we don't have any second thoughts about operating them because we don't believe they have any harmful effects." The cannons were used seven times during the 2005 growing season, with an average duration of 1 hour and 20 minutes, compared with 12 uses with an average duration of 52 minutes in 2004, according to the grower. The cannons, which resound like blasts from Fourth of July fireworks up close, are muffled by straw bales stacked around the barrels to absorb the sound even though the nearest homes are at least a quarter-mile away. At that distance, or farther, protesters compare the noise to a diesel truck. In effect, the muffling gives less bang for the buck although ranchers 10, 15 or more miles across the valley hear the concussions. "They are boom . . . boom . . . boom. Repetitive," said Virginia Sutherland, a cattle rancher near Saguache. "You can't compare the hail cannons noise to traffic noise because traffic noise is steady," said Howard McGregor, president of Engineering Dynamics Inc., an Englewood firm that has measured decibel levels for the grower. McGregor described the sounds from the hail cannons as "impulsive" and "of short duration." The dispute over hail cannons has stirred up small-town resentments, awakened political partisanship, called into question values held sacred by family farms and ranches, and provoked renewed controversy over whether modifying weather is playing God in the driest part of the state. Like many tales from the arid West, the dispute began with water. Provoking Mother Nature In a good year, the San Luis Valley receives only 7 or 8 inches of precipitation, about half what Denver gets, said Nolan Doesken, assistant state climatologist. But, this has not been a good year. The valley has received only about 5 inches of precipitation in the past 12 months, he said. Snowpack in the mountains that border the valley was not much better, with only 64 percent of average snow depth April 1, said Mike Gillespie of the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Since 2000, snowpack has measured average or higher only twice and markedly below average the other years, he said. The result is that the valley, the sunniest and driest part of Colorado, is wrenched by drought, the kind of drought that sends haggard farmers to visit their bankers, hat in hand. "You are in an area experiencing drought," Doesken said as dirt swirled from the fields around Center, where he was meeting with area residents. "It's significant drought, getting worse as we speak." Still, the stark beauty of the valley attracts people who want to live at one with nature. The valley is a mindset as much as a place, a vast geologic bowl caressed by the Sangre de Cristo mountains on the east and the San Juan mountains on the west. Ranchers, living miles across the valley, blame Southern Colorado Farms for more than just diverting storms headed their way. Besides the concussions, they report strange wind patterns after the cannons are fired. They say the cannons leave an odd odor in the air and an unusual taste in the mouth. In the small-town way that disagreements can fester into intensely personal disputes, protesters have vented their anger on John Smith, a lawyer, banker and former Alamosa County district attorney, who is the principal owner of Southern Colorado Farms. His image as a liberal Democrat in Republican rural Colorado sets him at odds with some neighbors, who label him a town farmer. "I think it's resentment," Smith said. "Having no other place to vent their frustrations about the drought, they have directed it at me." Some of Smith's neighboring vegetable growers at Center, Richard Noe and Jack Kuntz among them, supported the farm's application for a renewed permit to operate the hail cannons for this growing season. "We do believe hail cannons soften the hail, but do not stop the rain," Noe said in a letter supporting Smith's application. But, opponents of the cannons outnumbered advocates at a public meeting on the reapplication process. "Nobody should play God with the weather," said Lynn Sutherland, who ranches with her mother Virginia Sutherland. "It's not something that anyone, licensed by the state of Colorado or otherwise, should do." History of Hail Cannons Hail cannons have been in use for centuries and debunked just as long. By the mid-19th century, Italians were firing small, specially made cannons filled with gunpowder at clouds that threatened to hail on their orchards and vineyards. The October 1919 edition of Popular Science magazine had a cover story on "Hail Fighters and Their Strange Devices," complete with an illustration of cannon barrels pointed skyward. "By 1919, hail cannons had been discredited, but people intent on changing the weather refuse to give them up," the magazine headlined almost 90 years ago. Today, Mike Eggers Ltd., based in New Zealand, is the principal manufacturer of hail cannons used in the United States for "horticultural protection." The sticker price is $50,000 a unit to provide coverage over a radius of one-third of a mile, would-be purchasers said. Eggers declined to talk price. Ultimately, Eggers is selling hope, which history has shown is more potent than any cannon, especially one that resembles a prop for a grade-B movie about invaders from outer space. In Eggers' sales information, the hail cannons are held out to disrupt "the formation process of the hailstone embryo," not to break up hailstones that already have formed. However, even Eggers conceded that there "has been no scientific program to evaluate whether they work." However, farmers have been buying them to protect their crops, from vegetables to pecans. Operating hail cannons becomes the meteorological equivalent of eating an apple a day to keep the doctor away: The cannons may just do some good. Among vegetable growers on the northern Front Range, Glen Fritzler operates two hail cannons and his neighbor Dave Petrocco uses two. "All my neighbors seem glad to have the hail cannons nearby," Petrocco said. "They are not 100 percent, but they do help significantly." Fritzler said he knows the cannons have a reputation for being ineffective. "Nobody makes fun of me for using them," he said, "but they may be saying things behind my back." Beyond agriculture, Nissan has bought two hail cannons, which it prefers to call hail-suppression vehicles, to protect new cars awaiting shipment from a factory at Canton, Miss. "You might hoodwink these people once, but you won't hoodwink them for 10 years," Eggers said, speaking specifically about Southern Colorado Farms. But scientists said hail cannons are weather voodoo. The question may be who is hoodwinking whom. "No one who manufactures them can provide scientific information about how they work," said Bruce Boe, director of meteorology with Fargo, N.D.-based Weather Modification Inc. "The hail cannon is comforting the owner because he believes it's doing some good. The boom may be disturbing some people, but people don't need to be worried about it depriving them of rain because it's not. "It's just making a loud noise." Striking a Compromise While reissuing a weather modification permit to Southern Colorado Farms for the current growing season, the Colorado Water Conservation Board also asked the grower and its neighbors to collect weather data and videotapes of storms. Before issuing the grower a permit to use the hail cannons next summer, the board plans to call a fall meeting to begin to evaluate the weather data for hard evidence about their effectiveness. Both Southern Colorado Farms and the protesters have a measured victory. The grower continues to use the hail cannons, although with only a one-year permit, not the five-year permit it had sought. "It's a step in the right direction to get more people aware of what's going on here," said Thad Englert, a rancher at Moffat who raised questions about the hail cannons. "The real necessity is to find out whether weather modification is hampering precipitation in the valley." garnerj@RockyMountainNews.com or 303-892-5421 SOURCE: Rocky Mountain News |

|||

History Repeated: The Forgotten

Hail Cannons of Europe

History

Repeated: The Forgotten Hail Cannons of Europe (PDF)

|

|||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |||

|

|