|

Craters Galore |

|||

|

..

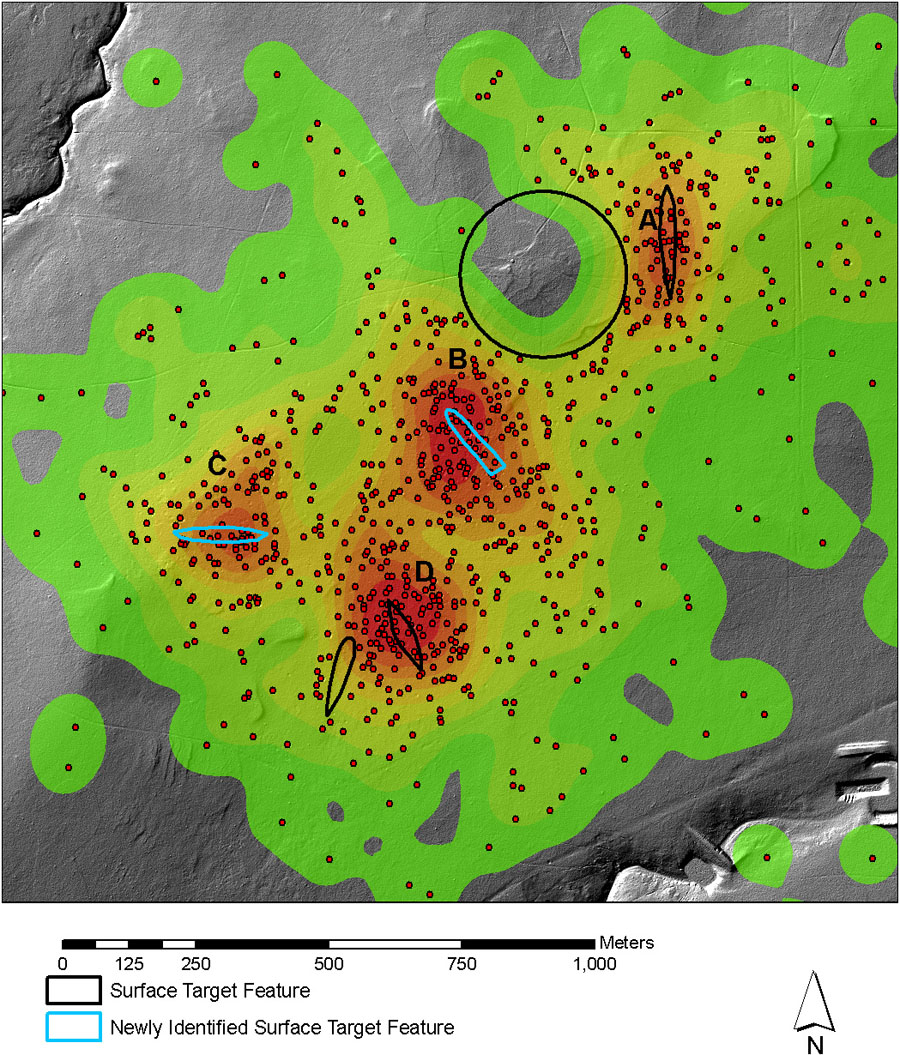

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. —It’s a local twist to a nationwide problem: Potential unexploded ordnance (UXO) at old bombing ranges. A complete site survey was conducted at the old Kirtland bombing range near Double Eagle Airport on Albuquerque’s west mesa recently by a team from Sandia National Laboratories and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). The survey was part of an expansion of the Eclipse Aviation facility near Double Eagle Airport for installation of water and power lines. The survey of the Kirtland site, one of the national Wide Area Assessment (WAA) sites, was initiated and funded by the Department of Defense’s Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP) and the Environmental Security Technology Certification Program (ESTCP). |

|||

|

..

Both high-resolution, color orthophotography and LiDAR data were collected simultaneously at Edwards in January 2006. The LiDAR data was used to create a high-resolution, bare-earth, digital elevation model which allowed analysts to identify micro-topographic munitions-related features such as bomb craters, target berms, etc. The orthophotography was used for direct detection and visualization of potential munitions related features, as well as discrimination of LiDAR features that were not munitions related. These two datasets were used together during the WAA analysis. |

|||

| 50 years ago:

A bomber accidentally dropped its cargo near Albuquerque

Albuquerque

Tribune

A flash in the sky, a boom, a mushroom-shaped cloud rising to the south of Albuquerque. If we lived in a parallel universe where the Department of Energy didn't use safety precautions on nuclear weapons - and that's a pretty big "what if" - then 50 years ago Tuesday could well have marked the end of the Duke City. On that date, May 22, 1957, a B-36 bomber carrying a nuclear weapon accidentally dropped its cargo about 4 miles south of the control tower at Kirtland Air Force Base. The plane was carrying the weapon from Biggs Air Force Base in Texas to Kirtland for maintenance, said Gerry Taylor, 81, a former Manhattan Project scientist who works as a docent at the National Atomic Museum. "In that era, the main storage area for the hydrogen bomb was an air base in San Antonio," Taylor said. "They had to come back to Albuquerque once a year for modification and to keep them up to date." As was usual procedure, the plutonium pit of the weapon had been removed for transport, although the pit was still on the plane. And as usual, the bomb was designed not to explode on impact, but rather through a signal from a trigger device, said Dave Jackson, 73, former director of public affairs for the Department of Energy in Albuquerque. "It could not, under any circumstances, have produced a nuclear detonation," Jackson said. Still, the bomb accidentally fell during landing. It slipped loose in a standard procedure designed to keep flyers safe, Taylor said. "The parachute on the bomb opened, and the control tower asked the pilot `Do you have hot cargo aboard?' " Taylor said. "He said, `Not anymore, I lost it back there.' " In the parallel universe, everything after that conversation would have been dramatically different. In the parallel universe, the bomb - a 10 megaton Mark 17 - would have vaporized everything in the immediate area in a massive, 1,000-foot-high fireball, said Greg Mello, executive director of the Los Alamos Study Group, an anti-nuclear weapons organization. "That's a big bomb," Mello said. "That would make a huge crater hundreds of feet deep and would throw up an enormous amount of fallout." The blast would have flattened buildings within a radius of a few miles - so the control tower would likely still be standing, Taylor said. "The immediate area of the detonation would turn to glass - about the size of a football field - but the explosion probably wouldn't have torn any buildings up," Taylor said. "It wasn't that powerful. The bomb we dropped on Japan only destroyed 1.6 miles of buildings." But other byproducts of the explosion would create a significant disaster, Mello said. The control tower most likely would have quickly been engulfed in a massive fire, Mello said. "If you can see the fireball, then that heat shines even beyond the blast radius through windows in buildings and ignites things," Mello said. "Anyone in the open would be burned and many buildings would be on fire." A lethal surge cloud would have spread out into southern parts of the city, and dirt and debris contaminated with a radioactive stew of strontium, cesium and iodine would have settled across the landscape, Mello said. "There's a low-level cloud and also a high-level cloud that would have gone across several states with diminishing mortality and morbidity downwind," Mello said. The death toll would be in the tens of thousands and the city would have been contaminated for centuries, he said. "Abandonment becomes a very real possibility," Mello said. "This is different than the bombs dropped on Japan. They exploded in the air, but the fireball never touched the ground. This would have touched the ground." The bomb's interaction with the ground is what causes fallout. Dirt is pitched up in the air and mixes with the radionuclides, then falls back to the earth and blows around. The Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs went off in the air, so there was technically no fallout, Mello said. Albuquerque - even with its rich history and cultures - would simply not have been worth rebuilding, Mello said. "Instead of the Land of Enchantment we'd be the Land of Entombment or something," he said. Fortunately, however, we don't live in that parallel universe, Mello said. And in reality when the bomb fell, only the conventional explosives inside it went off, and a small amount of plutonium was spread on the ground, Taylor said. The explosion created a crater about 6 feet deep and 25 feet wide. "It wasn't nuclear, but there was some radiation," Taylor said. "All the radiation stayed in the crater." Recovery teams from Kirtland, Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratory quickly cleaned up the area and removed bomb debris from the site and the crater was plugged with concrete. "To Sandia's credit, they did a good job," Mello said. Nobody died or was seriously hurt - except, perhaps, for a few desert critters, Jackson said. "There might have been a jack rabbit out there, but nobody knows," Jackson said. |

|||

| April 11, 1950

A B-29 Bomber carrying a nuclear bomb crashes into a mountain on Manzano Base near Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. The bomb is destroyed but the accompanying nuclear capsule, which had not been inserted into bomb, remains intact. May 22, 1957 A B-36 ferrying a nuclear weapon from Biggs Air Force Base, Texas to Kirtland accidentally discharges a bomb in the New Mexico desert. The high explosive material detonates, completely destroying the weapon and making a crater approximately 25 ft in diameter and 12 ft deep. Radiological survey of the area disclosed no radioactivity beyond the lip of the crater at which point the level was 0.5 milliroentgens. The nuclear capsules had not been inserted into the bombs. A nuclear detonation was not possible. - SOURCE |

|||

Weapons Display Area (WDA)

The Defense Threat Reduction Agency maintains a large collection of nuclear weapons displays, systems and components at the Defense Nuclear Weapons School (DNWS), Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico. The Weapons Display Area (WDA) is an integral part of courses taught at the DNWS, providing students a unique opportunity to see, first hand, the evolution of nuclear weapons technology and to apply the concepts developed in the classroom. In addition to its prominent role in training, the WDA not only benefits the DOD but is used by the DOE as well. It provides the National Laboratories, and the nuclear community as a whole, with an opportunity to study the design features associated with each weapon. The WDA is a unique national treasure. It is the most complete comprehensive collection of its kind, tracing the entire evolution of U.S. Nuclear Weapons from the Little Boy and Fat Man, all the way to the most current stockpiled weapon. This collection is not open to the general public.

However, even with this constraint, a yearly average of 2,200 individuals

tour the facility. Those requiring information should contact the Defense

Nuclear Weapons School, General Information and Customer Support: dnws@ao.dtra.mil

|

|||

|

..

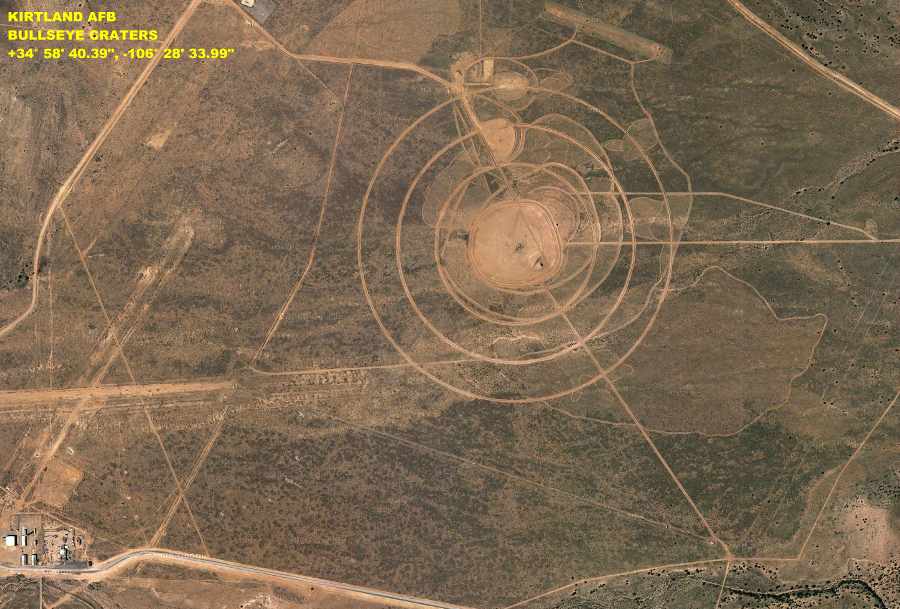

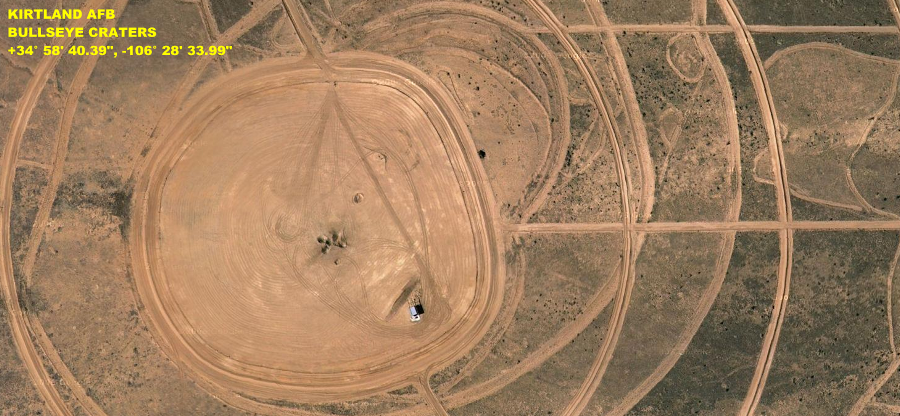

This is one of the many bomb craters in the vicinity of Kirtland AFB. The southern end is now being developed for housing, causing a renewed effort to hunt down and dig up unexploded ordinance... The whole are is riddled with craters of various size, but the most striking thing about the area is the spidery lines created by the blasts, unlike a meteorite impact which throws rays of ejecta around the rim of a crater, these lines are cracks in the Earth itself and go for several miles... just look around the are on Google Earth and you will see the effect. In the image below you can see one of the craters that

has filled with water. Many of these are used by ranchers as watering holes

for cattle and you will see corals in the crater vicinity..

|

|||

|

..

|

|||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |||

|

|