|

The Lost Cosmonauts |

||||||||||||||

|

July 2008

What really happened to Russia's

missing cosmonauts? An incredible tale of space hacking, espionage and

death in the lonely reaches of space.

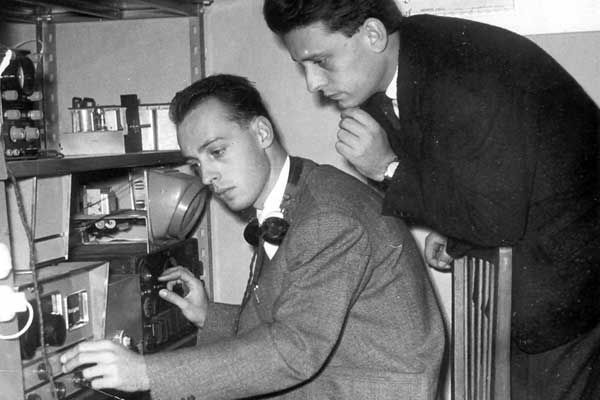

FT233 Midnight, 19 May 1961. A crisp frost had descended on Turin’s city centre which was deserted and deathly silent. Well, almost. Two brothers, aged 20 and 23, raced through the grid-like streets (that would later be made famous by the film The Italian Job) in a tiny Fiat 600, which screamed in protest as they bounced across one cobbled piazza after another at top speed. The Fiat was loaded with dozens of iron pipes and aluminium sheets which poked out of windows and were strapped to the roof. The car screeched to a halt outside the city’s tallest block of flats. Grabbing their assorted pipes, along with a large toolbox, the two brothers ran up the stairs to the rooftop. Moments later, the city’s silence was rudely broken once more as they set to work: a concerto of hammering, clattering, sawing and shouting. Suddenly, an angry voice rang out; the man who lived on the floor below leant out of the window and screamed: “Will you stop that racket, I’m trying to sleep!” One of the young men shouted back “Sorry sir; the Soviets have launched a satellite and we’re trying to intercept it!” The brothers finished setting up, grabbed their head-sets, twiddled the knobs on their portable receivers, hit the record button and listened… “Come in… come in… come in… Listen! Come in! Talk to

me! I am hot! I am hot! Come in! What? Forty-five? What? Fifty? Yes. Yes,

yes, breathing. Oxygen, oxygen… I am hot. This… isn’t this dangerous?”

“Transmission begins now. Forty-one. Yes, I feel hot. I feel hot, it’s all… it’s all hot. I can see a flame! I can see a flame! I can see a flame! Thirty-two… thirty-two. Am I going to crash? Yes, yes I feel hot… I am listening, I feel hot, I will re-enter. I’m hot!” The signal went dead.

Credit: Alex Tomlinson FROM OUTER SPACE There are those who believe that somewhere in the vast blackness of space, about nine billion miles from the Sun, the first human is about to cross the boundary of our Solar System into interstellar space. His body, perfectly preserved, is frozen at –270 degrees C (–454ºF); his tiny capsule has been silently sailing away from the Earth at 18,000 mph (29,000km/h) for the last 45 years. He is the original lost cosmonaut, whose rocket went up and, instead of coming back down, just kept on going. It is the ultimate in Cold War legends: that at the dawn of the Space Age, in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s, the Soviet Union had two space programmes, one a public programme, the other a ‘black’ one, in which far more daring and sometimes downright suicidal missions were attempted. It was assumed that Russia’s Black Ops, if they existed at all, would remain secret forever. The ‘Lost Cosmonauts’ debate has been reawakened thanks to a new investigation into the efforts of two ingenious, radio-mad young Italian brothers who, starting in 1957, hacked into both Russia’s and NASA’s space programmes – so effectively that the Russians, it seems, may have wanted them dead. The brothers’ passion for radio began in 1949, when Achille Judica-Cordiglia was 16 and Gian was just 10. For them, radio was the Internet of its day, a wonderful invention which fuelled their dreams of exploration; they adored cinema too, and filmed everything they did. More than 50 years ago, on 4 October 1957, an event took place that transformed their lives forever. The brothers were sitting at a table in the large attic bedroom where they should have been doing their homework but, as usual, were tinkering with old radio parts. Suddenly, the programme they were listening to was interrupted – the Soviets had just launched Sputnik I (left), the first satellite to orbit the Earth. “They gave the frequency it was transmitting its beeps on,” recalled Achille, “so we thought: shall we try?” They didn’t know it, but Turin was perfectly situated to track the Soviet satellites; northern Italy was the only area in Western Europe on Russia’s orbital path. The brothers had their recording within a few minutes. Elated, they decided that they would track and record anything that went up into space. The brothers ended up constructing an 8m (26ft) collapsible dish which they sneakily perched on the rooftop of the highest block of flats in Turin’s city centre. To try and keep it secret they built it in such a way that it could be erected and dismantled extremely quickly. After the success of Sputnik, Russian Premier Nikita Khrushchev boasted: “The US doesn’t have an intercontinental missile; otherwise, it would have easily launched a satellite of its own.” Russia had demonstrated that it had the power to fire its nuclear weapons to anywhere in the US. Space was about to become the major battleground of the Cold War, and the Judica-Cordiglia brothers dreamed of being part of it. The brothers went on to record the first living creature in space the following month, when Laika the dog travelled aboard Sputnik 2, and then, in February 1958, the beeps from Explorer 1, America’s first satellite. Younger sister Maria Teresa recalled “being in their room was like being in the workshop of Dædalus, it was brimming with ideas… it was one big adventure.” Then, on 28 November 1960, the Bochum space observatory

in West Germany said it had intercepted radio signals which it thought

might have been a satellite. No official announcement had been made of

any launch.

“It was a signal we recognised immediately as Morse code – SOS,” said Gian. But something about this signal was strange. It was moving slowly, as if the craft was not orbiting but was at a single point and slowly moving away from the Earth. The SOS faded into distant space. The story was picked up by a Swiss-Italian radio station, and the brothers became the station’s space experts. By now, the Judica-Cordiglias were more than ready to capture the first human sounds from space. They came sooner than expected. At 10.55pm on 2 February 1961, the brothers were scanning Russian frequencies as usual when Achille picked up a transmission from an orbiting capsule. They recorded the wheezing, struggling breathing of what they thought was a suffocating cosmonaut. The brothers contacted Professor Achille Dogliotti, Italy’s leading cardiologist and recorded his judgement. “I could quite clearly distinguish the clear sounds of forced, panting human breath,” said Dogliotti. Two days later, the Soviet press agency announced that Russia had sent a seven-and-a-half-tonne spaceship the size of a single-decker bus into space on 2 February, which had burned up during re-entry. No further information was forthcoming. Had the brothers captured the dying breaths of a cosmonaut?

Credit: Alex Tomlinson AIRBRUSHED FROM HISTORY James Oberg worked in NASA’s mission control for almost 20 years before becoming a space historian specializing in the Russian space programme. According to him, “the sounds the Judica-Cordiglias heard could be interpreted to mean a lost cosmonaut; in those days nobody could tell. In those days so much was secret and much of the Soviet space programme was wrapped in disinformation, and bred by ignorance.” Large parts of the early Soviet Space programme remain unknown to this day; information was destroyed; most of those involved have died or vanished. Some historians have recently solved some of the mysteries surrounding the early cosmonauts. Oberg himself discovered that a famous photo of the ‘Sochi Six’, a group of Russia’s original top cosmonaut candidates, had been doctored, erasing one of the six men. Oberg discovered that the rosebush was Grigoriy Nelyubov, expelled from the programme in 1961 after a drunken brawl with some soldiers. Some time later, drunk and depressed, Nelyubov stepped in front of a train and was killed. Other airbrushings include Anatoliy Kartashov, who experienced skin bleeding during a centrifuge run, and Valentin Varlamov who vanished after injuring his neck in a diving accident. Vladimir Shatalov, the Commander of Cosmonaut Training from 1971 to 1987, admitted that “six or eight” trainees had died in the 1960s, but wouldn’t say how. The Russian cosmonaut, it seems, had to be perfect or not exist at all. By 1971, nine cosmonauts had vanished from the official photographs which were re-released in honour of the 10th anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s flight.

Credit: Alex Tomlinson ..

Credit: Alex Tomlinson So, did any cosmonauts actually die in space? Russian journalist and 1965 cosmonaut candidate Yaroslav Golovanov claimed that on 10 November 1960, a cosmonaut called Byelokonyev died on board a spaceship in orbit. Mikhail Rudenko, a retired senior space engineer, claimed a few years ago that three early victims were test pilots who were simply blasted straight up into space between 1957 and 1959. Sadly, there is no evidence to back these claims. But the Soviets were experts at making people and evidence disappear, so it is all too easy to believe that more deaths might have occurred in those desperate early days of the space race. Risks were taken at the insistence of Khrushchev, who needed results for political leverage. Tests were not completed and safety checks were ignored. On 23 October 1960, a rocket exploded at Baikonur vaporising 165 technicians, an event that was hushed up by the Soviet authorities for over 30 years. One fatality that we do know about from those early days was that of Valentin Bondarenko. At 24, he was the youngest cosmonaut. He met his terrible end on 23 March 1961, while in a pressure chamber as part of a 10-day isolation exercise. Bondarenko dropped an alcohol-soaked cotton swab on a hot plate, which – in the oxygen-rich environment – started a fire that ignited his suit. It was 20 minutes before the pressurised door could be opened. Bondarenko was pulled out barely alive, crying “It was my fault”, and died eight hours later, comforted by his best friend, Yuri Gagarin. News of the accident was hushed up until 1986. Two weeks after Bondarenko’s death, on 11 April 1961, an Italian journalist working for the International Press Agency in Moscow received a tip-off that something “of immense importance” was about to happen. He called the Cordiglia brothers. “We leapt out of bed,” said Achille, “dashed over to our receivers and began listening. Suddenly, in what was a magical moment, the hiss faded and this Russian voice emerged from very far away for a few seconds.” At that stage, no one in the West – not even the President of the United States – knew that the Russians had launched a rocket. Russian translators were few and far between but the brothers had this covered – their younger sister was fluent in Russian. The first sentence they heard was: “The flight is proceeding normally. I feel well. The flight is normal. I am withstanding well the state of weightlessness.” As the brothers listened, the cosmonaut experimented

with zero gravity. They lost the signal as the cosmonaut prepared for re-entry

while whistling a communist hymn. It was only then that President John

F Kennedy was awoken at 2am to be given the news that Yuri Gagarin was

the first man in space.

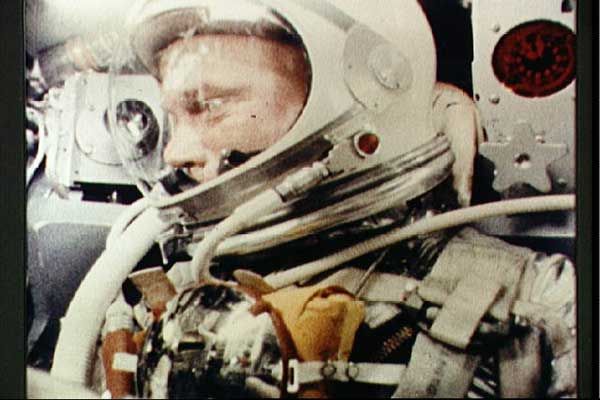

Credit: Alex Tomlinson TORRE BERT The brothers got permission to take over a disused German bunker on the outskirts of Turin at a place called Torre Bert. Reclaiming all the scrap metal and old pipes they could find, they enlisted the help of a dozen student volunteers and constructed a series of antennæ, eventually creating a super-dish with a diameter of 15m (50ft) and weighing one and a half tonnes. The brothers stuck a sign on the bunker wall: Torre Bert Space Centre. Inside, using discarded WWII American army equipment, they created an exact replica of Cape Canaveral, including an enormous map of the world behind a Perspex sheet along with an LED display that marked satellites’ progress. Kitchen clocks provided the time in London, Moscow, Cape Kennedy and Turin. Volunteers wore white coats. While the US spent 15 million dollars on one listening post, Torre Bert had cost the brothers nothing; and, as they soon discovered, it worked just as well. With the opening of Torre Bert, the Judica-Cordiglia brothers became local superstars. “Those days were frenetic and exciting,” recalled Gian’s wife Laura, “because when word got out that there was a space mission it was packed with girlfriends, friends, students; even professors started coming.” The brothers found partners to create their own amateur space-tracking network, dubbed ‘Zeus’. When they got word of an imminent launch, they notified 16 stations across the world. Gian’s fiancée coordinated the operation. The Americans were due to put a man into space on 20 February 1962, 10 months after Gagarin. The Judica-Cordiglia brothers were desperate to listen in, but NASA kept the wavelength secret for fear of Soviet interference. “We came across a photograph of an unmanned NASA Mercury capsule being recovered from the ocean,” said Gian. John Glenn was going to fly in the same craft. In the photograph they could see the antenna. “If we could accurately determine the length of this antenna then we’d have the frequency.” But the brothers lacked a scale. They told their father, a lecturer in legal medicine at Milan University, who had a solution. In the picture, four frogmen were sitting in a boat. He used the bizygomatic index – the distance between the right and left cheek bones in proportion to the width of the face – to calculate what 1cm (0.4in) represented on the photograph. “It seemed so simple but no one else had thought of it. Somehow, we’d managed to crack America’s top secret!” Achille said. On 20 February1962, while John Glenn lay flat on his back inside the instrument-packed capsule Friendship 7, a buzzing Torre Bert was packed full of students, professors, children, friends, family, hangers-on and one or two shady characters (of which, more later). For several long minutes, static streamed into Torre Bert, when suddenly Achille hissed “SSSSSSHH!” And then it came through: the voice of the first American in space: “Capsule is turning around. Oh, that view is tremendous! I can see the booster doing turnarounds just a couple of hundred yards behind. Cape is go and I am go.” They listened as Glenn gobbled malt tablets, squeezed a tube of apple sauce into his mouth and told ground control he felt fine. “I have had no ill effects at all from zero G. It’s very pleasant, as a matter of fact. Visual acuity is still excellent. No astigmatic effects. No nausea or discomfort whatsoever.” Then Friendship 7 shuddered. Glenn’s body was squeezed by G-force. A fiery glow enveloped the ship as he began re-entry. Cape Canaveral lost radio contact. So did the Judica-Cordiglias.

For Cape Canaveral, the silence lasted for seven minutes. Then came Glenn’s

exultant voice. “Boy!” he cried. “That was a real fireball!”

As every computer hacker knows, finding out secrets can be dangerous – but the risk is what makes the game so thrilling. That risk was about to catch up with the Cordiglias.

Image courtesy of Judica-Cordiglia brothers. Credit: Alex Tomlinson THE GUARDIAN ANGEL A few days later, the Judica-Cordiglias’ doorbell rang. Standing there like a character straight from a spy movie was a serious-looking, swarthy man in a long coat with a heavy Russian accent. He said he was a journalist. The brothers gave him an interview. Shortly after the Russian ‘reporter’ left, the doorbell rang again. This time it was a short Italian man with a neat beard in a smart suit. He pulled a photo out of his pocket. It was of the Russian ‘reporter’. “This man is not just a journalist; he works for the KGB, so beware. I work for SIFA [the Italian Secret Service], counter intelligence,” he said. “Know that we are looking after you. But be careful,” he warned them. “We can’t be everywhere.” And he left. The brothers later became firm friends with this man they called their “guardian angel”. I was told by a retired journalist that the same KGB agent eventually became a Russian ambassador to a European country. Armed with a name, I tracked him down in the Czech Republic. He agreed to meet me in the art-deco basement bar of Prague’s extraordinarily ornate Municipal House. Sitting amongst the tourist hubbub, speaking to me on condition of anonymity, he told me a tale from 50 years ago, a time when Eastern Europe was a very different place: “Of course we were interested in the Judica-Cordiglia brothers; they were hacking into our communications. Imagine that today; a pair of amateur kids taking apart the Russian space programme like it was a toy. “I heard the Gagarin recording, transcribed it and verified it was genuine. Our cosmonauts were warned to be careful what they said while in space after this and we had the brothers followed.” I next tracked down the brothers’ “guardian angel”, who insisted that his name and location be kept secret. “When the Judica-Cordiglia brothers were approached by the Soviets,” he told me, “we immediately decided to make contact with them. Our goal was to protect them but also to obtain information about Soviet spacecraft. At first they didn’t trust me, but soon we became friends.” The brothers didn’t realise how much danger they faced. The retired KGB agent had told me: “They had to be dealt with – an accident perhaps – but then that TV programme happened and they were famous. That saved their lives. I was glad; they were good kids.”

Image courtesy of Judica-Cordiglia brothers. Credit: Alex Tomlinson THE FAIR OF DREAMS The telephone call that may well have saved their lives came from Mike Bongiorno, Italy’s most popular TV presenter who told them: “I want you to come on my quiz show Fiera dei Sogni [The Fair of Dreams], and if you win I’ll make your dreams come true.” For the Judica-Cordiglias, their dream was to visit NASA, something they thought was way beyond their reach, but now they had a chance. The only catch was that they had to win Italy’s most popular and toughest TV quiz, the Italian equivalent of Mastermind. Contestants had to answer questions on their specialist subject within a certain time frame; incredibly, the brothers answered every single question correctly, and in record time. They arrived in the US on 26 February 1964. They filmed

everything. First stop was the huge white building that was NASA headquarters

in Washington. Waiting for them on the top floor was John Haussman from

Tracking and Data Acquisition. He wasn’t looking forward to babysitting

two space-mad Italians.

“How did you get this?” Haussman demanded, “It’s not possible!” He phoned a colleague. “You’ve gotta come and hear this.” James Morrison, NASA’s Space Programmes Technical Director arrived minutes later. “I’ll be darned!” he exclaimed. “How did you do this?!” Turning to Haussman, he said, “We should be more careful; if they intercepted it so can the Russians.” A few minutes later the room was packed and the two boys found themselves discussing orbits with America’s top scientists – their dreams really had come true. The next part of their story has remained secret to this day. Many sceptics have argued that it was impossible for the brothers to have listened into so many Russian space missions. It may be, as some have claimed, that the brothers sometimes felt under pressure to produce results and were tempted to satisfy the insatiable popular demand for space stories by fabricating sensational new recordings. It’s unlikely, for example, that the soft beating sounds they once recorded were really a cosmonaut’s heartbeat as they claimed; heartbeats were broadcast from the capsules, but as electrical signals which sounded like static. But it’s also true that the Russians always made every effort to keep their disasters secret. In April 1967, Vladimir Komarov died when Soyuz 1 crashed on re-entry due to a design fault. His ship was a prototype of the one Russia hoped to send to the Moon, but had been plagued with major design problems from the start. Not wishing to reveal their mistake, the Russians said that Komarov’s parachute had simply failed on re-entry. Some accounts suggest that the Bochum tracking station, part of the Zeus network, overheard Komarov cursing the ship’s designers while he was still in orbit. Experts now accept that the brothers did record some Russian and American space missions, but that their interpretations weren’t always accurate. NASA knew exactly what they had accomplished back in 1964 and wanted all their information. But the brothers wanted something in exchange: “We were missing two frequencies used by the Soviets and we wanted to know if NASA had them. The problem was that NASA didn’t really trust us!” Eventually, they decided on a straightforward swap. In total silence they began passing pieces of paper back and forth. Achille recalled: “When I finished writing the first frequency, Haussman said to me with a half smile: ‘Correct.’” “Now,” Gian said, “it’s our turn.” The man handed them a piece of paper. “I was disappointed because we already had that one.” NASA didn’t have the next two frequencies that the Judica-Cordiglias gave them. NASA Director Harry J Goett told them: “You guys have done a remarkable job.” “Then, when NASA gave us the third and fourth frequencies, they were totally new!” said Gian. “We shook hands and then practically ran from the building.” The brothers bear-hugged and danced in the street out of sheer joy at what they had accomplished. Once they arrived back in Turin, they found Torre Bert besieged by fans, enthusiasts – and spies from both sides who had started hanging around. Every now and again, their “guardian angel” appeared to tell the brothers just who these sinister characters were. Documents went missing, including some blurry pictures of the Moon transmitted from the Soviet Lunik 4 probe. “But we’d already sent copies to the papers,” said Gian, “so it didn’t matter.” Despite threats from the KGB, the Judica-Cordiglia brothers continued. They captured the final mission of the Vostok spacecraft by the female cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova and the first-ever spacewalk, taken by Aleksei Leonov in March 1965. Afterwards, when Leonov tried to climb back into the airlock, he found that his spacesuit had inflated so much that he didn’t fit. He managed by opening a valve in his suit to let some pressure bleed off – a risky procedure. This information was withheld by the Russians, but the Judica-Cordiglias passed it on to NASA, believing it might save an astronaut’s life. A few weeks later, on 7 April 1965 General Nikolai Kamanin, Russia’s head of cosmonaut training, claimed that it was impossible that the brothers could have tracked any of their rockets. In an article published in The Daily Red Star, he called them “The Gangsters of Space!” According to Achille: “This denial only supported all the work we had done. We had succeeded with little equipment in undermining the Soviet Union.” By 20 July 1969, 12 extraordinary years had passed since Sputnik’s first beep. During that final emotional night at Torre Bert, it was all systems go as the Judica-Cordiglias reported the Moon landing live to millions of radio listeners. But it was the end of an era. The pictures were broadcast live on television. The mystery had gone; it was the beginning of the end for radio. It wasn’t the end of the brothers, though. They went on to set up Europe’s first cable TV network. Achille trained to become a ‘space doctor’ and is now a leading cardiologist, while Gian helps police to tap the mobile phones of Italy’s criminals. The Judica-Cordiglia brothers remain adamant that they recorded lost cosmonauts. Standing in front of their unique library of recordings, Gian told me: “Fifty years ago, it wasn’t possible to build a simple computer that weighed less than a ton, yet we were firing men and women into outer space who were prepared to die the loneliest of deaths. They were true heroes. And, thanks to radio, we know about their sacrifices.” He patted a shelf full of recordings. “We must never forget them.”

Credit: Alex Tomlinson ..

Credit: Alex Tomlinson FURTHER READING

Credit: Alex Tomlinson FILM INFO

Image courtesy of NASA. Credit: Alex Tomlinson HOW DID THE BROTHERS KNOW THEY

WERE TRACKING A SATELLITE?

Image courtesy of Judica-Cordiglia brothers. Credit: Alex Tomlinson HOW DID THEY KNOW WHEN TO LISTEN? The Judica-Cordiglias weren’t able to listen to the satellite transmissions all of the time because the orbit would take the satellite out of range to the other side of the planet. They had about 20 minutes during each orbit, so it was crucial that they knew when they could listen (they weren’t able to man their posts full-time). There was also the problem that the Earth’s rotation would mean the direction that their antennæ needed to be pointed in to get the best signal had to be changed to account for this. Their solution was simple. The Earth is inclined on

its own axis at an angle of 23.5 degrees. The brothers got a globe, straightened

it up and marked the satellite’s orbital path around it. A 360-degree rotation

of the Earth happens every 24 hours and so, by dividing 360 by 24 they

had the rotation of the Earth in one hour, namely 15 degrees. By measuring

the Doppler effect, it was possible to conclude that most satellites had

a rotational period of about 90 minutes around the Earth so that would

make 15 degrees plus 7.5 degrees, meaning the Earth will have shifted beneath

the satellite by 22.5 degrees, so they had the direction.

Image courtesy of Judica-Cordiglia brothers. Credit: Alex Tomlinson A LIST OF THE SUSPECTED LOST COSMONAUTS THE BROTHERS CLAIM TO HAVE RECORDED

Fortean Times: Lost in Space http://www.forteantimes.com/features/articles/1302/lost_in_space.html |

||||||||||||||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | ||||||||||||||

|

|