|

|

|||||||

|

1940's Russian Experiment ..

Related Links:

|

|||||||

|

.. .. 1940's Russian Experiment. Part 2 .. |

|||||||

| Science: Red

Research

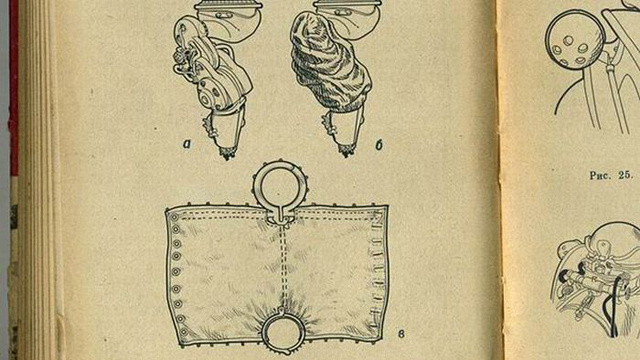

Monday, Nov. 22, 1943 Time Online A thousand U.S. scientists in Manhattan last week saw dead animals brought back to life. It was the first public U.S. showing of a film picturing an experiment by Soviet biologists. They drained the blood from a dog. Fifteen minutes after its heart had stopped beating, they pumped the blood back into its lifeless body with a machine called an autojector, serving as artificial heart and lungs. Soon the dog stirred, began to breathe; its heart began to beat. In twelve hours it was on its feet, wagging its tail, barking, fully recovered. This picture was shown to a Congress of American-Soviet Friendship. The film explained the work of a group of Russian scientists under Dr. Serge Bryukhonenko at the U.S.S.R. Institute of Experimental Physiology and Therapy at Moscow. The scientific audience thought this work might move many supposed biological impossibilities into the realm of the possible. The autojector, a relatively simple machine, has a vessel (the "lung") in which blood is supplied with oxygen, a pump that circulates the oxygenated blood through the arteries, another pump that takes blood from the veins back to the "lung" for more oxygen. Two other dogs on whom the experiment was performed in 1939 are still alive and healthy. The autojector can also keep a dog's heart beating outside its body, has kept a decapitated dog's head alive for hours—the head cocked its ears at a noise and licked its chops when citric acid was smeared on them. But the machine is incapable of reviving a whole dog more than about 15 minutes after its blood is drained—body cells then begin to disintegrate. Laboratory Faith. Eminent U.S. scientists who have visited Russia gave last week's Congress a well-documented report on Soviet scientific progress. In Russia schoolchildren are constantly confronted with posters proclaiming that science will solve the world's ills. Popular science magazines are widely read. Red science is a vast, centrally directed enterprise, with the U.S.S.R. Academy of Sciences at the top and hundreds of institutes working on assigned problems. No scientific frontier is neglected. Red scientists are well paid, get special vacation privileges, are rewarded with prizes up to 200,000 rubles for outstanding work, rank with writers in prestige. Practical Works. Among the great recent works of Soviet science are the explorations of some 1,200 geologists. Yale's Geologist Carl O. Dunbar reported that they have uncovered vast stores of metals, minerals and oil, keeping the Soviet war machine well supplied despite the temporary loss of resources to the Nazi invader. Since 1939 they have tripled known coal reserves. In chemistry the Russians have pioneered in the preparation and use of blood plasma, in synthetic rubber, photochemistry, explosives, helium, winter lubricants for tanks and planes. Dr. Wendell M. Stanley, famed virus investigator of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, told of a new Russian antiserum that has given the best results yet in preventing influenza. Soviet scientists have found ways to extract iodine cheaply from the foul waters of oilfields, sugar from watermelons, vitamin C from pine-tree needles for hungry Leningrad. Important contributions have been made to molecular physics, optics, electronics. Outstanding, however, and ranking with that of the U.S., is the Soviet work in botany and agriculture. Among many new crops are green, red and black cotton. The Russians have found a method of planting winter wheat (in unplowed stubble) that enables it to withstand Siberian temperatures of 40 below zero. By crossing Merino ewes with wild mountain rams, they have bred a hybrid mountain sheep that bears fine fleece wool. Through their pioneering Institute of Artificial Insemination, Russian biologists have produced 50,000,000 farm animals from vacuum-bottle spermatozoa. Because U.S. and U.S.S.R. soils, climate, crops, livestock and even landscapes are much alike, scientists of both countries have been eager to exchange information. Last week at the Congress, Dr. Charles E. Kellogg, U.S. Soil Survey chief, declared: "The Russian and American peoples have a splendid record of mutual aid . . . since the American Revolution. . . . The future promises even more." SOURCE: Time Online |

|||||||

| Science:

Transplanted Head

Monday, Jan. 17, 1955 Time Online In the Soviet Ogonek, Georgi Blok describes a sensational exhibit at a recent meeting of the Moscow Surgical Society. On the platform close to the guests of honor stood a large white dog, wagging its tail. From one side of its neck protruded the head of a small brown puppy. As the surgeons watched, the puppy's head bit the nearest white ear. The white head snarled. The two-headed dog, no freak of nature, was the latest product of Surgeon Vladimir Petrovich Demikhov, chief of the organ-transplanting laboratory of the Soviet Academy of Medical Sciences. Dr. Demikhov, says Blok, started in a small way by replacing the hearts of dogs with artificial blood pumps. Next, he planted a second heart in a dog's chest, removing part of a lung to make room for it. The extra heart continued its own rhythm, beating independently of the original heart. After repeating this operation many times, Dr. Demikhov could keep two-hearted dogs alive for as long as 2½ months. Sometimes the original heart stopped beating first. Then the second heart carried the burden until it failed too. Encouraged by his successes, Dr. Demikhov tried the reverse operation. He removed most of the body of a small puppy and grafted the head and forelegs to the neck of an adult dog. The big dog's heart, as Blok tells the story, pumped blood enough for both heads. When the multiple dog regained consciousness after the operation, the puppy's head woke up and yawned. The big head gave it a puzzled look and tried at first to shake it off. The puppy's head kept its own personality. Though handicapped by having almost no body of its own, it was as playful as any other puppy. It growled and snarled with mock fierceness or licked the hand that caressed it. The host-dog was bored by all this, but soon became reconciled to the unaccountable puppy that had sprouted out of its neck. When it got thirsty, the puppy got thirsty and lapped milk eagerly. When the laboratory grew hot, both host-dog and puppy put out their tongues and panted to cool off. After six days of life together, both heads and the common body died. Dr. Demikhov's two-headed dog, Blok points out, was not a mere stunt. It was part of a long-range attempt to learn how damaged organs can be replaced, or how their functions can be performed by mechanical substitutes. SOURCE: Time Online |

|||||||

Demikhov’s

Two-Headed Dogs

In 1954 Vladimir Demikhov shocked the world by unveiling a surgically created monstrosity: A two-headed dog. He created the creature in a lab on the outskirts of Moscow by grafting the head, shoulders, and front legs of a puppy onto the neck of a mature German shepherd. Demikhov paraded the dog before reporters from around the world. Journalists gasped as both heads simultaneously lapped at bowls of milk, and then cringed as the milk from the puppy's head dribbled out the unconnected stump of its esophageal tube. The Soviet Union proudly boasted that the dog was proof of their nation's medical preeminence. Over the course of the next fifteen years, Demikhov created a total of twenty of his two-headed dogs. None of them lived very long, as they inevitably succumbed to problems of tissue rejection. The record was a month. Demikhov explained that the dogs were part of a continuing series of experiments in surgical techniques, with his ultimate goal being to learn how to perform a human heart and lung transplant. Another surgeon beat him to this goal — Dr. Christian Baarnard in 1967 — but Demikhov is widely credited with paving the way for it. SOURCE: Museum of Hoaxes |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |||||||

|

|