|

|

Charles

V, the son of Philip of Burgundy and Joanna the Mad, was to be the most

powerful Habsburg of all. He funded Magellan’s voyage around the world

in the Spanish ship Victoria. When Philip died in 1506, Charles inherited

Burgundy and the Netherlands. In 1516 Ferdinand of Spain left him Spain

and Naples, and in 1519 he inherited the Holy Roman Empire from Maximilian.

This led to rivalry with Francis I of France, who also wanted to be Holy

Roman emperor, and their countries were at war for most of Charles’s reign. Charles

V, the son of Philip of Burgundy and Joanna the Mad, was to be the most

powerful Habsburg of all. He funded Magellan’s voyage around the world

in the Spanish ship Victoria. When Philip died in 1506, Charles inherited

Burgundy and the Netherlands. In 1516 Ferdinand of Spain left him Spain

and Naples, and in 1519 he inherited the Holy Roman Empire from Maximilian.

This led to rivalry with Francis I of France, who also wanted to be Holy

Roman emperor, and their countries were at war for most of Charles’s reign.In 1522 Emperor Charles V drove the French out of Milan. In 1529, in the Peace of Cambrai between France and Spain, France renounced claims to Italy. The Treaty of Barcelona was signed by Charles V and Pope Clement VII. In 1530 he gave the island of Malta to the Knights of St John. In 1544, Charles V and Henry VIII invaded France. A devout Catholic, Charles also had to deal with problems

in the Holy Roman Empire caused by people in Germany who had become Protestants

after the Reformation. In 1546 Charles took up arms against some of them who

had formed the League of Schmalkalden. He defeated them in 1547, but four

years later he was forced to agree to their demands. By 1556, Charles was

exhausted by all these wars. He retired to a monastery, having divided

his lands between his son, Philip (who ruled Spain and the Netherlands)

and his brother, Ferdinand (who ruled Germany and Austria).  An elderly Karl V (also known as Don Carlos I of Spain), ruler of the Holy Roman Empire Alternative Title: Charles I of Spain |

Desiderius

Erasmus (c. 1466-1536) was a Dutch priest and Renaissance scholar who encouraged

a form of Humanism which laid stress on free will and taught that people

should think for themselves in spiritual matters. He was, however, repelled

by the violence that accompanied the Reformation when it came. Desiderius

Erasmus (c. 1466-1536) was a Dutch priest and Renaissance scholar who encouraged

a form of Humanism which laid stress on free will and taught that people

should think for themselves in spiritual matters. He was, however, repelled

by the violence that accompanied the Reformation when it came. He published an edition of the Greek New Testament. Though a Catholic, he clashed with the Church when he urged reforms to make the Church less worldly. In 1559 his books were placed on the Index of forbidden books. Erasmus Text

Project: The University of the South - [inactive link]

Desiderius

Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466/69–1536) was a renowned humanist scholar and

theologian. He moved in 1521 to Basel, the city where Hans Holbein the

Younger lived and had his workshop. Such was the fame of Erasmus, who

corresponded with scholars throughout Europe, that he needed many

portraits of himself to send abroad. Holbein painted three much-copied

portraits of Erasmus in 1523, of which this is the largest and most

elaborate. It is likely the one sent to William Warham, Archbishop of

Canterbury, in England. Holbein later painted Warham after he travelled

to England in 1526 in search of work, with a recommendation from

Erasmus, who had once lived in England himself. Holbein's portrait of

Erasmus includes a Latin couplet by the scholar, inscribed on the edge

of the leaning book on the shelf, which states that Holbein would rather

have a slanderer than an imitator. According to art historian Stephanie

Buck, this portrait is "an idealized picture of a sensitive, highly

cultivated scholar, and this was precisely how Erasmus wanted to be

remembered by future generations" (Stephanie Buck, Hans Holbein,

Cologne: Könemann, 1999, ISBN 3829025831, p. 50). ~ Painting by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543) - Web Gallery of Art

|

Ferdinand

was the joint ruler, with his wife Isabella, of the Spanish kingdoms of

Castile and Aragon from 1474 until Isabella’s death in 1504. Ferdinand

continued to rule alone until his death in 1516. Together they united Spain

and laid the foundations of its imperial greatness. Ferdinand

was the joint ruler, with his wife Isabella, of the Spanish kingdoms of

Castile and Aragon from 1474 until Isabella’s death in 1504. Ferdinand

continued to rule alone until his death in 1516. Together they united Spain

and laid the foundations of its imperial greatness.In the 15th century, Spain was divided into four different kingdoms. The two biggest were Castile and Aragon. The first step towards uniting Spain was made in 1469 when Ferdinand and Isabella married. They succeeded the king of Castile when he died. In 1479 Ferdinand inherited Aragon and later made Isabella joint ruler of Aragon as well. In 1492-1512 he conquered Granada, Naples and Navarre. With the two kingdoms united, Spain grew more powerful. Both Ferdinand and Isabella were devout Catholics and the Inquisition was established under their rule. It was a religious court that punished people who did not accept the Catholic Church’s teachings. It operated with great severity; people were tried in secret and tortured until they confessed. Those who did confess could be fined, while those who refused were either imprisoned or burned to death. At this time, there were many Jews living in Spain and the Inquisition was used against them. In 1492 as many as 200,000 of them were expelled from Spain. In the same year, the Moorish State of Granada was recaptured. Many of the Muslim Moors, who were expelled, went to live in North Africa. Isabella sponsored Christopher Columbus’s voyage, which ended in the Americas. In 1511 Ferdinand and Henry VIII of England joined

the Holy League against France. Ferdinand and Isabella had five children.

One was Catherine of Aragon who married Henry VIII of England. But they

had no son and so descent passed through their daughter Joanna the Mad.

Charles V, of the Habsburgs, who had already inherited Burgundy and the

Netherlands, also inherited Spain and Naples from Ferdinand.

|

Henry

VII (1457-1509) was the first Tudor king, who wrested the English throne

from Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. His claim rested

on his descent from John of Gaunt. Henry

VII (1457-1509) was the first Tudor king, who wrested the English throne

from Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. His claim rested

on his descent from John of Gaunt. The Wars of the Roses is the name given to the struggle between two branches of the Plantagenet family for the English throne. Called the House of York and the House of Lancaster, both were descended from Edward III. Trouble began in 1453 when King Henry VI, of the House of Lancaster, went mad. His distant cousin, Richard, Duke of York, became Lord Protector (regent) and ruled for him. When Henry suddenly recovered, war broke out between Richard of York and his supporters and the Lancastrian advisers to Henry VI. Although Richard was killed, the Yorkists triumphed and in 1461 Richard’s son became Edward IV. Henry VI was later murdered. When Edward died 12 years later, his young son Edward V succeeded him, under the care of his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester. After a few weeks Richard seized the throne, saying that Edward V was illegitimate. Edward and his younger brother were possibly murdered. The remaining Lancastrian heir, Henry Tudor, defeated and killed Richard, becoming King Henry VII. Henry ended the feud at the heart of the Wars of the Roses by marrying the Yorkist heiress Elizabeth. His sound administration helped to mend the damage done by 30 years of civil war and his reign is often seen as the start of modern history. Henry VII’s heraldic device was a sprig of hawthorn because Richard III’s crown was found under a hawthorn bush after the Battle of Bosworth Field. He also devised the ‘Tudor Rose’, with red and white petals symbolizing the union of the red rose of Lancaster and the white rose of York. In 1496 he joined the Holy league, made up of Milan, Venice, Maximilan I, Pope Alexander VI and Ferdinand of Spain. Henry died at Richmond in 1509.  Young Henry VII, by a French artist (Musée Calvet, Avignon) |

Henry

VIII (1491-1547) became King of England upon the death of his father Henry

VII in 1509. At this time, England was an important power in Europe. Henry

VIII (1491-1547) became King of England upon the death of his father Henry

VII in 1509. At this time, England was an important power in Europe.During his youth, Henry was an accomplished musician, sportsman and scholar - the perfect Renaissance prince. Under the influence of his ambitious chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, the first part of Henry’s reign saw war against France. He strengthened the English navy and his pride and joy was a ship called the Mary Rose. After it had been refitted in 1536, Henry and his court went to watch it sail on the Solent. Some 700 sailors, soldiers and archers stood on the deck. This affected the ship’s balance so much that, when a gust of wind blew, it quickly sank. In 1520 he met Francis I of France, in Flanders, at the ‘Field of the Cloth of Gold’ to make an alliance between their countries. Instead the event turned into a contest between the two kings with each trying to outdo the other in the splendour of his arrival. In 1521 he supported the pope against Martin Luther, and was made ‘Defender of the Faith’. As Henry wanted a son to make the Tudor dynasty secure, he decided to divorce Catherine of Aragon and marry again. When the pope refused to dissolve the marriage, he broke all links with Rome (with the help of Thomas Cromwell, his chief minister, and Thomas Cranmer, then Archbishop of Canterbury) and made himself head of the new Church of England in 1534, ushering in the English Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries (selling most of the monasteries’ land to help pay for the wars against France). This new Church granted him a divorce and he married Anne Boleyn in 1533. Henry executed his second wife; his third wife, Jane Seymour, died after giving birth to the future Edward VI. His fourth marriage, to Anne of Cleves, was a diplomatic union; Henry disliked her - calling her the ‘Flanders mare’ - and quickly divorced her in order to marry Catherine Howard (1540), executed two years later on a charge of adultery. In his final years Henry, now contentedly married to Catherine Parr, forming an alliance with Charles V. He renewed war with France and Scotland, and ruled as a tyrant at home. As a youth, Henry was well loved, earning the nickname

‘Bluff King Hal’. However, this affection turned to fear, as he became

obese and bad-tempered, suffering from painful leg ulcers.  Eighteen-year-old Henry VIII after his coronation in 1509 |

|

Isabella and Ferdinand are known

for completing the Reconquista, ordering conversion or exile of their

Muslim and Jewish subjects in the Spanish Inquisition, and for

supporting and financing Christopher Columbus' 1492 voyage that led to

the opening of the New World and to the establishment of Spain as the

first global power which dominated Europe and much of the world for more

than a century. Isabella was granted the title Servant of God by the

Catholic Church in 1974.

|

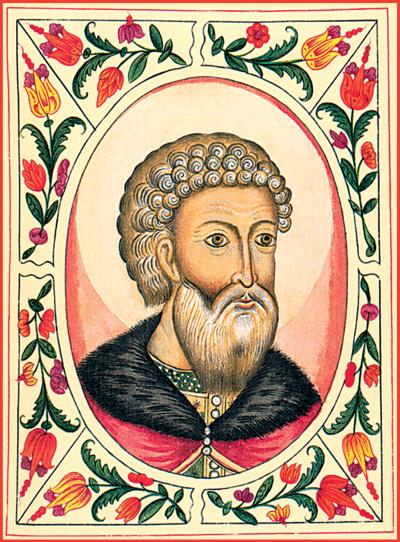

In 1462 Ivan III, also known as Ivan the Great, became

duke of Muscovy (until 1505). In 1462 Ivan III, also known as Ivan the Great, became

duke of Muscovy (until 1505). In 1472 he married ZoÎ Palaeologus, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor. He adopted the Byzantine emblem of a double-headed eagle as his own, appointing himself protector of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In 1478 Ivan conquered Novgorod and made it part of the duchy of Moscow. Until the middle of the 15th century, much of southern Russia was under the control of the Mongol rulers of the Golden Horde, who were also known as Tartars. Ivan, however, succeeded in making his lands independent of the khanate of the Golden Horde. By 1480 Ivan was able to call himself the “Tsar of all the Russias” (“tsar” from the Latin “Caesar”). He made Moscow his capital and brought Italian architects to rebuild its kremlin (citadel) which had been damaged by fire. The Cathedral of the Assumption (1475-9) and especially that of Archangel Michael (1505-08), with its traditional medieval onion-shaped domes surmounting Renaissance facades, show the composite style at its best. The octagonal Ivan the Great bell tower houses 21 bells, the largest of which weighs 64 tons. In 1497 Ivan introduced a new legal code. By 1500 Russia had become one of the great powers of Europe. Ivan died an alcoholic in 1505. Ivan III of Russia The Russian Coat of Arms The Two-headed Eagle serves as the Russian Coat

of Arms since 15th century, when it was borrowed by Tsar Ivan the III from

Bysanthy. The original color was black, as one can still see it on the

Albanian State Flag. With the expansion of the Russian Empire the Eagle

was decorated with shields of conquered countries and regions. After the

Socialist Revolution in 1917 such a coat was abandoned. Since 1991, when

Russia restored its independence, a number of attempts to adopt the official

coat of arms were undertaken. In 1994 Russian Duma approved the coat featuring

the Two-headed Eagle as the official one. The shield of St.George The Victor

serves as the Moscow city shield since 15th century even without interruption

and is added to the coat of arms as a symbol of the capital.

|

|

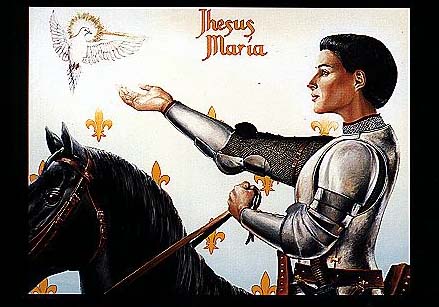

Joan of Arc (c.1412-31) is a French national heroine,

nicknamed the ‘Maid of Orleans’, who inspired her fellow countrymen’s victory

over England in the Hundred Years’ War.

She was the daughter of a farmer. When she was about 16, she claimed that Saints Michael, Catherine and Margaret had told her in a vision to lead the French against the English. She persuaded the heir to the French throne, the Dauphin Charles, to let her command a force. She relieved the besieged city of Orleans in 1429, enabling the French dauphin to be crowned as Charles VII. That year she defeated another English force at Patay. In 1430 she tried to regain Paris, but was captured by a Burgundian army and sold to the English regent, the Duke of Bedford who put her on trial for heresy and sorcery. She was found guilty and burned at the stake. Joan of Arc was made a saint of the Roman Catholic Church in 1920. Her story has inspired many books, films and plays, most notably George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan.   Joan of arc miniature graded. Derived from original commons upload at which is now in the history version: 01:39, 13. 8. 2005 Colour-graded to reveal more detail |

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was an Italian artist

and possibly the most versatile genius who ever lived. The illegitimate

son of a Florentine lawyer, Leonardo was the embodiment of what came to

be called Renaissance man - one skilled in a wide range of activities.

His fields of research included anatomy, botany, hydraulics, engineering,

mathematics and philosophy, as well as sculpture and painting. Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) was an Italian artist

and possibly the most versatile genius who ever lived. The illegitimate

son of a Florentine lawyer, Leonardo was the embodiment of what came to

be called Renaissance man - one skilled in a wide range of activities.

His fields of research included anatomy, botany, hydraulics, engineering,

mathematics and philosophy, as well as sculpture and painting. Very few of Leonardo’s paintings, however, were completed. He left The Adoration of the Magi (1481) unfinished in Florence and went to Milan, where he produced his most famous early work, the Last Supper (c. 1497). In c.1503 he painted the enigmatic Mona Lisa - the world’s most famous portrait. Supposedly of a Florentine official’s wife, the portrait was painted between about 1503 and 1507, and is sometimes thought to be a self-portrait. The painting was one of the few works that Leonardo completed. It broke new ground by portraying the subject’s features with more naturalism and subtlety than had previously been achieved. Leonardo experimented with different techniques and

mediums and perfected a subtle method for differentiating light and shade His notebooks contain sketches of flowers and animals, studies of human anatomy, and architectural and technical drawings, including a design for a helicopter. Leonardo understood the principles of flight 400 years before the first planes. He called it an ‘air gyroscope’; his design, if built, would have risen into the air and then dropped. He designed machines called ornithopters, which he thought would carry people through the air if they flapped the wings as birds do. In another sketch of a flying machine, a man flaps four wings with a system of pulleys and treadles. Leonardo also designed a sophisticated water turbine engine. He designed locks for the Languedoc Canal in France, which was completed in 1681. He was a pioneer of anatomy, and produced amazing drawings, such as a fetus in its mother’s womb. His influence on the development of art, and on other

artists of his age such as Michelangelo and Raphael, was immense. Image: Francesco Melzi - Portrait of Leonardo - WGA14795

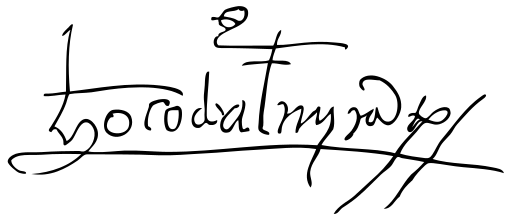

Leonardo's Signature, by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) Page (Recto 89) from volume III of The Forster Codex. Italy, 15th-16th century |

In 1469 Lorenzo de Medici (1449-92) became unofficial

ruler of Florence, with his brother Giuliano. The Medici family was the

greatest financiers in Europe. They were educated in the classics and supported

new artists and their ideas. Michelangelo’s first commissions came from

Lorenzo de Medici, and it was Medici money that attracted Leonardo da Vinci

to the city. Although books were very expensive, Lorenzo was able to collect

together a great private library in Florence. In 1571 it was re-founded

as a public library in a building designed by Michelangelo. In 1469 Lorenzo de Medici (1449-92) became unofficial

ruler of Florence, with his brother Giuliano. The Medici family was the

greatest financiers in Europe. They were educated in the classics and supported

new artists and their ideas. Michelangelo’s first commissions came from

Lorenzo de Medici, and it was Medici money that attracted Leonardo da Vinci

to the city. Although books were very expensive, Lorenzo was able to collect

together a great private library in Florence. In 1571 it was re-founded

as a public library in a building designed by Michelangelo. At this time Italy was divided into small states. Many

of them were large cities, such as Florence, Venice and Rome. Others were

ducal courts such as Mantua, Urbino and Ferrara. Most of these states were

ruled by families who had grown rich on trade and commerce in the late

Middle Ages. Under Lorenzo’s influence, Florence became one of the most

beautiful and prosperous cities in Italy, as well as a centre of the Renaissance.

Lorenzo had a large art collection of his own and, through his writings,

helped to make the form of Italian spoken in Florence into the language

of the whole country. Florentine Italian is still the standard today. |

|

BORN: 29 NOVEMBER 1489 DIED: 18 OCTOBER 1541 Margaret Tudor was the first daughter born to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. She was married to James IV of Scotland on 8 August, 1503 at Holyrood House. Margaret was apparently not happy in her early days in Scotland, as is evident in a letter she wrote to her father, Henry VII. The two different handwritings in the letter are because the top part was written by a secretary, while the last section was in Margaret's own hand. James died at Flodden Field 9 September 1513. When James IV died, Margaret's infant son became James V. It was because of this union that England and Scotland would be united under one crown 100 years later at the death of Elizabeth I in 1603. John Stuart, Duke of Albany, used the Scottish Lord's distrust of Margaret to make himself regent and sent the Queen to flee to England in 1516 with her second husband, the Earl of Angus.

Richard Grafton describes Margaret's departure for Scotland for her wedding: "Thus this fair lady was conveyed with a great company of lords, ladies, knights, esquires and gentlemen until she came to Berwick and from there to a village called Lambton Kirk in Scotland where the king with the flower of Scotland was ready to receive her, to whom the earl of Northumberland according to his commission delivered her."And later he says: "Then this lady was taken to the town of Edinburgh, and there the day after King James IV in the presence of all his nobility married the said princess, and feasted the English lords, and showed them jousts and other pastimes, very honourably, after the fashion of this rude country. When all things were done and finished according to their commission the earl of Surrey with all the English lords and ladies returned to their country, giving more praise to the manhood than to the good manner and nature of Scotland."Polydore Virgil writes: "This year also Margaret, queen of Scots, wife of James IV killed at Flodden in the fifth year of the king's reign, and elder sister of the king, after the death of her husband married Archibald Douglas, earl of Angus, without the consent of the King her brother or the council of Scotland, with which he was not pleased. But after that there arose such strife between the lords of Scotland that she and her husband came into England like banished persons, and wrote to the king for mercy and comfort. The king, ever inclined to mercy, sent them clothing and vessels and all things necessary, wishing them to stay in Northumberland until they knew further of his wishes. And the queen was there delivered of a fair lady called Margaret, and all the country were commanded by the king to do them pleasure."  Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VII of England, sister of Henry VIII, wife of James IV of Scotland and mother of James V. |

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a German priest whose

criticism of the Roman Catholic Church initiated the Reformation, which

led to the rise of Protestantism Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a German priest whose

criticism of the Roman Catholic Church initiated the Reformation, which

led to the rise of Protestantism

As professor of Biblical Exegesis at the University of Wittenburg he compiled a list of Ninety-Five Theses that attacked the Church for selling indulgences (promises of God’s forgiveness in return for money), and argued that faith alone is sufficient for salvation. He denied the authority of the pope and other aspects of Catholic doctrine, including transubstantiation, and wrote many books and pamphlets. In 1517 Luther nailed his Ninety-Five Theses to a church door, and thus the revolution began. Widespread discontent with the state of the church was set alight by Luther’s criticisms. In 1521 the Diet of Worms took place. It was a meeting called by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V at Worms, Germany, to interrogate Luther and encourage him to withdraw his views. Luther, who had already been excommunicated by the pope, refused to retract, saying: "Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me." The Diet banned his works. The Reformation was the key event of the century. From Germany it spread throughout northern Europe. New Protestant churches sprang up, inspired not only by Luther, but by the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli, French theologian John Calvin, and others. They aimed to follow only the teachings of the Bible, getting rid of church traditions. Several powerful kings and princes supported them. Zwingli’s views were more extreme than Luther’s. In 1524 he banned Catholic mass in Zurich. This led to a civil war in which Zwingli was killed. Zwingli was followed by Calvin, who completed the Reformation in Switzerland and influenced John Knox who took the Reformation to Scotland. Both Catholics and Protestants used illustrated pamphlets and books to promote their views. New techniques of printing spread their ideas. The reformers, who wanted the Bible to be available to everyone, produced new translations of it and boosted overall literacy. (In 1526, William Tyndale, the English theologian, translated the New Testament into English.) Luther’s German Bible and, later, the Authorized Version in England were so influential that they helped to shape the development of the German and English languages. Although the Catholic church responded by introducing reforms from within, beginning with the Roman Catholic Council of Trent (1545-63) which met to organize the program of reform, violent conflict between Catholics and the reformers (called Protestants) followed. The Catholic reform movement was called the Counter-Reformation. Christians in Europe split into violent rival groups. War often broke out as each country struggled with the new religious alliances. Spanish nobleman Ignatius de Loyola founded the Society

of Jesus, or the Jesuits, as the missionaries of the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

From 1550, Jesuits were in action all over Europe, and soon they began

converting the peoples of the Americas to Christianity. Wherever

traders went, Jesuits followed. In England, Henry VIII took the helm of the English church because the Pope would not let him divorce his first wife. He dissolved the monasteries and took over their property, but allowed church services to continue in their old form. During the reign of his son Edward VI (1537-53), a Protestant government brought the Reformation to England. Church services were changed and church decoration was simplified. After Edward’s death his half-sister Mary, a devout Catholic, tried to restore her church’s authority in England, executing many Protestants in the process. After “Bloody” Mary’s death in 1558, Elizabeth I backed a moderate form of Protestantism against both Catholics and radical Protestants, such as the Puritans, for whom the Church of England was not reformed enough. Philip II of Spain was the most powerful Catholic monarch

in Europe. When Queen Elizabeth I executed Mary Queen of Scots, he organized

a fleet (the Spanish Armada) to invade England and restore Catholic rule.

It set sail in July 1588. The Spanish had 130 ships; the English had less

than 100. In August 1588 the English fleet defeated Philip’s massive invasion

fleet. The victory was a triumph for Protestantism. In 1605, a Catholic plot to murder James I of England

was discovered. Guy Fawkes was planning to light gunpowder in the cellars

of Parliament while James was giving an address; he was caught and executed

after torture. The discovery of the Gunpowder Plot led to greater persecution

of English Catholics. The Lutheran Church today is a Protestant denomination with a large following in Germany and Scandinavia. It accepts Luther’s teachings and stresses the importance of ‘justification’ (being made righteous) by God’s grace, which is received through faith alone. The Church is non-hierarchical and grants autonomy to each individual congregation. Lutherans are known for their choral and organ music.

J. S. Bach wrote much of his music for Lutheran worship. |

|

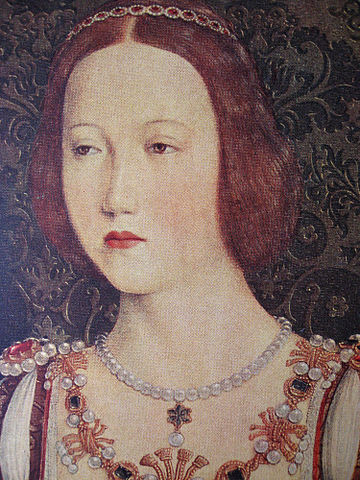

QUEEN OF FRANCE AND DUCHESS OF SUFFOLK La volenté de Dieu me suffit (The will of God is sufficient for me) BORN: 18 MARCH 1496  Princess

Mary Rose Tudor was born to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York on March 18,

1496 [1] and was the youngest child of the King and Queen to live past

childhood. As she grew, Mary became a beautiful lady and was considered

to be one of the most attractive women in Europe at the time. Princess

Mary Rose Tudor was born to Henry VII and Elizabeth of York on March 18,

1496 [1] and was the youngest child of the King and Queen to live past

childhood. As she grew, Mary became a beautiful lady and was considered

to be one of the most attractive women in Europe at the time.

Mary was betrothed to Charles (the future Holy Roman Emperor), who, through his mother, was a nephew of Catherine of Aragon, with a marriage planned for May 1514. After diplomatic delays and secret dealings between Spain, the Holy Roman Empire and France, Henry VIII (Mary's brother) canceled the betrothal. Mary was apparently please with this, since she probably had no desire to marry a boy four years younger. Unfortunately, Henry's choice for a replacement was 34 years older than she- Louis XII, King of France, described as "feeble and pocky" and not a very pleasing prospect for a young, healthy and beautiful Princess. The King was a widower with no heir, and Henry was more than ready to supply his sister as a way of making truce with a continental power. Of course, Mary had no say in all these matter, since royal princesses were commonly regarded as a bartered commodity. Mary must have known this was her fate, but she still had to have been by it, since she had fallen in love with her brother's friend, Charles Brandon. Brandon was the Duke of Suffolk, but was not royal; the title was granted because of his father's loyalty and service at Bosworth field. But Mary wanted to wed him, even though such a match would have been considered her marrying beneath her. In turn, Charles was attracted to the princess, and was available, with two annulled marriages and a broken precontract. Mary refused to wed the French king, weeping and sulking, and demanding to be allowed to marry Charles. Of course, her brother refused. So, Mary struck a deal with Henry: she would do her princess duty and marry the French King. But, if she were to outlive Louis, which was very likely, she wanted her next husband to be one of her own choosing. Henry agreed, quite possibly with the intention of never honoring his promise. Mary first took part in a proxy marriage, with the Duc de Longueville standing in for Louis. A month later, Mary traveled to Paris for her real marriage to the 52 year old King of France. Most of the English entourage the princess had brought with her to France were sent back, although a few, including the Boleyn sisters Anne and Mary, remained. Mary remained the complacent princess, biding her time. The two were married in the fall of 1514, followed by weeks of celebrations, which obviously put a strain on her aging new husband. Louis XII died New Year's Day 1515, after just three months of marriage. Mary, now Queen Dowager, moved to the Palais de Cluny where she was isolated from all men (except the new King, Francis, and her confessor) for six weeks to see if she was pregnant by the late king, and if so, to ensure it was his child.

Mary sought an ally in Francis, the new king. When Brandon arrived in Paris, Francis confronted him about his feelings for Mary. He admitted that he wanted to marry her. Charles then met with Mary herself, where she told him about her plan. She wanted to marry him, but if he didn't feel the same, she would enter a convent and no longer be a marriage pawn for Henry VIII. Charles gave in, even though he knew that his King would be very upset at the turn of events. In the small chapel of the Palais de Cluny, Mary Tudor did the unimaginable for a princess, she married the man *she* chose. When Henry found out about the marriage, he was furious. However, Mary was his favorite sister and Charles was an old friend, and the couple was soon forgiven. Mary and Charles named their first child Henry (1515-1534), in honor of her brother. Their second child was given the female version of the name of one who helped bring their marriage about -- the girl was named Frances (1517-1559). Their third child was a daughter named Eleanor (1519-1547). Mary was always referred to as the Queen of France (commonly "The French Queen") and never as the Duchess of Suffolk. This was probably to remind her that she had married below her rank. But Mary essentially lived a quiet and happy remainder of her life. Mary was good friends with her sister-in-law Catherine

of Aragon, and was a supporter of hers in the 'great matter' of the divorce

and rejected Anne Boleyn. Mary's health began to fail in 1533, and she

died on June 24 of that year. Mary was interred at St. Mary's Church in

Bury St. Edmunds in Suffolk.  Mary Tudor and Charles Brandon |

Clement VII was elected as pope in 1523. Clement VII was elected as pope in 1523.

In 1525, at the battle of Pavia, Francis I of France was captured by the Spaniards. He was released a year later in return for giving up his claim to Milan, Genoa and Naples. He failed to keep this promise and instead forms an alliance with Pope Clement VII, Milan, Venice and Florence against Charles V. In 1529, in the Peace of Cambrai between France and

Spain, France renounces claims to Italy. The Treaty of Barcelona was signed

by Pope Clement VII and Charles V. Pope Clement VII (Italian: Papa

Clemente VII; Latin: Clemens VII) (26 May 1478 – 25 September 1534),

born Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici, was Pope from 19 November 1523 to

his death in 1534. The Sack of Rome and English Reformation occurred during his papacy. Giulio de' Medici was born in

Florence one month after the assassination of his father, Giuliano de'

Medici, following the Pazzi Conspiracy. Although his parents had not had

a formal marriage, they had been formally betrothed per sponsalia de

presenti , and therefore canon law recognized that Giulio was born

legitimate. Despite this accommodation for an important and powerful

family, Giulio was considered illegitimate by his contemporaries. He was

the nephew of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who educated him in his youth.

Giulio's mother, Fioretta Gorini, also died leaving him an orphan. |

Richard III was born in 1452. He was the brother of

Edward IV. Richard III was born in 1452. He was the brother of

Edward IV.

In 1471 Henry VI was murdered. Richard may have been present at the murder. In 1483 Richard became Lord Protector for his nephew, Edward V, and took the throne. Edward V and his younger brother Richard were imprisoned

in the Tower of London, where they died, possibly murdered. Because of

this Richard gained a reputation as a cruel tyrant, a reputation which

he may not have deserved. He gave generously to schools, colleges and the

Church. Although he is often portrayed as a hunchback, there is no contemporary

evidence for this. If he did have a deformity, it was not very noticeable. In 1485 he died at the battle of Bosworth Field. In around 1591, William Shakespeare wrote a historical

drama about Richard III. The play portrays the ruthless pursuit of the

crown by the hunchback Richard of Gloucester. When the king, Edward IV,

is close to death, Richard starts to claw his way to the throne by having

his brother murdered and then cynically marrying the Prince of Wales’s

widow Anne. When Edward dies, Richard eliminates his opponents one by one,

is proclaimed king and decrees the death of his young nephews, the Princes

in the Tower. Eventually, however, his enemies - led by Henry Tudor

- defeat him at Bosworth. Some of the best-known lines from Richard III

are: ‘My horse, my horse, my kingdom for a horse!’ and ‘Now is the winter

of our discontent/Made glorious summer by this sun of York.’ Richard III

completed the series of plays begun with the Henry VI dramas, giving a

vivid account of 63 turbulent years of English history. The actor Antony Sher created a menacing Richard III in the Royal Shakespeare Company’s 1984-5 production of the play. Sher exaggerated Richard’s hunched back to symbolize his moral deformity, and played him as a cripple, dragging himself about on crutches. The costume enhanced the spidery silhouette. The Richard III Society was set up in 1924 to try to

restore the king’s reputation, which the members maintain Shakespeare had

distorted and unfairly destroyed. |

The Renaissance was a time of great prosperity in Italy,

but some Christians condemned the luxury and vanity of the rich. One such

was Girolamo Savonarola (1452-98), who ruled Florence from 1494 to 1498.

He inspired the people of Florence to depose the Medici family. Under his

influence, the rulers of Florence instituted a stern puritanical regime.

He had great bonfires (the 'bonfire of the vanities') built on which people

burnt their precious possessions. Personal ornaments, gambling equipment

and pictures went up in smoke. The Renaissance was a time of great prosperity in Italy,

but some Christians condemned the luxury and vanity of the rich. One such

was Girolamo Savonarola (1452-98), who ruled Florence from 1494 to 1498.

He inspired the people of Florence to depose the Medici family. Under his

influence, the rulers of Florence instituted a stern puritanical regime.

He had great bonfires (the 'bonfire of the vanities') built on which people

burnt their precious possessions. Personal ornaments, gambling equipment

and pictures went up in smoke.

Savonarola's political enemies, including the Medici

family, conspired with the Pope, whom he had insulted, to secure his excommunication.

He was convicted of heresy and duly executed. Girolamo Savonarola (21 September

1452 – 23 May 1498) was an Italian Dominican friar and preacher active

in Renaissance Florence. He was known for his prophecies of civic glory,

the destruction of secular art and culture, and his calls for Christian

renewal. He denounced clerical corruption, despotic rule and the

exploitation of the poor. He prophesied the coming of a biblical flood

and a new Cyrus from the north who would reform the Church. In September

1494, when Charles VIII of France invaded Italy and threatened

Florence, such prophesies seemed on the verge of fulfillment. While

Savonarola intervened with the French king, the Florentines expelled the

ruling Medici and, at the friar's urging, established a "popular"

republic. Declaring that Florence would be the New Jerusalem, the world

center of Christianity and "richer, more powerful, more glorious than

ever", he instituted a campaign of extreme austerity, enlisting the

active help of Florentine youth.  Girolamo Savonarola Fra Bartolomeo - Florence, Museo di San Marco |

In the 15th century Europeans began to look for sea

routes to Asia, hoping to obtain its goods more cheaply than by the ancient

land routes. The Portuguese led the way. After winning their independence

from Spain in 1385, they began to expand, attacking Muslim North Africa

and Muslim fleets at sea. King Joao I appointed his son, Prince Henry,

to organize voyages of discovery. In 1444 Henry’s sailors reached the Senegal

River in West Africa. By 1471, they had reached Ghana. In 1482-84 Diego

Ceo’s expedition came to the Congo river in Zaire. Bartholomeu Diaz rounded

the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa in 1487-88. In the 15th century Europeans began to look for sea

routes to Asia, hoping to obtain its goods more cheaply than by the ancient

land routes. The Portuguese led the way. After winning their independence

from Spain in 1385, they began to expand, attacking Muslim North Africa

and Muslim fleets at sea. King Joao I appointed his son, Prince Henry,

to organize voyages of discovery. In 1444 Henry’s sailors reached the Senegal

River in West Africa. By 1471, they had reached Ghana. In 1482-84 Diego

Ceo’s expedition came to the Congo river in Zaire. Bartholomeu Diaz rounded

the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa in 1487-88.

Vasco da Gama (c.1460-1524) was a Portuguese explorer who in 1497-9 led the first expedition to sail from Europe to India via the Cape of Good Hope, on the southern tip of Africa. After that, he sailed up the East Coast of Africa and with the help of an Indian sailor crossed the ocean to Calicut in India. He returned home with a cargo of spices. He returned to India in 1502 and again in 1522. Most early Portuguese explorers sailed in caravels. They were longer and narrower than previous ships, easier to manoeuvre with a greater spread of sail, and better able to withstand storms. They had large holds capable of carrying the substantial cargoes needed for long voyages. Vasco da Gama’s small ships were a development of the caravel and its triangular, lateen sail. They had both square and lateen rigged sails, which made them a great deal more maneuverable on the open sea. Portuguese sailors also benefited from improved maps,

astrolabes, and navigational training, largely thanks to Prince Henry the

Navigator. Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of

Vidigueira (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈvaʃku ðɐ ˈɣɐmɐ]; c. 1460s – 24

December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to

reach India by sea. His initial voyage to India (1497–1499) was the

first to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route, connecting the Atlantic

and the Indian oceans and, in this way, the West and the Orient. Vasco da Gama's signature (reads Ho Comde Almirante, "The Admiral Count")  |

|

TO HENRY VII

|

|

RECORDED BY ROBERT WYNKFIELD  Her prayers being ended, the executioners, kneeling,

desired her Grace to forgive then her death: who answered, ‘I forgive you

with all my heart, for now, I hope, you shall make an end of all my troubles.’

Then they, with her two women, helping her up, began to disrobe her of

her apparel: then she, laying her crucifix upon the stool, one of the executioners

took from her neck the Agnus Dei, which she, laying hands off it, gave

to one of her women, and told the executioner, he should be answered money

for it. Then she suffered them, with her two women, to disrobe her of her

chain of pomander beads and all other apparel most willingly, and with

joy rather than sorrow, helped to make unready herself, putting on a pair

of sleeves with her own hands which they had pulled off, and that with

some haste, as if she had longed to be gone. Her prayers being ended, the executioners, kneeling,

desired her Grace to forgive then her death: who answered, ‘I forgive you

with all my heart, for now, I hope, you shall make an end of all my troubles.’

Then they, with her two women, helping her up, began to disrobe her of

her apparel: then she, laying her crucifix upon the stool, one of the executioners

took from her neck the Agnus Dei, which she, laying hands off it, gave

to one of her women, and told the executioner, he should be answered money

for it. Then she suffered them, with her two women, to disrobe her of her

chain of pomander beads and all other apparel most willingly, and with

joy rather than sorrow, helped to make unready herself, putting on a pair

of sleeves with her own hands which they had pulled off, and that with

some haste, as if she had longed to be gone.

All this time they were pulling off her apparel, she never changed her countenance, but with smiling cheer she uttered these words, "that she never had such grooms to make her unready, and that she never put off her clothes before such a company." Then she, being stripped of all her apparel saving her petticoat and kirtle, her two women beholding her made great lamentation, and crying and crossing themselves prayed in Latin. She, turning herself to them, embracing them, said these words in French, ‘Ne crie vous, j’ay prome pour vous’, and so crossing and kissing them, bad them pray for her and rejoice and not weep, for that now they should see an end of all their mistress’s troubles. Then she, with a smiling countenance, turning to her men servants, as Melvin and the rest, standing upon a bench nigh the scaffold, who sometime weeping, sometime crying out aloud, and continually crossing themselves, prayed in Latin, crossing them with her hand bade them farewell, and wishing them to pray for her even until the last hour. This done, one of the women have a Corpus Christi cloth lapped up three-corner-ways, kissing it, put it over the Queen of Scots’ face, and pinned it fast to the caule of her head. Then the two women departed from her, and she kneeling down upon the cushion most resolutely, and without any token or fear of death, she spake aloud this Psalm in Latin, In Te Domine confido, non confundar in eternam, etc. Then, groping for the block, she laid down her head, putting her chin over the block with both her hands, which, holding there still, had been cut off had they not been espied. Then lying upon the block most quietly, and stretching out her arms cried, In manus tuas, Domine, etc., three or four times. Then she, lying very still upon the block, one of the executioners holding her slightly with one of his hands, she endured two strokes of the other executioner with an axe, she making very small noise or none at all, and not stirring any part of her from the place where she lay: and so the executioner cut off her head, saving one little gristle, which being cut asunder, he lift up her head to the view of all the assembly and bade God save the Queen. Then, her dress of lawn [i.e. wig] from off her head, it appeared as grey as one of threescore and ten years old, polled very short, her face in a moment being so much altered from the form she had when she was alive, as few could remember her by her dead face. Her lips stirred up and a down a quarter of an hour after her head was cut off. Then Mr. Dean [Dr. Fletcher, Dean of Peterborough] said with a loud voice, ‘So perish all the Queen’s enemies’, and afterwards the Earl of Kent came to the dead body, and standing over it, with a loud voice said, ‘Such end of all the Queen’s and the Gospel’s enemies.’ Then one of the executioners, pulling off her garters,

espied her little dog which was crept under her cloths, which could not

be gotten forth by force, yet afterward would not depart from the dead

corpse, but came and lay between her head and her shoulders, which being

imbrued with her blood was carried away and washed, as all things else

were that had any blood was either burned or washed clean, and the executioners

sent away with money for their fees, not having any one thing that belonged

unto her. And so, every man being commanded out of the hall, except the

sheriff and his men, she was carried by them up into a great chamber lying

ready for the surgeons to embalm her.

|

|

By Conor Byrne Graduate of the University of Exeter and author of "Katherine Howard: A New History" and "Queenship in England", both published by MadeGlobal. I specialise in late medieval and early modern queenship.  On

a midsummer day in late June, the former queen of France lay dying at

her residence of Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk. Mary Tudor, the universally

acknowledged beautiful younger sister of Henry VIII, was only

thirty-seven years of age at the time of her death. Fiery, charismatic

and passionate, Mary is perhaps better known for being the beautiful

duchess of Suffolk rather than queen of France, a position she occupied

for only three months. The 'white queen', as Mary has sometimes been

known, was surrounded by only a few attendants in the gentle seclusion

of her Suffolk estate. It is entirely possible that her husband was not

at her side in her last hours. On

a midsummer day in late June, the former queen of France lay dying at

her residence of Westhorpe Hall in Suffolk. Mary Tudor, the universally

acknowledged beautiful younger sister of Henry VIII, was only

thirty-seven years of age at the time of her death. Fiery, charismatic

and passionate, Mary is perhaps better known for being the beautiful

duchess of Suffolk rather than queen of France, a position she occupied

for only three months. The 'white queen', as Mary has sometimes been

known, was surrounded by only a few attendants in the gentle seclusion

of her Suffolk estate. It is entirely possible that her husband was not

at her side in her last hours. In her youth, Mary had been described as 'a Paradise - tall, slender, grey-eyed, possessing an extreme pallor'. She was born at the palace of Sheen in March 1496, the youngest surviving child of Henry VII and Elizabeth of York. When she was only six years old, her eldest brother Arthur died and her mother followed Arthur to the grave only ten months later. Mary appears to have been close with her brother Henry, later Henry VIII. He was to name his only surviving child after her, a princess born in 1516. Mary had been married to Charles, duke of Suffolk since May 1515. Their marriage had scandalised Europe and had outraged King Henry, who was furious with the couple's failure to secure royal permission for their marriage. The couple were fortunate to escape with a heavy fine: by the standards of the time, Henry's honour had been disparaged by his sister's actions, and her husband the duke could have been imprisoned or even executed. Although the king and his younger sister had traditionally been close, their relationship was further strained after 1527, when Henry pursued marriage with Anne Boleyn. Mary was close to his wife, Katherine of Aragon, whom she had known since her early years. As David Loades writes, Mary and Anne 'exchanged insults of a semi-public nature'. Henry's annoyance with his sister's behaviour means that he seems to have failed to mourn her death. He left no comment when informed of her demise, although this reaction is perhaps explained by the fact that he had just remarried and was spending time with his new consort. Mary's widower, Charles Brandon, was left with three children: Frances (born in 1517; she married Henry Grey the same year); Eleanor (born in 1519); and Henry (who was to die the following year). Less than three months after his wife's passing, the duke remarried. His second wife was fourteen-year-old Katherine Willoughby. The thirty-five year age difference between the duke and his teenage bride did not pass without comment, but the marriage was a successful one. In the story of the early Tudors, Mary tends to be overshadowed by her volatile brother and the drama of his six marriages. Yet she was a passionate, intelligent and charismatic woman who was a teenaged Queen of France and who caused considerable controversy when she decided to marry her husband's favourite without seeking royal permission. Two decades after Mary's death, her granddaughter Lady Jane Grey briefly became queen of England, an event that Mary could never have foreseen. The Death of Mary Tudor, Queen of France - By Conor Byrne |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Webpage © 1995-2017 Isle of Standauffish