|

Some Insights from an Expert Lan Fleming Summary

In

a discussion with a NASA aerospace engineer familiar with the space shuttle

reaction control system, I learned that the thrusters never generate any

light while operating, but they always emit a small cloud of unburned propellant

just before the thruster fires and a much larger cloud immediately after

the thruster shuts down. The post-burn cloud may be visible, but only when

reflecting sunlight. The pre-burn cloud is never visible to the human eye

but might be detected by a light-sensitive camera. Any light flashes seen

in space shuttle videos cannot be from a thruster unless they coincide

with the beginning or end of a rocket burn. The consequences of this information

in regard to two videos of apparently anomalous objects taken by shuttle

video cameras are described.

Introduction

As

described in previous articles here and elsewhere, several objects in the

STS-48 video of Sept. 15, 1991 seem to react to a flash of light by changing

course. According to James Oberg and others associated with NASA, the flash

of light was caused by the firing of a small reaction control system (RCS)

thruster on the space shuttle. Oberg has asserted that:

The

RCS jets usually fire in 80-millisecond pulses to keep the shuttle pointed

in a desired direction, under autopilot control (usually once every few

minutes). These jets may flash when they ignite if the mixture ratio is

not quite right. Propellant also tends to seep out the feed lines into

the nozzle, where it accumulates, freezes through evaporative cooling,

and flakes off during the next firing. The ejected burn byproducts travel

at about 1000 ft/sec. One pulse usually emits about a quarter pound of

propellant in a fan-shaped plume.

While

I've written several articles pointing out flaws in the interpretation

of the light flash in the STS-48 video as the product of a thruster firing,

I had no reason to question the above description of thruster operation

because Oberg had a long career as a flight officer in the Mission Control

Center at Johnson Space Center, and frequently appears as an expert on

spaceflight for TV news and on the lecture circuit. But it turns out his

description is wrong or at least misleading on several important points.

I

recently had the opportunity to discuss various aspects of the space shuttle's

RCS propellant supply system with a NASA aerospace engineer who was involved

in the design, testing, and performance evaluation of the RCS from the

nearly the beginning of the shuttle program. Unlike Oberg, this engineer

observed tests of thruster firings close up on a routine basis. Most of

our discussions were related to work I am doing and was focused on the

ingenious system that dependably supplies fuel and oxidizer to the rockets

under weightless conditions in space as well under Earth's gravity during

reentry. However, he also described what happens on the business end of

an RCS thruster when it fires.

RCS

Propellant Behavior Before, During, and After a Thruster Burn

All

of the space shuttle's rocket engines use the same "hypergolic" propellants,

meaning two different chemical compounds that ignite on contact without

the need of any ignition source such as an electrical spark. The fuel is

monomethyl hydrazine (MMH) and the oxidizer is nitrogen tetroxide (NTO).

This is fairly common knowledge and can be found on many web sites

The

important fact about the RCS thrusters that I learned from the NASA engineer

is that the two valves that simultaneously open to admit MMH and NTO into

the rocket combustion chamber are not located immediately next to the combustion

chamber walls. The valve mechanisms cannot withstand the intense heat generated

by combustion(about 3500¡ Celsius). So the valves are mounted on

a "thermal standoff" plate some distance from the combustion chamber and

are connected to it by tubing, as shown in the diagram of a vernier RCS

thruster in Figure 1.

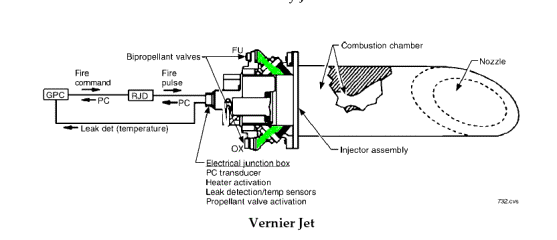

Figure

1: Diagram of a vernier reaction control thruster of the type alleged to

have fired to cause object motions in the STS-48 video. The green regions

indicate the "dribble volume," which is the section of tubing between either

of the propellant valves and the combustion chamber.

When

the thruster starts firing, the propellants are briefly exposed to the

vacuum of space after flowing out of the opened valves until they reach

the combustion chamber and ignite.While exposed to vacuum, some of the

liquid propellants boils off into space and then immediately freezes into

"microscopic snow," as this engineer called it. In the case of the small

thrusters, this happens so quickly over the short distance from the valve

to the combustion chamber(about 2 inches) that the amount of "snow" generated

is too small to be seen.

When

the valves are closed to shut the thruster down, small amounts of propellant

are trapped in the tubes between the valves and the combustion chamber.The

engineer called this volume of trapped propellant the "dribble volume,"

perhaps because it was observed to just dribble out of the thruster after

shutoff during ground testing under atmospheric pressure. But in the vacuum

of space, the "microscopic snow" also forms after shutoff just as it does

at startup. But the dribble volume is large enough that the snow generated

can be seen as a white plume in reflected sunlight. It is totally

invisible without some external source of illumination.

The

claim that significantly more unburned propellant is expelled at the end

of a thruster burn than at the beginning appears to be supported by the

telemetry records for the combustion chamber pressures of the Discovery's

thrusters during the STS-48 mission, which I obtained from the NASA FOIA

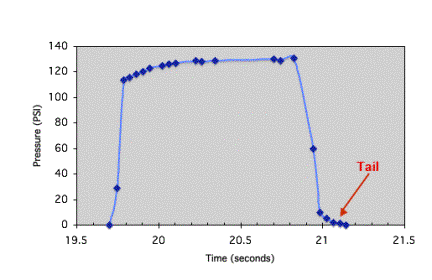

office.Figure 2 shows a plot of the combustion chamber pressure versus

time for the thruster burn proposed as the cause of the light flash in

the STS-48 video. At the beginning of the burn, the pressure quickly rises

from 0 (vacuum) to 110 psi, but after the thruster is shut off, the pressure

stops its rapid decline and tails (or dribbles) off again to zero. This

tail region evidently is the pressure generated by the unburned liquid

propellant trapped in the "dribble volume" evaporating into space. The

record of STS-48 thruster firings I have is for a time period of 45 minutes

with many burns recorded for all of the shuttle's vernier RCS thrusters,

and every single one of them has the same steep rise at ignition and the

same small "tail" after shutoff. Since it is a feature of every thruster

firing, an associated emission of a visible plume of propellants is most

likely to be present, too.

Figure

2: Plot of combustion chamber pressure versus time for the firing of the

L5D vernier thruster proposed as the source of the light flash seen in

the STS-48 video on Day 2, 21:28:19.5 Mission Elapsed Time.

The

engineer likened the plume of small ice particles to the smoke that pours

out of the barrel of a gun after the muzzle flash. Then he added "but

there is no 'thruster' flash." Quite to the contrary of what might

be construed from Oberg's assertion, there is no "flash" in the sense that

the propellant itself generates little if any light at all during a burn.

The unburned liquid propellant can be said "flash" to a vapor after thruster

shutoff, but this refers only to the rapid phase change from liquid to

gas, not to light emission. While Oberg may have been aware of this fact,

his description was unclear about the meaning of the word"flash" and I

doubt the meaning was apparent to many of his readers.

Mr.

Oberg has asserted that:

It

should also be pointed out that as all experienced observers of shuttle

TV images realize, the visible flare of these jet firings is only an occasional

and sporadic feature of their actual firings, which at other times -- especially

in periods of smooth, stable propellant flow -- can be invisible.

The

evidence of the combustion chamber pressures indicates that there is nothing

at all "sporadic" about this phenomenon. The numerous photos of shuttle

thrusters emitting plumes provide more evidence that they are predictable

result of a thruster shutoff. I have been puzzled for a long time about

why the rocket combustion gases were so easy to see when they are supposed

to be nearly invisible. The puzzle is apparently solved: these photos show

jets of microscopic snow at the end of the firing cycle in reflected sunlight.

In Figure 3, plumes from two primary RCS rockets on the left can clearly

be seen. The dull reddish glow on the right is apparently from an aft-firing

primary thruster, making a total of three thrusters simultaneously emitting

plumes of what must be unburned propellant – an unlikely coincidence if

such emissions were sporadic rather than routine consequences of thruster

firings.

Figure

3: Photograph showing plumes of unburned propellant emitted by three RCS

thrusts simultaneously.

In

the event that there is any instability during a thruster firing that causes

the fuel-to-oxidizer ratio to be out of balance, the unburned propellant

would be unlikely to form snow as it exits. According to one reference,

"Hydrazine ... is technically stable to about 250 C."At the 3500 C temperatures

in an RCS combustion chamber, any excess MMH fuel would be converted to

a gas, decompose into simpler component gases such as water and methane,

and finally exit the thruster nozzle unseen along with the combustion products.

A

blockage of propellant flow long enough to intermittently halt combustion

and cause "snow" to be generated in mid-burn could be extremely

dangerous, according to the NASA engineer. If the thruster were not shut

down immediately, such a malfunction could potentially lead to an explosion

and even loss of the vehicle.

In

the light of this new information, it seems that several things that have

been written about the STS-48 video have to be reconsidered concerning

the behavior of space shuttle thrusters. Another video taken during the

more recent STS-102 mission also is reexamined here because of its similarities

with the STS-48 video.

STS-48

A

time-lapse composite of video frames before and after the light flash is

shown in Figure 4. Several objects move almost immediately when the light

flash occurs. Their position at the time of the flash is indicated by the

red dots in the image. The light flash and movements of the objects has

been attributed to the orbiter's L5D thruster (left side firing down).

Figure

4: Time-lapse image of objects in the STS-48 video created from a composite

of video frames spaced at 1-second intervals.

Since

there was no serious malfunction during the STS-48 mission, if the light

flash observed were from the L5D thruster, it could only mark the end of

the thruster burn, not the beginning. Figure 5 shows a graph I made for

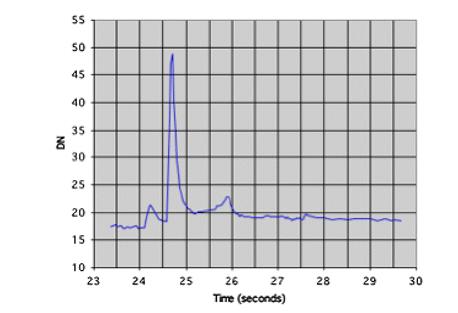

an earlier article concerning this light flash. There is a faint "pre-flash"

that might seem to fill the role of a very brief jet of "snow" at the start

of the thruster firing, assuming the camera, which was set to for low light

levels, could detect light that is too faint to be perceived by the human

eye.The pre-flash occurs 0.4 seconds before bright "main flash" that seems

to have caused the objects in the video to move. But the L5D thruster firing

supposedly responsible for the flash was 1.2 seconds in duration, so the

pre- and post-burn flashes should have been 1.2 seconds apart, not 0.4

seconds. Worse for the thruster theory, the exhaust exits the nozzle at

a speed of 3500 meters per second. If it is assumed that the exhaust plume

hit the objects just as the thruster shut down, the objects would have

to be over 4 kilometers away from the shuttle, since that is the distance

the exhaust plume would travel in 1.2 seconds before impinging on the objects.

Figure

5: STS-48 video average frame brightness over seven seconds plotted at

1/30-second intervals. Start time corresponds to the video display clock

time of 20:39:23.Objects in the video changed course at the time of the

highest intensity peak in this graph.

There

is a third pulse that occurs roughly 1.3 seconds after the main flash that

might be suspected to be the rocket's shutdown flash, but again it is much

fainter than the main flash, which shouldn't be the case if the third pulse

was the light from the dribble volume of fuel escaping after thruster shutdown.

And there should be only one or two light pulses, not three.

However,

a post-burn jet of "snow" might explain one seemingly anomalous characteristic

of the light flash I noted in my previous article: the three light pulses

occurred during a period of elevated background brightness in the image

that lasted for at least 5 seconds, which is much longer than the 1.2-second

duration of the thruster firing. The jet of snow at shutdown probably travels

at a much slower rate than the 3500m/sec speed of the (invisible) plume

of combustion products during the thruster burn. Moving at a slower rate,

it would disperse much more slowly than combustion products and thus linger

as a diffuse cloud, perhaps reflecting enough sunlight to raise the background

brightness for several seconds. So this one characteristic of the post-burn

plume from the thruster might support the thruster hypothesis. But all

its other characteristics make the thruster hypothesis seem even more preposterous

than it did when I wrote the earlier article, which assumed that thrusters

can "flare up" sporadically, as Oberg would have it.

STS-102

The

relationship between thruster firings and "flashes" of light reflected

from unburned combustion products also has relevance to a video taken during

Space Shuttle Discovery's STS-102 mission in March 2001.As in the STS-48

video, a light flash occurs in the STS-102 video and a slow-moving object

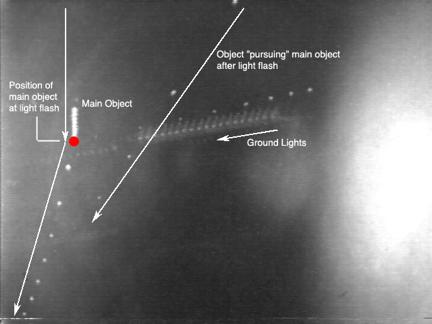

abruptly changes course. This is shown in the time-lapse composite of Figure

6. Another object appears at the top of the frame and seems to pursue the

slower-moving "main" object. A high-speed object also appeared to be pursuing

Object M1 in the STS-48 video, but was moving too fast to be captured in

the time-lapse image of Figure 4.

Figure

6: Time exposure overlay of frames at 1-second intervals from STS-102 video.

The red shows the position of the object when the light flash occurs.

In

a previous article I noted that the time display in the Mission Control

Room, which appeared briefly in the STS-102 video, indicated that the light

flash occurred at least 5 seconds before the closest thruster firing, which

occurred at 12:30:39 GMT.Since it is impossible for the thruster firing

to be the cause of an event that preceded it in time, it could not have

been the cause of the light flash – assuming the mission control time display

was accurate.

Another

event occurred in the STS-102 video that has been suggested as support

for the "prosaic" thruster hypothesis.This event was a second flash of

light that occurred 1.3 seconds after the first flash. As it happens, 1.3

seconds was also the amount of time that elapsed between the start of the

12:30:39 firing suspected to be associated with the light flash and the

next firing at 12:30:40.3. While I assumed this was probably a random coincidence,

the argument has been made that the elapsed times are the same because

the flashes came from the thruster at the beginnings of the two

firings. But as previously noted, the NASA engineer said that the visible

plumes of unburned propellant come at the end of a thruster firing

and not at the beginning. In this case, the elapsed time between the end

of the first and second firings was 0.96 seconds (12:30:39.548 GMT and

12:39:40.508 GMT) – significantly less than the 1.3 seconds between the

observed light flashes.

The

elapsed time between the end of the first and second thruster firings does

not agree with the elapsed time between the first and second light flash,

assuming the visible flashes mark thruster shutoff, as the NASA engineer

asserted. In that case, a rocket firing can be ruled out as the cause of

the object's motion in the STS-102.

Even

if it is assumed that the light pulses come at both the beginning and the

end of a thruster burn and that the startup pulse can be brighter than

the shutoff pulse, Figure 7 shows the actual brightness curve still cannot

be matched to a thruster firing. The first peak at time A (when the "main

object" in the video changes course) might correspond to the startup pulse

of the thruster burn and the second peak at time B might correspond to

the "shutoff" pulse. But the peak at B would be 0.37 seconds into the 0.48-second

burn, assuming it started at time A in Figure 7. This would indicate the

burn was prematurely interrupted and that a "snow" of unburned propellant

was being expelled from the thruster rather than the hot gases of combustion

more than 1/10 of a second before the intended thruster shutoff. Such a

premature interruption of the firing could signal a potentially serious

problem with the propellant supply, such as the ingestion by the thruster

of a large bubble of helium. Helium is the gas that is used to pressurize

the propellant so that it will flow to the thruster immediately when the

fuel and oxidizer valves are opened. A small amount of helium is always

in solution with the liquid propellants, but it is never supposed to form

large gas bubbles in the propellant lines.

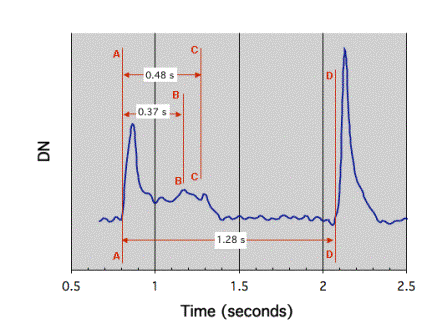

Figure

7: STS-102 video average frame brightness over 2 seconds plotted at 1/30-second

intervals. The length of time from A to D is close to the 1.28-seconds

between documented thruster burns. The length of time between A and C is

the duration of the first thruster burn assumed to start at time A. The

rise in brightness to the peak near B might seem to correspond to the first

burn's "shutoff" light pulse but that peak comes a tenth of a second before

the assumed shutoff time.

Conclusion

There

are only two cases that I know of in which objects in a space shuttle video

react to a light flash with a radical change in course: STS-48 and STS-102.

The information I've received from an expert in the shuttle's RCS propulsion

system provides a compelling refutation of Oberg's argument that thruster

firings were the cause of the objects' behavior in both cases.

Another

assertion by Oberg that is incorrect is that propellant seeping out of

propellant lines and freezing in the nozzle is a routine occurrence on

the orbiter. To the contrary, it is an indication of a potentially serious

leak according to the NASA engineer. If such a leak is detected the caution

and warning system notifies the crew that a "Fail-Leak" condition has occurred.

The leaking thruster is then isolated by shutting valves upstream of the

leak. There is no record that I know of that any such failure occurred

during either STS-48 or STS-102, at least during the time when the videos

were taken. Based on Oberg's statements, it had seemed to me that in both

the STS-48 and STS-102 videos the high-speed "projectiles" seemingly pursuing

slower-moving objects might be explained as ice chunks expelled from the

nozzle during the rocket burn. But as the presence of such ice in the thruster

would indicate a possibly serious problem with the shuttle propulsion system,

this explanation no longer seems feasible.

Finally,

Oberg stated that the speed of the RCS rocket exhaust gases is about 1000

feet per second. Their actual speed is 3500 meters or 11,482 feet per second.

That is ten times faster than the speed he cited. This error is of no great

importance to the question of apparent anomalous objects in shuttle videos.

But it is one more indication that while Oberg may well be an expert on

many aspects of space flight, he evidently has no particular expertise

or experience with the RCS propulsion system.

While

the NASA engineer I spoke with was a legitimate authority on the space

shuttle's RCS rockets, it should be apparent from reading this article

that I have not simply made an appeal to authority here just because what

he said severely undermines the "prosaic" explanations for these space

shuttle videos. Instead, I've tried to verify his assertions to the extent

feasible by checking independent references and data sources such as the

RCS combustion chamber pressure records for STS-48. Everything I've found

was consistent with what he told me.

The brightness curves for both the STS-48 and the STS-102 videos do not match what would be expected for reflected light from unburned RCS propellant if it is assumed that the light flash comes only at the end of a thruster burn as asserted by the NASA engineer I discussed the question with. Even if it is assumed that a light flash can be detected at the beginning of a thruster firing by a light-sensitive camera, the brightness curves in both videos still do not match what would be expected for a thruster burn. |