|

|

Satellite captures enormous 90-mile-wide storm that's UNDERWATER

UPDATED: 09:38 EDT, 21 February 2012 A Nasa satellite has provided jaw-dropping pictures of a huge 'storm' brewing under the sea.

The swirling mass of water - which measures a whopping 93 miles wide - has been spotted off the coast of South Africa by the Terra satellite on December 26. But there's no need to alert international shipping, or worry about the poor fish that might find themselves in an endless washing cycle - the body of water poses no threat. Stunning image: The 90-mile-wide whirlpool, spotted off the coast of South Africa

by Nasa's Terra satellite, looks deadly but it more likely to create life by lifting nutrients from the ocean floor Indeed, it is more likely to create

life by sucking nutrients from the bed and bringing them to the surface.

The sea storms - which are better known as eddies - form bizarre whirl

shaped shapes deep beneath the ocean's surface. This counter-clockwise

eddy is thought to have peeled off from the Agulhas Current, which flows

along the southeastern coast of Africa and around the tip of South

Africa.

Closer look: A detail from the Terra photo shows the eddy is turning counter-clockwise -

with the water surrounding it becoming a deeper blue the further it is from the centre Agulhas eddies - also called 'current

rings' - tend to be among the largest in the world, transporting warm,

salty water from the Indian Ocean to the South Atlantic.

Agulhas eddies can remove juvenile fish from the continental shelf, reducing catch sizes if one passes through a fishing region. The bizarre phenomenon was spotted when the Terra satellite was conducting a routine natural-colour image of the Earth. SOURCE: DAILY MAIL |

|

|

|

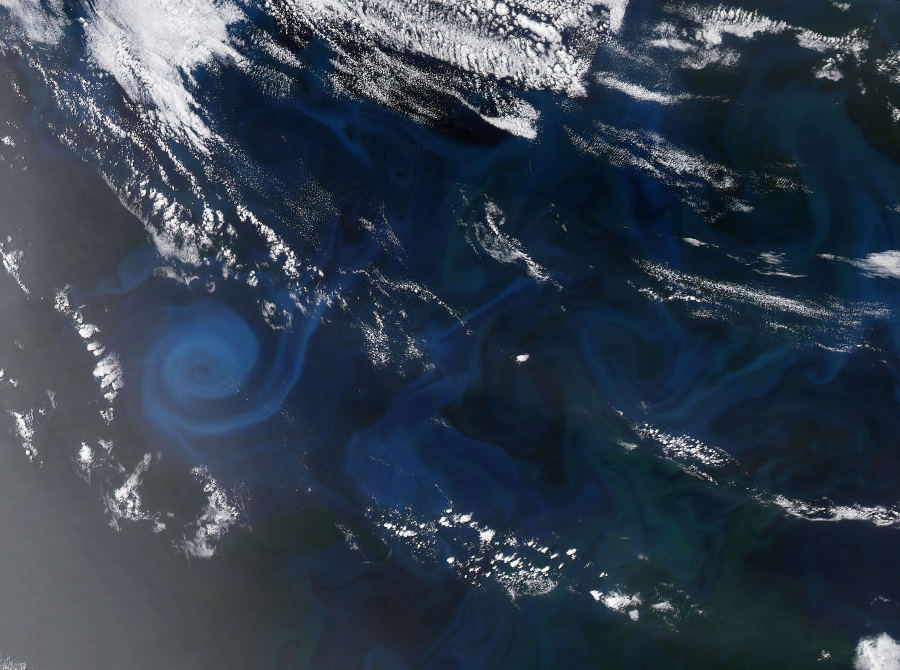

Spiral of Plankton

Credit: NASA Earth Observatory acquired December 30, 2013 Full Size Image While the northern latitudes are

bathed in the dull colors and light of mid-winter, the waters of the

southern hemisphere are alive with mid-summer blooms. The Moderate

Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite

acquired this natural-color satellite image of a plankton bloom as it

appeared at 1:05 p.m. local time on December 30, 2013. The eddy is

centered at roughly 40° South latitude and 120° East longitude, about

600 kilometers off the coast of Australia in the southeastern Indian

Ocean.

Like land-based plants, phytoplankton require sunlight, water, and nutrients to grow. Sunlight is now abundant in the far southern latitudes, so nutrients are the limiting variable to phytoplankton growth. Open waters of the ocean can appear relatively barren compared to the nutrient-rich waters near the world’s coasts. In the case of the bloom above, the nutrients may have been supplied by the churning action of ocean currents. As the close-up image shows, an eddy is outlined by a milky green phytoplankton bloom. Eddies are masses of water that typically spin off of larger currents and rotate in whirlpool-like fashion. They can stretch for hundreds of kilometers and last for months. As these water masses stir the ocean, they can draw nutrients up from the deep, fertilizing the surface waters to create blooms in the open ocean. Other times, they carry in nutrients spun off of other currents. It is possible that the mesoscale eddy and plankton bloom shown above are related to the “great southern coccolithophore belt” (or the “great calcite belt.”) In late southern spring and summer (roughly November to March), satellite instruments detect an abundance of particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) in waters at high latitudes. The PIC is often due to calcium carbonate, which makes up the plate-like shells of microscopic plankton known as coccolithophores. The calcium carbonate gives the water a chalky aquamarine hue. References:

Aqua - MODIS SOURCE: NASA Earth Observatory While the northern latitudes are bathed in the dull colors and

light of mid-winter, the waters of the southern hemisphere are alive

with mid-summer blooms. The Moderate Resolution Imaging

Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite acquired this

natural-color satellite image of a plankton bloom as it appeared at 1:05

p.m. local time on December 30, 2013. The eddy is centered at roughly

40° South latitude and 120° East longitude, about 600 kilometers off the

coast of Australia in the southeastern Indian Ocean.

Like land-based plants, phytoplankton require sunlight, water, and nutrients to grow. Sunlight is now abundant in the far southern latitudes, so nutrients are the limiting variable to phytoplankton growth. Open waters of the ocean can appear relatively barren compared to the nutrient-rich waters near the world’s coasts. In the case of the bloom above, the nutrients may have been supplied by the churning action of ocean currents. As this image shows, an eddy is outlined by a milky green phytoplankton bloom. Eddies are masses of water that typically spin off of larger currents and rotate in whirlpool-like fashion. They can stretch for hundreds of kilometers and last for months. As these water masses stir the ocean, they can draw nutrients up from the deep, fertilizing the surface waters to create blooms in the open ocean. Other times, they carry in nutrients spun off of other currents. It is possible that the mesoscale eddy and plankton bloom shown above are related to the “great southern coccolithophore belt” (or the “great calcite belt.”) In late southern spring and summer (roughly November to March), satellite instruments detect an abundance of particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) in waters at high latitudes. The PIC is often due to calcium carbonate, which makes up the plate-like shells of microscopic plankton known as coccolithophores. The calcium carbonate gives the water a chalky aquamarine hue. Image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, NASA Earth Observatory, using data from the Land Atmosphere Near real-time Capability for EOS (LANCE). Caption by Michael Carlowicz, NASA Earth Observatory, with image interpretation help from Norman Kuring, NASA Ocean Color Group. SOURCE: NASA AQUA Project Science |

|

FAIR USE

NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the

use of which has not been specifically authorized by

the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium

distributes this material without profit to those who

have expressed a prior interest in receiving the

included information for research and educational

purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of

any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17

U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material

from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond

fair use, you must obtain permission from the

copyright owner.

All material on these pages, unless

otherwise noted, is © Pegasus Research Consortium 2001-2019 |

Webpages © 2001-2019 Pegasus Research Consortium |