|

Mars on Earth |

||||

|

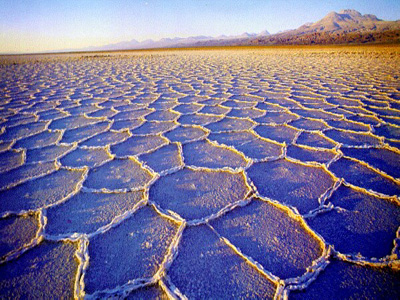

Atacama Desert, Chile ..

Photograph of hyperarid, plantless core of the Atacama Desert (987 meters above sea level) about 80 km southeast of the Chilean port of Antofagasta. Despite the absence of plants and the estimate of actual rainfall only once every other decade, soil samples taken at 20 to 30-cm depth at this site yielded counts of culturable soil bacteria on the order of 100,000 colony forming units (cfu) per gram of dry soil. Bacterial DNA was successfully extracted from the soil sample; researchers speculate that bacterial communities in such an absolute desert could lie dormant until activated by the unlikely rain event every few decades. Julio

Betancourt, USGS, Desert

Laboratory, Tucson AZ

Text by Mari

N. Jensen, University

of Arizona News Services

A place so barren that NASA uses it as a model for the Martian environment, Chile's Atacama desert gets rain maybe once a decade. In 2003, scientists reported that the driest Atacama soils were sterile. Not so, reports a team of Arizona scientists. Bleak though it may be, microbial life lurks beneath the arid surface of the Atacama's absolute desert. "We found life, we can culture it, and we can extract and look at its DNA," said Raina Maier, a professor of soil, water and environmental science at the University of Arizona in Tucson. The work from her team contradicts last year's widely reported study that asserted the "Mars-like soils" of the Atacama's core were the equivalent of the "dry limit of microbial life." Maier said, "We are saying, 'What is the dry limit of life?' We haven't reached it yet." The Arizona researchers will publish their findings as a letter in the Nov. 19 issue of the journal Science. Maier's co-authors include UA researchers Kevin Drees, Julie Neilson, David Henderson and Jay Quade and U.S. Geological Survey paleoecologist Julio Betancourt. The project was funded by the National Science Foundation and the National Institute for Environmental and Health Sciences, part of the National Institutes of Health. The project began not as a search for current life but rather as an attempt to peer into the past and reconstruct the history of the region's plant communities. Betancourt and Quade, a UA professor of geosciences, have been conducting research in the Atacama for the past seven years. Some parts of the Atacama have vegetation, but the absolute desert of the Atacama's core -- an area Betancourt describes as "just dirt and rocks" -- has none. Nor does the area have cliffs which harbor ancient piles of vegetation, known as middens, collected and stored by long-gone rodents. Researchers use such fossil plant remains to tell what grew in a place long ago. So to figure out whether the area had ever been vegetated, Quade and Betancourt had to search the soil for biologically produced minerals such as carbonates. To rule out the possibility that such soil minerals were being produced by present-day microorganisms, the two geoscientists teamed up with UA environmental microbiologist Maier. In October of 2002, the researchers collected sterile soil samples along a 200-kilometer (120 miles) transect that ran from an elevation of 4,500 meters (almost 15,000 feet) to sea level. Every 300 meters (about 1,000 feet) along the transect, the team dug a pit and took two soil samples from a depth of 20 to 30 centimeters (8 to 12 inches). To ensure the sample was sterile, every time he took the sample, Betancourt had to clean his hand trowel with Lysol. "When it's still, it's not a problem," he said. "But when the wind's blowing at 40 miles per hour, it's a little more complicated." The geoscientists brought their test tubes full of desert soil back to Maier's lab, where her team wetted the soil samples with sterile water, let them sit for 10 days, and then grew bacteria from them. "We brought 'em back alive, it turns out," Betancourt said. ..

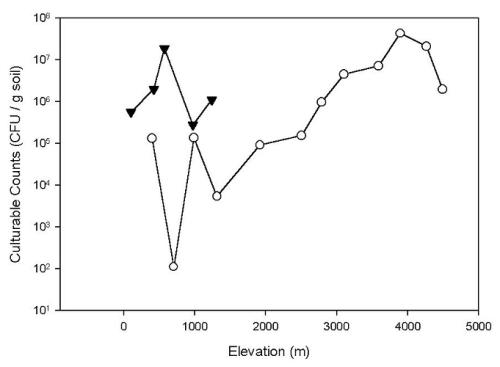

Graph showing counts of culturable soil bacteria (cfu) per gram of dry soil sampled at 20 to 30 cm depth along 4500-m and a 1200-m elevational transects in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile (at ~24 degrees South). The 4500-m transect (the open circles) started in Andean steppe grasslands on the flanks of Volcan Llullaillaco, the second highest volcano in the world, and traverses large stretches of absolute desert that support no plants and go several years or decades without any rain. Vegetation on open terrain along this transects occurs above 3500 m, though in wet years annual blooms can extend a few hundred meters below that. The 1200-m transect (the closed triangles) crosses "lomas" plant communities supported by permanent fog banks on steep escarpments and canyons near the Pacific coast. Clearly, soil bacterial counts are two to three orders of magnitude where there is vegetation than where there is none. The important point, however, is that in the extreme absolute desert there are soil bacteria at all. Maier and her team have not yet identified the bacteria that come from the extremely arid environment of the Atacama's core. She can say they are unusual. She said, "As a microbiologist, I am interested in how these microbial communities evolve and respond. Can we discover new microbial activities in such extreme environments? Are those activities something we can exploit?" The team's findings suggest that how researchers look for life on Mars may affect whether life is found on the Red Planet. The other researchers who had tested soil from the Atacama had looked for life only down to the depth of four inches. So one rule, Quade quipped, is, "Don't just scratch the surface." Saying that Mars researchers are most likely looking for a needle in a very large haystack, Maier said, "If you aren't very careful about your Mars protocol, you could miss life that's there." Peter H. Smith, the UA planetary scientist who is the principal investigator for the upcoming Phoenix mission to Mars, said, "Scientists on the Phoenix Mission suspect that there are regions on Mars, arid like the Atacama Desert in Chile, that are conducive to microbial life." He added, "We will attempt an experiment similar to Maier's group on Mars during the summer of 2008." As for Maier and her colleagues, Betancourt said, "We're very, very interested in life on Earth and how it functions." Maier suspects the microbes may persist in a state of suspended animation during the Atacama Desert's multi-decadal dry spells. So the team's next step is to return to Chile and do experiments on-site. One option is what Maier calls "making our own rainfall event" -- adding water to the Atacama's soils -- and seeing whether the team could then detect microbial activity. Maier, R. M., Drees, K. P., Neilson, J. W., Henderson, D. A., Quade, J. and Betancourt, J.L. 2004. Microbial Life in the Atacama Desert. Science 306: 1280. For more

information contact:

US Department

of the Interior

| US Geological Survey

|

||||

| Related Links: Papers - PDF | ||||

|

Atacama Desert, Chile ..

The actual study of Mars can take place incredibly close to home when compared with the distance from Earth to the planet. Just west of the Andes mountains in South America lies the 20 million-year-old Atacama Desert, where the dry atmosphere is the closest to that of Mars as it is possible to get here on Earth. Highly regarded by scientists and geographic researchers as the driest desert in the world, the Atacama plateau has had virtually no rainfall. This is due to its rain shadow, also known as a precipitation shadow, which means that the mountains block the passage of rain-producing weather systems, casting a "shadow" of dryness behind them. The desert plateau stretches an area of more than 966 km (600 miles), and is the perfect setting for scientists wishing to replicate experiments mimicking the environments of Mars. Layers upon layers of rock-hard sediment line the area, without any detectable signs of life. Even extremophiles - organisms known for surviving tough conditions such as thermal vents and hot springs - are nowhere to be found. It is these harsh conditions that create the perfect setting for scientists to link the similarities between these two closely related terrains, and conduct experiments that may reveal what happened to life on Mars. SOURCE: Discovery Channel |

||||

|

Atacama Desert, Chile ..

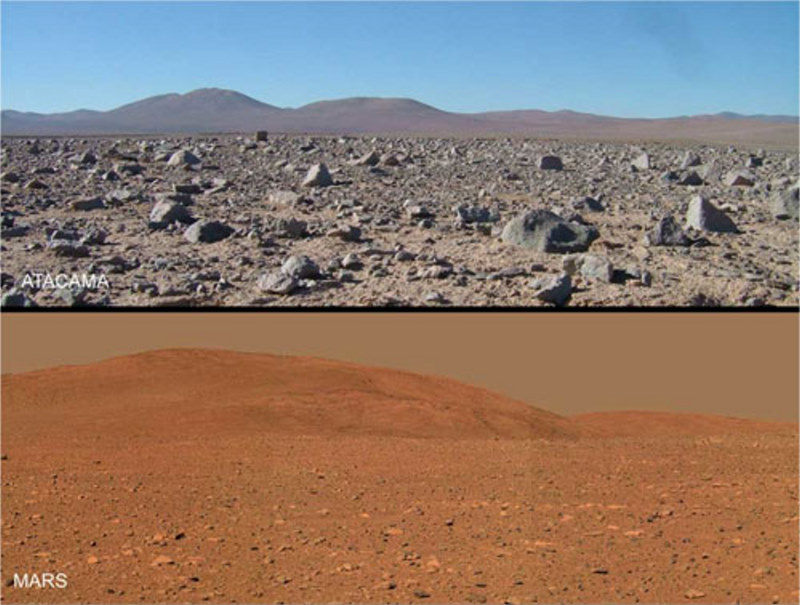

What are seven NASA Explorer School teachers doing in the Atacama desert in Chile? They are studying side-by-side with NASA scientists who search for life in extreme environments, closely approximating what they expect to find on other planets. Why the Atacama -- an inhospitable, seemingly lifeless, sun drenched spot that is probably the driest place on Earth? This natural environment on Earth poses some of the same challenges for human explorers as would a seemingly lifeless planet. NASA scientists and engineers need this type of landscape to test technology that will hopefully be used in places like the Moon or Mars.Join these seven teachers during their many adventures, as they experience authentic field research with world-renowned planetary scientists living and working in this remote Moon/Mars analog research site. At left you can see two comparative photos, one of Atacama and the other of Mars. Temperatures in the Atacama vary daily from 95oF down to 32oF.The ultimate goal of this excursion is to leverage these field expedition experiences into classroom use and to spread the word throughout the nationwide Explorer School network and beyond. SOURCE: NASA Atacama Field Expedition |

||||

|

..

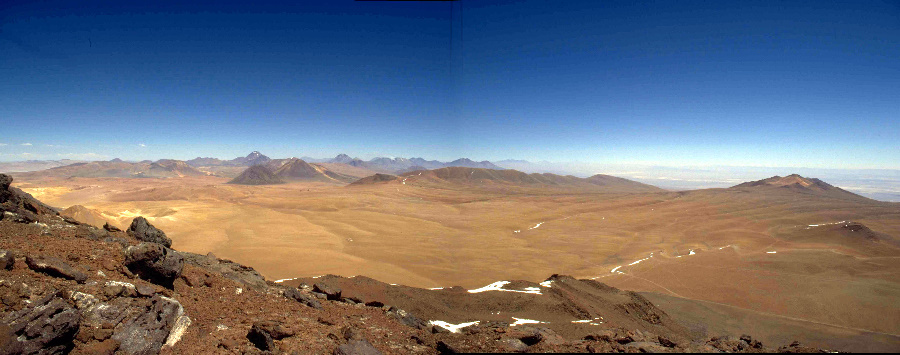

During 2007, I was on sabbatical leave (Caltech, Santa Barbara, Munich, etc.) working on theoretical models of early galaxy formation, reionization of the IGM, and the first and second-generation stars. I am also learning more about the scientific possibilities of long-wavelength observations in the far-infrared and sub-millimeter. These can be done at new facilities such as those on the Atacama plateau in Chile (below) at high altitudes (16,000-17,000 ft) for observations of primordial gas and high-redshift galaxies. I also finished off a backlog of theoretical research and Hubble/FUSE (ultraviolet) observations on the structure, baryon content, and heavy-element abundances in the low-redshift intergalactic medium (IGM).

|

||||

|

Atacama Desert, Chile ..

..

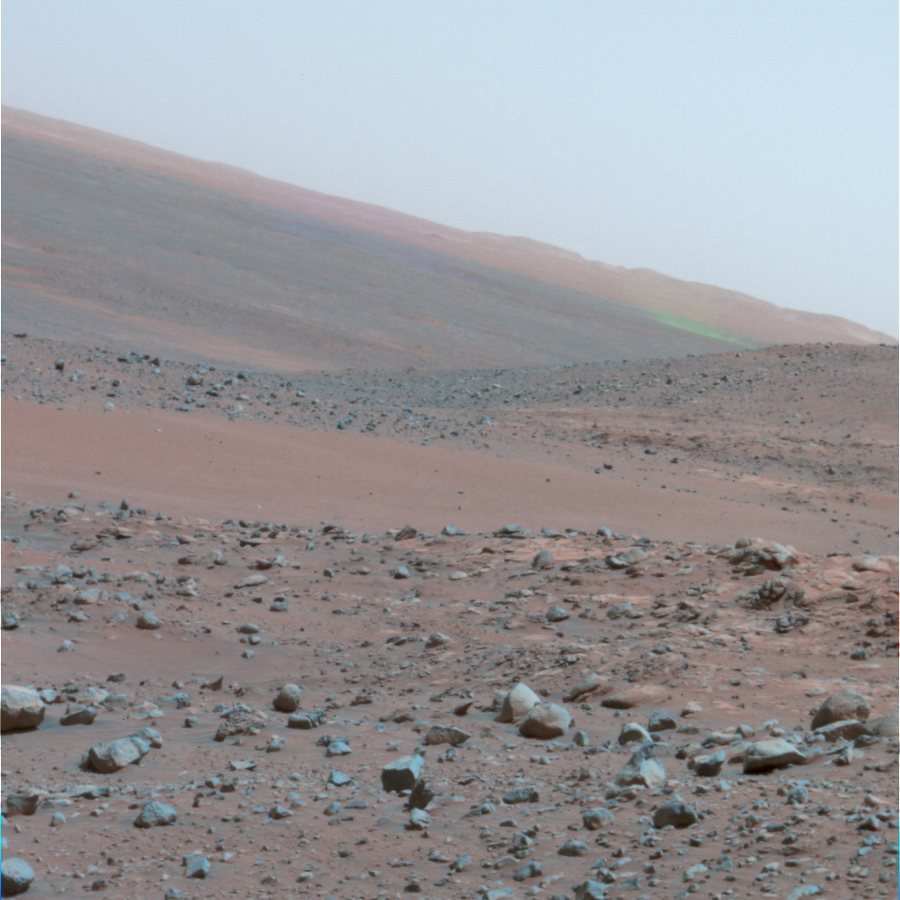

Scientists say something similar happened on Mars (right). Image credit: CNN This week at the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston, TX, NAI Co-I Nathalie Cabrol from the SETI Institute team presented results from the “Life in the Atacama” research expedition which took place in September and October of 2004. Sponsored by NASA’s Astrobiology Science and Technology for Exploring Planets (ASTEP) program, this expedition to the Chilean Atacama desert was designed to deploy a robotic rover and test its payload in search of microbial life, and beam data to a remote science team in Pittsburg. Samples first identified and documented by the remote science team using the rover showed positive identification of natural fluorescence of organic molecules including Chlorophyll and, after application of fluorescence dye probes, identification of DNA and protein. The rover’s exploration strategies were aimed at facilitating the detection of likely isolated and sheltered colonies of microbial life and could be used on Mars in future astrobiological missions. |

||||

|

..

..

..

... |

||||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | ||||

|

|