|

The Saga Of the Lost Space Tapes |

|

| NASA Is Stumped in Search For Videos of 1969 Moonwalk

By Marc Kaufman

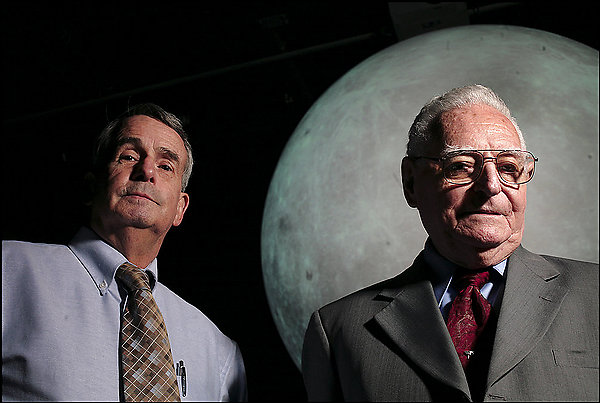

As Neil Armstrong prepared to take his "one small step" onto the moon in July 1969, a specially hardened video camera tucked into the lander's door clicked on to capture that first human contact with the lunar surface. The ghostly images of the astronaut's boot touching the soil record what may be the most iconic moment in NASA history, and a major milestone for mankind. Millions of television viewers around the world saw those fuzzy, moving images and were amazed, even mesmerized. What they didn't know was that the Apollo 11 camera had actually sent back video far crisper and more dramatic -- spectacular images that, remarkably, only a handful of people have ever seen. NASA engineers who did view them knew what the public was missing, but the relatively poor picture quality of the broadcast images never became an issue because the landing was such a triumph. The original, high-quality lunar tapes were soon stored and forgotten. Only in recent years was the agency reminded of what it once had -- clean and crisp first-man-on-the-moon video images that could be especially valuable now that NASA is planning a return trip. About 36 years after the tapes went into storage, NASA was suddenly eager to have them. There was just one problem: The tapes were nowhere to be found. What started as an informal search became an official hunt through archives, record centers and storage rooms throughout NASA facilities. Many months later, disappointed officials now report that the trail they followed has gone cold. Although the search continues, they acknowledge that the videos may be lost forever. "When we sent our camera up on the mission, everything about it was a first and a big unknown," said Richard Nafzger, an engineer with NASA who was involved in the original transmission of the Apollo 11 images to Earth and is now part of the search to find them. "Would the camera work? Would we get TV of that first step? We just didn't know what to expect. "In the same way, we're doing a kind of massive tape and document search that's never been done before," Nafzger said in a recent interview. "We might discover the tapes tomorrow, or we might reach a point where we have to say we can't go any further. Right now, I would have to tell you their fate is pretty much a mystery." Stanley Lebar, who had been in charge of developing the lunar camera, is also involved in the search. He can recite all the understandable reasons why he and his colleagues did not give the tapes the attention they deserved back in 1969 -- they were cumbersome, a highly specialized format that appeared to have limited value in the pre-digital age -- but he nonetheless is kicking himself now for not getting a copy for safekeeping. "We all understood the importance of this event to history, to posterity, and so we all should have made sure those tapes were safe and secure," said Lebar, 81. "I ask myself today, 'Why the heck didn't you think that way back then?' The answer is that I just assumed that NASA was going to do it. But, unfortunately, that was a bad assumption." The tale of the missing Apollo 11 tapes is made all

the more awkward because televised images of subsequent Apollo missions

were greatly improved. It was only for Apollo 11 that an unusually configured

video feed was used. It was transmitted from the moon to ground sites in

Australia and the Mojave Desert in California, where technicians reformatted

the video for broadcast and transmitted long-distance over analog lines

to Houston. A lot of video quality was lost during that process, turning

clear, bright images into gray blobs and oddly moving shapes -- what Lebar

now calls a "bastardized" version of the actual footage.

The original video from the moon was in an unconventional "slow-scan" format, made necessary because almost all of the broadcast spectrum was needed to send flight data to Earth. The format scanned only 30 percent of the normal frames per second, and it was done at a much lower than normal radio frequency. The images would probably have remained forgotten and of little consequence to Lebar, Nafzger and NASA but for the initiative of a retired California ground station engineer and several Australian technicians who meet regularly for reunions. In 2002, one of the men who had worked at Australia's Honeysuckle Creek ground station in 1969 -- and who had seen the high-quality Apollo 11 video originals back then -- found a 14-inch reel of tape in his garage that seemed to be from that period. He brought it to a Honeysuckle Creek reunion and passed it around. At the next year's reunion, several more Honeysuckle veterans brought in mementos from the Apollo era, and this time they included actual moonwalk photos they had taken as the video played on their special monitors. The photos were of the original images -- not the ones reformatted for television -- and they were clearly much better than what everyone else had seen. An American engineer had similar pictures taken at the Mojave site. The Australians were eager to learn whether the tape was of the actual Apollo 11 moonwalk, but they had no way to play the ungainly reels. Convinced that the tapes could have historical and educational value, they tracked down Nafzger, 66 -- one of the few Apollo 11-era people still working at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, where most Apollo data had been processed. The good luck continued when Nafzger found that the soon-to-be-mothballed Data Evaluation Lab at Goddard still had one of the few seven-foot-tall analog machines that could play the Apollo video. The Australians sent him the tapes and he put them into the recorder with great anticipation. But what came out was just chatter and computer data from an earlier Apollo mission. It was disappointing, but the seed had been planted: Not only was NASA reminded of the original moonwalk tapes, but the agency had a machine that could play them. It also had two men -- Nafzger and Lebar -- who still lived relatively close to Goddard and were willing to spend hours of their own time looking for the three hours of video. They spent weeks searching in the vast National Records Center in Suitland, where the tapes once were housed. They came up empty until finding documentation that some 26,000 boxes of Apollo tapes were requested by Goddard officials between the early 1970s and the early 1980s. Considering that the 45 videotapes from Apollo 11 would have been stored in just nine of those boxes, the odds against finding them were clearly daunting. Nonetheless, Nafzger and Lebar were optimistic. Back at Goddard, however, they found no trace of the missing tapes, nor of anyone who knew much about them. Clearly someone at Goddard had forwarded the Apollo tapes to other storage, dispersed them to other NASA centers or had them destroyed, but Nafzger and Lebar have had little luck identifying who that might be. The fact that all this happened about 30 years ago made the task more difficult, since some of the most likely decision makers are deceased. The missing tapes are now something of an embarrassment to NASA, which last August put Goddard's deputy director, Dolly Perkins, in charge of the search. She is overseeing the hunt for the tapes and, perhaps more important right now, for memos and directives that might yield clues to their fate. "As far as we know, all the tapes were handled properly from a mission perspective," she said. "Typically, when we record at a ground site, we don't preserve data tapes. The scientific investigators will get what they need and then erase. But here there is some indication that we didn't destroy the tapes but stored them for some period of time." But as Perkins well understands, there is a difference between the "mission perspective" and the historical and social value of these particular tapes. The missing videos could help excite a new generation about exploring space, and they offer significant commercial possibilities as well. "Maybe somebody didn't have the wisdom to realize that the original tapes might be valuable sometime in the future," she said. "Certainly, we can look back now and wonder why we didn't have better foresight about this." |