|

|

|||||

|

..

Last

Updated: October 13, 2002

Not likely! The explosion

of a nuclear weapon on the moon would be visible

The first idea of exploding a bomb on the lunar surface seems to be in Robert Goddard's "A Method for reaching extreme altitudes". Goddard investigated the possibility of reaching the Moon with a rocket loaded with photographer magnesium powder, in order to record the explosion made by the impact. Instead of carrying out a simple theoretical study, in October 1916 Goddard made an experiment to establish the minimum powder mass to be carried by the rocket. By observing at night from his Worcester home the magnesium flash made in an air evacuated glass ampule located some 3,600 meters away, he determined that the flash made by 0.0029 grams of magnesium was barely visible and the one made by 0.015 grams was plainly so. From these data he calculated that, using a 30 cm diameter telescope to observe the impact, the rocket was to carry 1.2 kg of magnesium for the flash to be barely visible and 6.27 kg to be plainly so. To carry this mass to the moon, Goddard estimated that it was necessary to use a rocket of some fifteen tons launch mass, able to accelerate the payload to escape speed. Goddard himself noted that "the plan of sending a mass of flash powder to the surface of the moon, although a matter of much general interest, is not of obvious scientific importance". This was however the first idea of an interplanetary mission to do without of the presence of humans: the first "space probe". Later, in the Forties, the German born popular science writer Willy Ley further perfected the Goddard idea. He noted in fact that if the terrestrial observers able to observe the lunar impact of the magnesium laden probe were incapacitated by bad weather, the impact may happen without any witness. To counter this problem Ley proposed the impact on the Moon of 0.5 kg of high explosive and 4.5 kg of white powder, possibly powdered glass that, once dispersed on the surface, would have formed a patch of surface more brilliant than the surroundings. In 1945 US astronomer H. H. Nininger suggested the

use of two new technologies developed during the most recent war, guided

missiles and atomic weapons, to dislodge lunar soil samples and to carry

them toward the Earth, thus providing an artificial imitation of what astronomers

believed had happened during the formation of the larger craters or during

the eruption of the lunar volcanoes, creating a class of natural glasses

called tektites.

In October of the same year, JPL (Jet Propulsion Laboratory) presented its idea of a lunar program that would overshadow Sputnik. The program was called Red Socks and it could include the detonation of an atom bomb on our natural satellite's surface, in order to collect, as Nininger had proposed, any lunar rock that would be hurled to our planet by the explosion and to produce, in the words of JPL's director Pickering to produce "beneficial psychological results". As the first race to the Moon unfolded, both the USA and the USSR had plans to nuke the Moon. In parallel with the Able

probes' development, the US Air Force started

a top secret project, called A119, described euphemistically as a "study

of lunar research flights" and only revealed 42 years after its conception.

However, such a project would probably have been forgotten had the Soviet Union not declared an unilateral nuclear test ban on March 31, 1958. This ban was interrputed on September 30, announced by the United States on October 31 and finally accepted by the Soviet Union in December. The ban was supposed to lead to a total test ban but, for lack of an agreement, the Soviet Union resumed testing on September 1, 1960, followed by the United States four days later. Despite this, for almost two years the two superpowers did not explode a single nuclear weapon. In this climate of incertitude, it is not surprizing that the US military considered moving their own tests in space, giving them an aura of scientific respectabily. Project A119 was thus started by the US Air Force Special (i.e. nuclear) Weapons Center, its main aim being of sending to the Moon without any warning a fission atomic bomb to impress the Soviets and their allies. Very few details of the project have been revealed, and the few ones mostly concern the scientific side. To the project in fact participated from the spring of 1958 a small group of scientists of the Armour Research Fondation of the Illinois Institute of Technology, providing scientifical consultancy on the mission. This group included many well known scientists such as Leonard Reiffel, project chief scientist and later to be the manned Apollo lunar missions scientific instrumentation manager, Gerard P. Kuiper, a Dutch born planetlogist and his doctorate student Carl Sagan, the future famous planetary astronomer, scientist popularizer and author of the science fiction novel Contact. Counting on the accuracy of the launcher, far too optimistically estimated as "a couple of miles" at the Moon's distance, it was decided to explode the bomb on the night side close to the terminator, in order to maximize visiblity. Whatever the yield of the bomb and contrary to Kuiper's calculations, the crater created by the explosion would not have been visible: a 1 kiloton bomb would have digged a 50 meters diameter crater and a 1 megaton a less than 400 meters diameter one. In contrast to the similar Soviet project of which more later, the American project never reached the mission hardware stage. We thus ignore the chosen launcher, probably an uprated version of the Atlas or Titan ICBM and the characteristics of the bomb. The final scientific report on the mission, signed by Reiffel and recently made public through the Freedom Of Information Act, envisages the possibility of usign weapons yelding as much as a megaton (one million tons of TNT) but the most probable choice, because of mass limitations, would have been a bomb at least as powerful as the one dropped on Hiroshima (some twenty kilotons). Although the aim of the mission was a different one, the report describes the possible scientific fallout of the lunar explosion, mainly relating to the possiblity of studying the thermal characteristics of the surface exposed to the explosion's heat, of collecting data on the internal structure of the Moon and particularly on the existence of a metallic nucleus, if one to three seismometers had been placed on the surface in anticipation of the explosion, of studying the rock composition and the presence of a magnetic field. Other scientific investigations related to the project were carried out by Sagan but we only know the titles of these: "Possible Contribution of Lunar Nuclear Weapons Detonations to the Solution of Some Problems in Planetary Astronomy" and "Radiological Contamination of the Moon by Nuclear Weapons Detonations". This second paper, in particular, dealt with the effects of radioactive fallout on the surface of the Moon, which could have altered Lunar geology research for centuries to come. Of course the military were not at all concerned by this problem. However, Reiffel himself was skeptical in his report of the opportunity of staging such a mission, noting that the reaction of the unprepared public opinion to the explosion of an atom bomb on the Moon would have probably been negative. As the mission was mainly designed as a public relations exercise, it is not surprising that the project was terminated in January 1959. Alas, many documents on project A119 were destroyed during the Eighties by the Illinois Institute of Technology and it is thus unlikely that other informations may surface in the future. The Soviet project was called E-4 and was to detonate an atom bomb on the visible hemisphere to provide a dramatic visual confirmation of the impact and to perform a remote chemical analysis of the soil vaporized in the explosion.. The probe weighted 400 kg and its shape was similar to an E-1 (flown as Luna-1 and Luna-2) with detonators protruding like an anti-ship mine. The yield of the weapon is not known, but it was probably quite small, considering the weight of the probe and the Soviet state of the art (for example, the RDS-4 Natasha tactical atom bomb, which entered service in 1953, yielded 30 kTons and weighted, in its air dropped version, 1200 kg). In fact, it is unlikely that the probe would have had the time to explode, since it would have hit the Moon traveling at a speed (3 km/s) close to the "speed of information" (i.e. the speed of sound) in the metal detonating system. The launcher was to be an 8K73, a uprated version of

the 8K72 that

launched Luna-1, Luna-2 and Luna-3.

Second, it was also discovered that, there being no

lunar atmosphere to form the characteristic "mushroom shaped" cloud, a

nuclear or conventional explosion on the Moon would have been visible only

as a very brief flash of light and possibly a small dust cloud. One can

again consider the case of the US Dominic nuclear test of October 20, 1962,

when a 60 kTon bomb was detonated in the highest regions of the atmosphere,

at an height of 147 km. According to eye witnesses, no fireball was visible,

but instead a circular blue region inside a blood red ring was seen, and

it disappeared in less than a minute.

(C) Paolo Ulivi. Made with Catia 4.2.2 The Partial Test Ban Treaty, which prohibited any nuclear

explosion on the atmosphere or into space, entered in force in 1963 and

four years later the Treaty

on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and

Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and other Celestial Bodies,

which prohibited the stationing of nuclear weapons in space, closed forever

the page of the nuclear space probes. Before 1963, however, the US exploded

six bombs into space and the USSR four more. As late as the Seventies,

the Soviets were however still planning to explode a nuclear bomb on the

surface of Venus to calibrate seismic models of the planet.

The information was obviously false, but the project was not. Some images from Operation Dominic

Technicians in radiation suits inspect the engine of the nuclear tipped Thor missile that failed on the pad at Johnston Island on July 25, 1962. Parts of the pad had radiation counts as high as 1,000,000 CPM (Counts Per Minute), hundred thousands times higher than ambient radiation.

A still from a DOE Operation Dominic movie. This is probably the Fishbowl Bluegill Triple Prime explosion of October 26, 1962.This was a megaton range Thor airbust at an height of some 49 km.A toroidal cloud is seen to be forming.

Another DOE movie still.This is probably the November 1 burst of a Thor launched 200 to 400 kT warhead which detonated at an height of 96 km (i.e. above the atmosphere) The explosion appeared as a bright yellow glow whose long axis reached 125 miles after 30 minutes, and eventually reached 185 miles. This glow persisted for at least 1.5 hours. Bibliography:

|

|||||

| Treaty on Principles Governing

the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including

the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies

U.S. Department of State

|

|||||

|

US planned one big nuclear blast for mankind ..

In an exclusive interview with The Observer, Dr Leonard Reiffel, 73, the physicist who fronted the project in the late Fifties at the US military-backed Armour Research Foundation, revealed America's extraordinary lunar plan. 'It was clear the main aim of the proposed detonation was a PR exercise and a show of one-upmanship. The Air Force wanted a mushroom cloud so large it would be visible on earth,' he said yesterday. 'The US was lagging behind in the space race.' 'The explosion would obviously be best on the dark side of the moon and the theory was that if the bomb exploded on the edge of the moon, the mushroom cloud would be illuminated by the sun.' The bomb would have been at least as large as the one used on Hiroshima at the end of World War II. 'I made it clear at the time there would be a huge cost to science of destroying a pristine lunar environment, but the US Air Force were mainly concerned about how the nuclear explosion would play on earth,' said Reiffel. Although he believes the blast would have had little environmental impact on Earth, its crater may have ruined the face of the 'man in the moon'. Reiffel would not reveal how the explosion would have taken place. But he confirmed it was 'certainly technically feasible' and that at the time an intercontinental ballistic nuclear missile would have been capable of hitting a target on the moon with an accuracy of within two miles. Reiffel was approached by senior US Air Force officers in 1958, who asked him to 'fast-track' a project to investigate the visibility and effects of a nuclear explosion on the moon. The top-secret Project A119, was entitled 'A Study of Lunar Research Flights'. 'Had the project been made public there would have been an outcry,' said Reiffel. Many Cold War documents are still classified in the US, but details of Project A119 emerged after a biography of celebrated US scientist and astronomer Carl Sagan was published there last year. Sagan, who died in 1996, was famous for popularising science in the US and pioneering the study of potential life on other planets. At the Armour Foundation in Chicago - now called the Illinois Institute of Technology Research - he was hired by Reiffel to undertake mathematical modelling on the expansion of an exploding dust cloud in the space around the moon. This was key to calculating the visibility of such a cloud from the Earth. At the time scientists still believed there might be microbial life on the moon and Sagan had suggested a nuclear explosion might be used to detect organisms. Despite the highly classified nature of the work, Sagan's biographer, Keay Davidson, discovered that he had disclosed details of it when he applied for the prestigious Miller Institute graduate fellowship to Berkeley. Yet, until today, the full nature of Project A119 has never been revealed. Friends of Sagan believe he never would have wilfully revealed classified information, but Reiffel has come forward to put the 'historical record straight'. Reiffel continued: 'It was well known that the existence of this project was top secret. Had Sagan wanted to make any disclosures to any party, as his boss at the time, I would have had to take forward any such request and Air Force permission would have been extremely unlikely in those very tense times.' In a letter to the science magazine Nature, Reiffel said: 'Fortunately for the future of lunar science, a one or two horse race to detonate a nuclear explosion never occurred. But in my opinion Sagan breached security in March, 1959.' Reiffel produced eight reports between May 1958 and January 1959 on the feasibility of the plan, all of which were destroyed in 1987 by the foundation. Reiffel would not discuss details of these reports, believing they were still classified, but it was clear the conclusion was that the explosion would have been visible from Earth He does not know why the plans were scrapped, but said: 'Thankfully, the thinking changed. I am horrified that such a gesture to sway public opinion was ever considered.' Dr David Lowry, a British nuclear historian, said: 'It is obscene. To think that the first contact human beings would have had with another world would have been to explode a nuclear bomb. Had they gone ahead, we would never have had the romantic image of Neil Armstrong taking "one giant step for mankind".' Lowry believes Project A119 has relevance today with the US proposing a missile defence system in space. He said: 'The US has always wanted to militarise space and some of the fanciful ideas currently being put forward will seem as incredible as the idea of nuking the moon in the Fifties seems today.' A Pentagon spokesman would not confirm or deny the plans. This article appeared in the Observer

on Sunday May 14 2000

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2008 |

|||||

|

Under a Cloud The Observer, Sunday May 21, 2000 Re 'US planned one big nuclear blast for mankind' (News, last week). This foolish experiment may have produced some sort of cloud but it would not have been remotely mushroom-like (unless one quibbles and includes pufballs as mushrooms). Mushroom clouds are a phenomenon caused by convection, which requires an atmosphere. So far as I am aware, the moon lacks an atmosphere, although we only have Nasa's word on that. S. A. Minns

|

|||||

|

A Study of Lunar Research Flights Volume 2 As detailed elsewhere on this website, during 1958 and 1959 the US Air Force studied project A119 which called for the explosion of a nuclear weapon on the surface of the Moon. This project remained secret until 2000, when Leonard Reiffel, a former scientist of the Illinois Institute of Technology revealed its existence. One report (AFSWC TR-59-39) was produced by the Armour Research Foundation of the Illinois Institute of Technology on the scientific aspects of the project, and I was able to obtain its first volume from the Kirtland AFB FOIA office. This volume is now available in PDF

version by clicking on the cover at left. (NOTE: the second volume

is apparently unavailable either from Kirtland

AFB and the Illinois Institute of Technology)

In fact, the report reveals very little on the A119 project and the main reason of its interest is that it provides an overview of lunar science at the very early days of lunar exploration. Some parts make for a good reading even today. Chapter IV in particular, details the knowledge to be gained from seismic studies on the surface on the Moon. Chapter VIII, on the possible presence of organic matter on the Moon, betrays the association of a young Carl Sagan with the project. As a final remark, it is worth noting that the report does not carry any "secret" marking! |

|||||

|

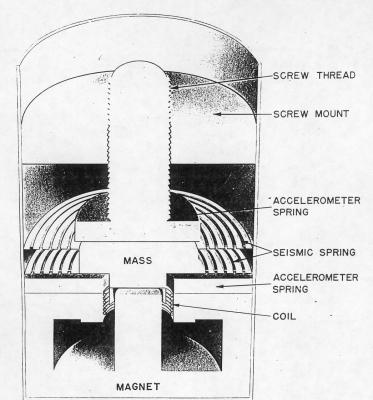

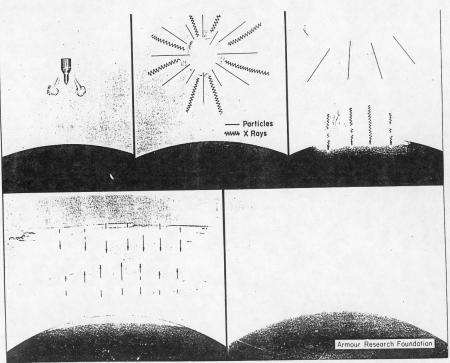

Two images from the Reiffel report: ..

..

|

|||||

|

One Nuclear Bomb For Moon, One Big Blast For Humanity ..

LONDON (AFP) - The United States drew up a secret plan to detonate a nuclear bomb on the face of the moon as a display of military muscle at the height of the Cold War, Britain's Observer reported late Saturday. Leonard Reiffel, the physicist who fronted the project, told the Sunday weekly in an interview that the scheme, hatched in the late 1950s, was as a public relations stunt. "It was clear the main aim of the proposed detonation was a PR exercise and a show of one-upmanship," he said. "The Air Force wanted a mushroom cloud so large it would be visible on earth. The US was lagging behind in the space race." He said the blast would have been on the dark side of the moon, "and the theory was that if the bomb exploded on the edge of the moon, the mushroom cloud would be illuminated by the sun." Reiffel said he did not think a nuclear explosion on the moon would have had a major environmental effect on Earth, although it would have ruined the face of the moon. "I made it clear at the time there would be a huge cost to science of destroying a pristine lunar environment," he went on, "but the US Air Force were mainly concerned about how the nuclear explosion would play on Earth." Reiffel, now 73, would not tell the Observer how the bomb would have been detonated, only that it was "certainly technically feasible." At that time, he said, an intercontinental ballistic nuclear missile would have been capable of hitting a target on the moon with an accuracy of within two miles. "Had the project been made public there would have been an outcry," the scientist acknowledged. But it was not. He said the scheme, known as Project A119, was entitled "A study of lunar research flights" and was based at the US military-backed Armour Research Foundation in Chicago - now renamed the Illinois Institute of Technology Research. Reiffel produced eight reports between May 1958 and January 1959 on the feasibility of the plan. The documents were destroyed by the Foundation in 1987. "Thankfully the thinking changed," he said. "I am horrified that such a gesture to sway public opinion was ever considered." The bomb would have been at least as large as the one that destroyed Hiroshima to bring World War II to a close SOURCE: Islam Online |

|||||

|

Sagan breached security by revealing US work on a lunar bomb project Leonard Reiffel 1. Exelar Corporation, 602 Deming Place , Chicago, Illinois 60614, USA In his review of two biographies of Carl Sagan, by William Poundstone and by Keay Davidson (Nature 401, 857 ; 1999), Christopher Chyba deals extensively with "Davidson's accusation that the young Sagan wilfully and illegally revealed classified information..." and further states: "This is a serious and specific legal allegation which Davidson does not substantiate". The classified project involved, Project A119, entitled A Study of Lunar Research Flights (SECRET), was conducted at Armour Research Foundation (ARF) while I was manager of physics research. |

|||||

| FAIR USE NOTICE: This page contains copyrighted material the use of which has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. Pegasus Research Consortium distributes this material without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. We believe this constitutes a fair use of any such copyrighted material as provided for in 17 U.S.C § 107. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond fair use, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. | |||||

|

|