Geminid Meteor Shower Defies

Explanation

Dec. 6,

2010:

The Geminid

meteor shower, which peaks this year on Dec.

13th and 14th, is the most intense meteor shower

of the year. It lasts for days, is rich in

fireballs, and can be seen from almost any point

on Earth.

"It was a

monster fireball," says photographer Wally

Pacholka. "I caught it exploding over the

Hercules Finger rock formation near Victorville,

California, using a Canon 35 mm camera. This was

one of 1522 photographs I took "

The fireball occurred during the Geminid meteor

shower, which peaked on Dec. 13th and 14th when

Earth passed through a stream of debris from

3200 Phaethon. In some places, people saw 200+

Geminids per hour. In the Mojave desert, one was

enough!

It's also NASA

astronomer Bill Cooke's favorite meteor

shower—but not for any of the reasons listed

above.

"The Geminids

are my favorite," he explains, "because they

defy explanation."

Most meteor

showers come from comets, which spew ample

meteoroids for a night of 'shooting stars.' The

Geminids are different. The parent is not a

comet but a weird rocky object named 3200

Phaethon that sheds very little dusty debris—not

nearly enough to explain the Geminids.

"Of all the

debris streams Earth passes through every year,

the Geminids' is by far the most massive," says

Cooke. "When we add up the amount of dust in the

Geminid stream, it outweighs other streams by

factors of 5 to 500."

This makes the

Geminids the 900-lb gorilla of meteor showers.

Yet 3200 Phaethon is more of a 98-lb weakling.

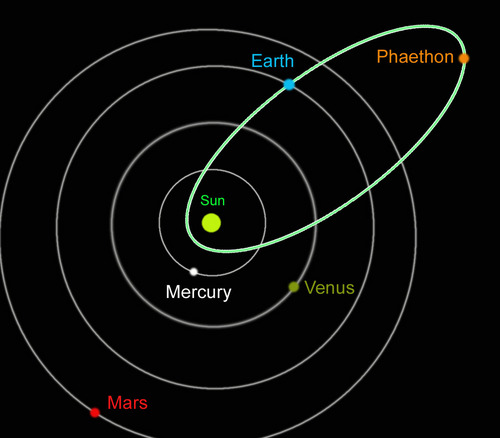

3200 Phaethon

was discovered in 1983 by NASA's IRAS satellite

and promptly classified as an asteroid. What

else could it be? It did not have a tail; its

orbit intersected the main asteroid belt; and

its colors strongly resembled that of other

asteroids. Indeed, 3200 Phaethon resembles main

belt asteroid Pallas so much, it might be a

5-kilometer chip off that 544 km block.

..

Credit:

An artist's concept of an impact event on

Pallas. Credit: B. E. Schmidt and S. C.

Radcliffe of UCLA.

"If 3200 Phaethon broke apart

from asteroid Pallas, as some researchers

believe, then Geminid meteoroids might be debris

from the breakup," speculates Cooke. "But that

doesn't agree with other things we know."

Researchers have looked

carefully at the orbits of Geminid meteoroids

and concluded that they were ejected from 3200

Phaethon when Phaethon was close to the sun—not

when it was out in the asteroid belt breaking up

with Pallas. The eccentric orbit of 3200

Phaethon brings it well inside the orbit of

Mercury every 1.4 years. The rocky body thus

receives a regular blast of solar heating that

might boil jets of dust into the Geminid stream.

Could this

be the answer?

..

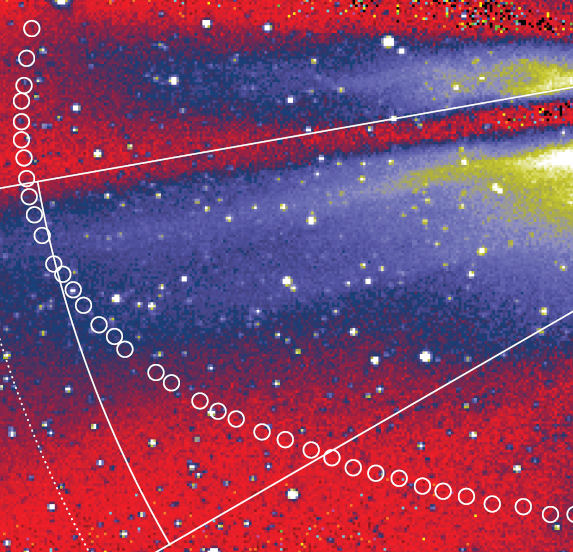

The path

of 3200 Phaethon through STEREO's HI-1A

coronagraph camera. False-color green and blue

streamers come from the sun.

To test the

hypothesis, researchers turned to NASA's twin

STEREO spacecraft, which are designed to study

solar activity. Coronagraphs onboard STEREO can

detect sungrazing asteroids and comets, and in

June 2009 they detected 3200 Phaethon only 15

solar diameters from the sun's surface.

What happened

next surprised UCLA planetary scientists David

Jewitt and Jing Li, who analyzed the data. "3200

Phaethon unexpectedly brightened by a factor of

two," they wrote. "The most likely explanation

is that Phaethon ejected dust, perhaps in

response to a break-down of surface rocks

(through thermal fracture and decomposition

cracking of hydrated minerals) in the intense

heat of the Sun."

Jewett and Li's

"rock comet" hypothesis is compelling, but they

point out a problem: The amount of dust 3200

Phaethon ejected during its 2009 sun-encounter

added a mere 0.01% to the mass of the Geminid

debris stream—not nearly enough to keep the

stream replenished over time. Perhaps the rock

comet was more active in the past …?

"We just don't

know," says Cooke. "Every new thing we learn

about the Geminids seems to deepen the mystery."

This month Earth

will pass through the Geminid debris stream,

producing as many as 120 meteors per hour over

dark-sky sites. The best time to look is

probably between local midnight and sunrise on

Tuesday, Dec. 14th, when the Moon is low and the

constellation Gemini is high overhead, spitting

bright Geminids across a sparkling starry sky.

Bundle up, go outside, and savor

the mystery.

Author: Dr.

Tony

Phillips | Credit: Science@NASA

SOURCE: NASA

SCIENCE